The Underestimated Risk of Deflation in America

Author: Chris Wood

If Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell signaled the commencement of monetary easing in his 23 August speech at Jackson Hole, more interesting to this writer from a more historical perspective was his total failure again to acknowledge that the huge expansion in broad money supply growth in the spring of 2020 was the main cause of America’s subsequent surge in inflation.

This is truly remarkable since, as this writer can report having talked to many investors in the past four years, most of them believe that the 26.7% rise in M2 in the 12 months to February 2021 was the main trigger for the inflation.

Indeed, it raises the question of whether Powell himself really believes the official line, as well as the rest of the Fed and its more than 400 PhD economists.

Unfortunately, it is probably the case that many of them do believe it, though, in the case of Powell, it should be assumed that he must have some real doubts, as he was clearly given the wrong advice at the time in terms of the transitory inflation thesis.

Indeed, he noted in his Jackson Hole speech that “standard thinking” has long been that, as long as inflation expectations remain “well anchored”, it is appropriate to look through a temporary rise in inflation.

If this was the case for believing the inflation would be “transitory”, the Fed chairman also noted that “the good ship Transitory was a crowded one, with most mainstream analysts and advanced economy central bankers on board”.

Still, as he also noted, from October 2021 the data turned “hard against the transitory hypothesis” and the Fed commenced the biggest tightening cycle since the early 1980s from March 2022.

The Fed is Still Talking About Inflation, It Should be Focused on Deflation Instead

If that is the history, Powell is now seemingly confident that inflation is under control.

He is also relieved that long-term inflation expectations have remained under control throughout the whole tightening cycle, given that, as he rightly notes, it was far from assured that the “inflation anchor” would hold.

On that point, it is indeed the case that five-year five-year forward inflation expectations peaked at 2.67% in April 2022 and have been in a relatively tight range of 2.08% to 2.53% since May 2022 throughout this tightening cycle.

Powell also observed that an “important takeaway” from the recent experience is that anchored inflation expectations can facilitate disinflation “without the need for slack”, by which he presumably means high unemployment and other classic symptoms of a recession.

If that is Powell’s analysis of this cycle, and it is entirely understandable that the Fed chairman takes comfort from the American economy’s continuing remarkable resilience in the face of 525bp of monetary tightening, this writer remains somewhat bemused by the extreme focus on inflation expectations and the complete lack of focus on what is happening to the monetary aggregates.

On that point, there still remains a risk that the American economy has not yet felt the full impact of the decline in broad money supply growth which has been under way since March 2021 because of the huge base effect stemming from the M2 explosion in 2020.

M2 growth has declined from a peak of 26.7% YoY in February 2021 to a negative 4.5% YoY in April 2023 and has since risen to 2.0% YoY growth in August.

On an absolute basis, US M2 surged by US$6.29tn or 41% from US$15.43tn in February 2020 to the peak of US$21.72tn in April 2022. It has since declined by US$1.03tn or 4.8% to a recent low of US$20.69tn in October 2023 before rising to US$21.17tn in August.

How Does Japan Compare?

Meanwhile, monetary aggregates are also relevant in the case of Japan.

This writer has long favoured a normalisation of Japanese monetary policy, primarily because negative rates are negative in themselves, creating perverse incentives.

It also remains the case that 1% is a more appropriate inflation target for Japan than 2% and that inflation rate has long since been reached.

