With Bank Lending on the Decline, Why Aren't We in a Recession Already?

Author: Chris Wood

The action in Big Tech stocks has continued to be amazingly resilient, helped by the AI story, positive cash flow generation and the fact that these are global plays with an average 55% of their revenues derived from outside America.

Never mind that earnings multiples look very high.

For example, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft and Nvidia are trading on 29x, 34x, 31x and 26x 12-month forward earnings.

It is also the case that US Big Tech stocks’ share of S&P500 market capitalisation, with Nvidia now included, recently surpassed the previous peak of 27.3% reached in September 2020.

It rose to 28.7% on 10 November and is now 27.6%

By contrast, a chart of US bank stocks, a classic domestically orientated cyclical sector, looks less healthy despite the recent euphoric rally.

Falling Bank Loan Growth Is Still a Red Flag for the Economy

If one lingering concern is the losses on the Treasury bond holdings discussed here before (see A Treasury Maturity Wall Is Coming, Is Your Portfolio Ready?, 1 November 2023), the more relevant issue is the rising recession risk as reflected in the sharp decline in loan growth.

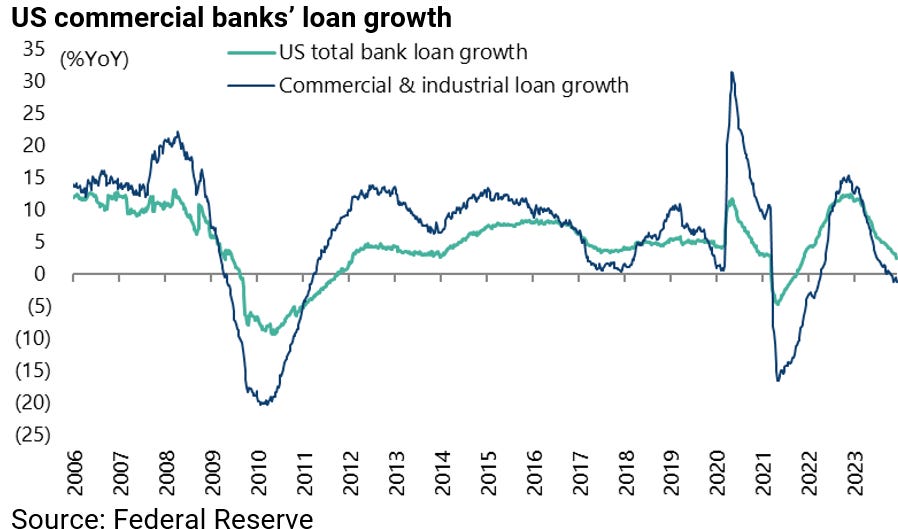

Commercial banks’ total loan growth has slowed from US$1.33tn or 12.5% YoY in early December 2022 to US$287bn or 2.4% YoY in the week ended 6 December, while commercial and industrial (C&I) loan growth has collapsed from US$373bn or 15.3% YoY in late November 2022 to a US$34.5bn or 1.2% YoY decline.

Declining bank loan growth is a classic indicator of rising recession risks, as is a tightening in loan standards, be it a decline in banks’ willingness to lend or borrowers’, be they corporates or consumers, willingness to borrow.

Still, the interesting issue right now is that the traditional correlation between a proxy of lending standards and borrowing standards, based on the Federal Reserve Senior Loan Officer Survey, and US real GDP growth has, for now at least, broken down as can be seen clearly in the chart below.

The question is, has the correlation broken down completely, or is there another area of credit extension, not captured in the central bank’s survey, which is keeping the credit extension cycle game going for now at least?

The answer is that there is one area of credit extension which, by all accounts, still seems to be booming.

And that is private credit, which appears to be the hot asset class right now.

Private Credit is Keeping the Bull Market Going, Even with Bank Lending on the Decline

An interesting article in the Wall Street Journal recently reported that a “handful” of fund managers control about US$1tn out of the private credit assets globally which totalled US$1.5tn at the end of 2022, accounting to date provider Preqin (see Wall Street Journal article: “The New Kings of Wall Street Aren’t Banks. Private Funds Fuel Corporate America”, 8 October 2023).

The interesting macro point is to what extent the seemingly still booming world of private credit area is further delaying the lagged impact of monetary tightening, since that monetary tightening is having an impact is clear from commercial banks’ declining loan growth.

This cannot be quantified precisely but it is definitely having some impact, since money invested in private credit is still growing, while commercial and industrial (C&I) loans have stopped growing, as already mentioned.

On this point, Preqin data shows that private-credit assets under management globally doubled from US$725bn at the end of 2018 to US$1.46tn at the end of 2022 and were up another 10% or US$141bn to US$1.61tn at the end of 1Q23, the latest data available.

By contrast, US commercial banks’ C&I loans outstanding rose from US$2.3tn at the end of 2018 to US$2.81tn at the end of 2022 but were down 1.3% or US$37bn in the first 11 months of this year to US$2.77tn in November.

Private Credit Bubbles Will be Larger and Far Worse than Public Ones

If the delayed impact of monetary tightening is one issue, another issue relating to private credit was discussed in some detail in a recommended Moody’s report published in September ((see Moody’s report: “Private Credit – Global: Syndicated and private lenders will spar as LBOs revive, upping systemic risk”, 28 September 2023).

The report detailed how private lenders have built up a “considerable arsenal of dry powder”, totalling nearly US$214bn in the case of direct lending funds.

This means they will need to keep lending to meet their commitments to their limited partners.

Moody’s worry is that the growing “frenzy” to lend and the related lack of visibility, in contrast with the banks, will “make it difficult to see where risk bubbles may be building… and could have repercussions for the broader economy”.

Moody’s also goes on to highlight the development of what it describes as “an ever-expanding, interrelated lending and investing loop”.

This writer will quote the next sentence from the report verbatim since it goes to the heart of the matter. “In this loop, alternative asset managers become investors in private credit, which supports private equity deals.

Private equity sponsors, which used to go to banks, are increasingly partnering with private credit entities or starting their own private credit arms to source capital.”

The above points highlight again that this is a credit cycle with its own specific features.

Certainly, the booming ‘’private’’ world of alternatives has become big enough, in the context of the American economy and its financial system, that it has now become of macro relevance, as illustrated by the abovementioned Moody’s report.

While all this activity can extend the cycle, it does not mean that there will not be a cycle.

Indeed, the damage will likely be all the greater because the credit excesses will be that much greater, in terms of bad loans made at the peak of the cycle—though the collateral damage will extend well beyond banks, with insurance companies one obvious area of vulnerability.

On that point, the abovementioned Moody’s report also noted that private credit asset managers are increasingly buying up or affiliating with insurance companies in order to obtain “direct access to long-term capital that they can deploy through their lending arms”.