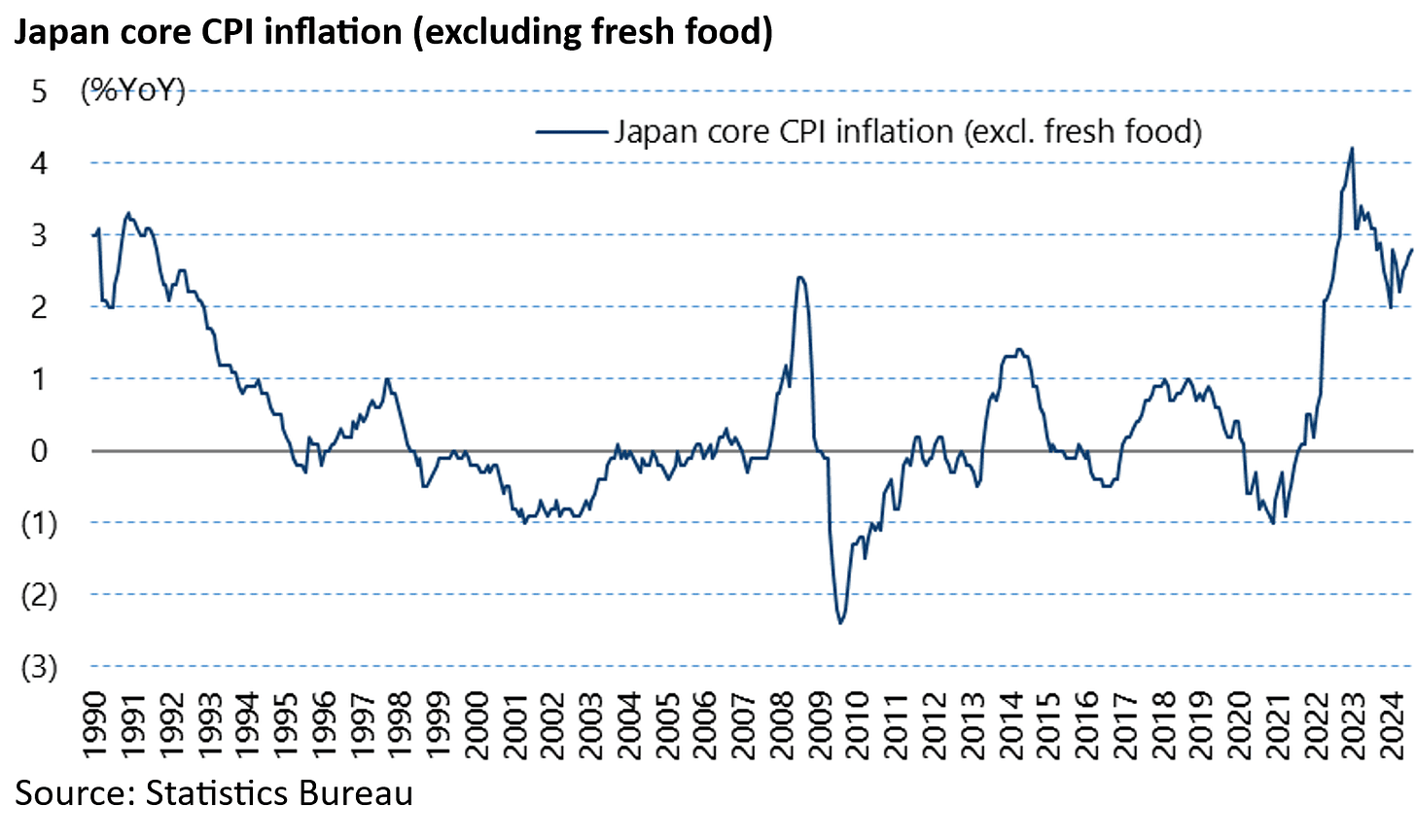

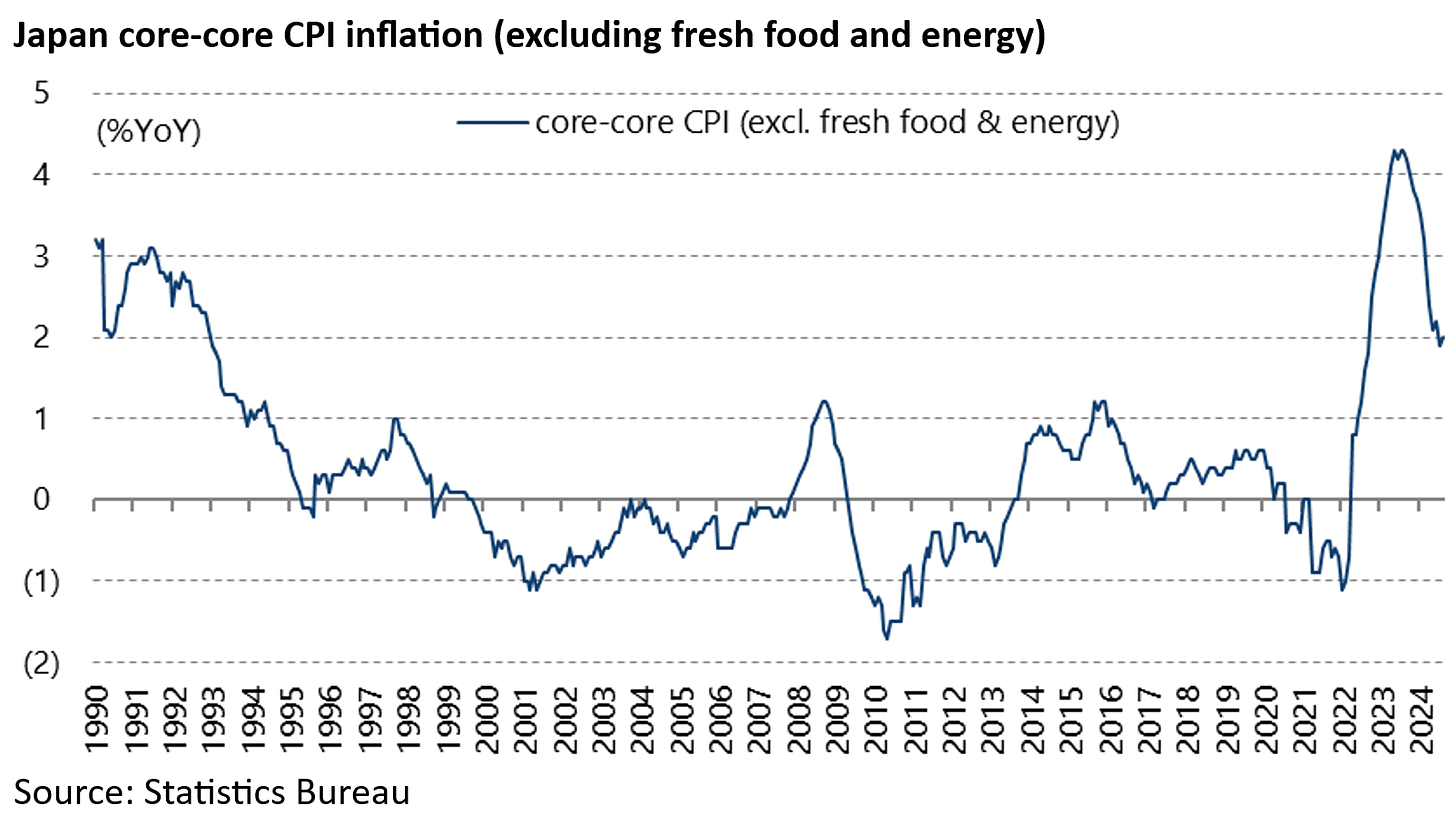

Japan core CPI inflation, which excludes fresh food but includes energy, has been above 1% (also 2%) since April 2022.

As for CPI inflation excluding fresh food and energy, it rose to 1.0% YoY in June 2022 and was 2.0% YoY in August in terms of the latest data.

Still, it should also be acknowledged that, from a more narrowly focused monetary policy standpoint, the case that Japan is out of deflation looks much less clear-cut.

In this respect, unlike most of the rest of Asia, there was a marked pickup in M2 growth in Japan in 2020, triggered by pandemic-related policies.

Indeed, Japan M2 growth peaked at 9.6% YoY in February 2021.

While this was well below the level of broad money growth in the US, it was the highest level of broad money supply growth in Japan since November 1990.

Indeed, M2 growth has averaged only 2.6% between 1991 and 2019 during the post Bubble Economy era.

In this respect, the surge in Japan’s inflation post pandemic has a monetary explanation.

But the subsequent decline in M2 growth since creates a deflationary risk, albeit with a pronounced time lag, just as it does in the US. Japan M2 growth has slowed to 1.3% YoY in August, the lowest level since April 2007.

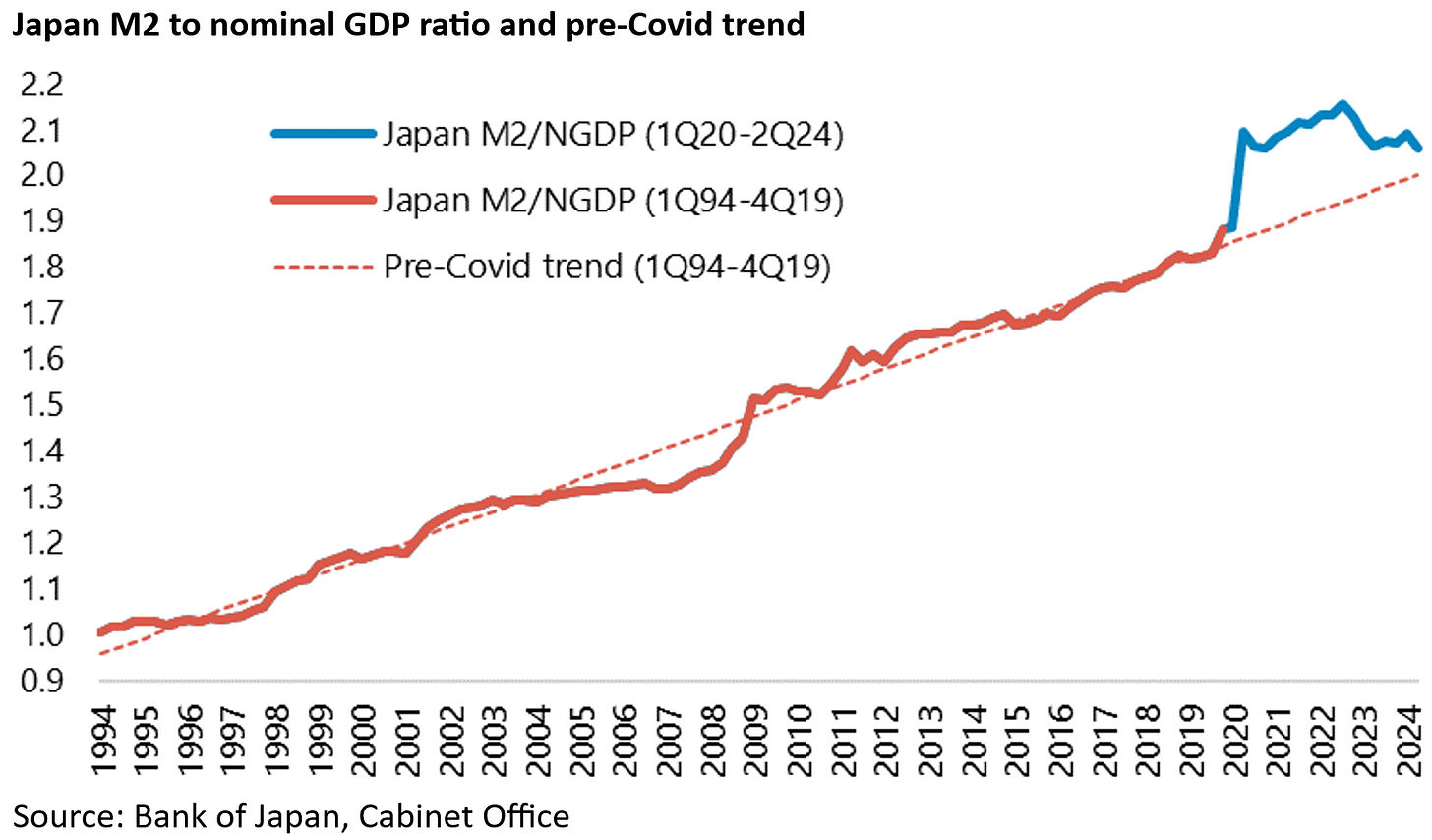

As discussed here previously in terms of a similar methodology applied to America, the Japan M2 to nominal GDP ratio rose from the pre-Covid level of 1.884 in 4Q19 to 2.096 in 2Q20 or 12.4% above the pre-Covid trend line between 1994 and 2019.

It has since risen further to a peak of 2.157 in 3Q22 or 11.1% above the pre-Covid trend.

The ratio remains 2.059 in 2Q24 or 2.8% above the pre-Covid trend.

By contrast, America’s M2 to nominal GDP ratio has now declined to 4.0% below its pre-Covid trend line in 2Q24, down from 25.7% above trend in 2Q20.

Meanwhile, like the Fed, the BoJ is not really talking about the monetary aggregates.

But the reality is that the hurdle for it to raise rates again has increased significantly as a consequence of the recent yen carry trade-triggered bout of risk aversion in late July, as discussed here previously (see Is More Carry Trade Volatility In Store For Markets?, 18 September 2024).