Will China Allow the US Style Housing Bailout It Desperately Needs?

Author: Chris Wood

Higher for longer has undoubtedly been the consensus among investors in recent months.

Money markets have repriced when rate cuts are meant to commence with the timeline now pushed back to June, June and September next year in the cases of America, Eurozone and Britain.

Indeed as regards the Fed and the Bank of England, money markets are still discounting a 38% chance of one more 25bp rate hike by the Fed by January 2024 and a 45% chance of another 25bp rate hike by the BoE by February.

As for the data dependent Fed, the next key data point is September core PCE inflation to be announced on 27 October.

The consensus expects 3.7% YoY, down from 3.9% in August, primarily as a consequence of the base effect.

The above means equity markets still face significant competition from a risk-free rate of 5.3% in the case of the US.

Gold is Showing Suprising Resiliance

This context, combined with a spike in the 10-year Treasury bond yield to 5.02% on Monday, or its highest level since July 2007, should mean rising pressure on gold.

Still gold is down only 4.2% from its 2023 peak of US$2,063/oz reached on 4 May.

This writer remains impressed by the relative resilience of gold now, and indeed throughout this current Fed tightening cycle.

One key reason for this, as previously discussed here (see Gold is back, Next stop $6,000?, 22 March 2023), has been increased central bank buying of gold since the freezing of some US$300bn of Russia’s foreign exchange reserves in late February 2022.

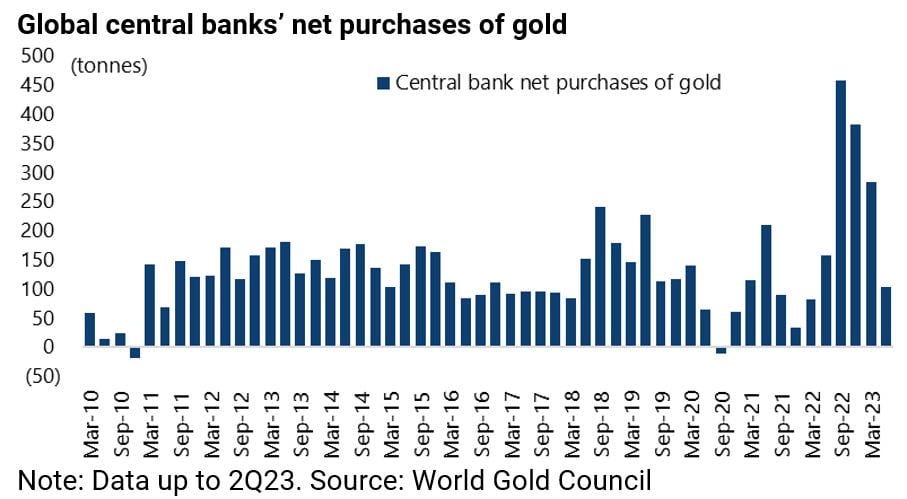

Still it is worth noting that the pace of central bank buying of gold slowed in 2Q23 based on the latest World Gold Council data.

Thus, central banks bought a net 102.9 tonnes in 2Q23, down from 284 tonnes in 1Q23 and a peak of 458.8 tonnes in 3Q22.

As a result, they bought a record 1,081.6 tonnes last year and 386.9 tonnes in 1H23.

We See Early Signs of Stabilization in Chinese Housing, But too Early to Call an All Clear

Meanwhile, the Asia focused news flow has remained primarily on China where concerns about inflation remain conspicuous by their absence.

China CPI inflation was 0.0% YoY in September while core CPI inflation was 0.8% YoY.

It is now eight weeks since China announced the most significant of its various incremental easing measures undertaken this year, namely lowering on 31 August the downpayment requirements on mortgages nationwide to 20% for first-time homebuyers and 30% for second-home buyers, down from 30-40% for first-home buyers and 50-80% for second homes in tier-1 cities.

The initial evidence, though it is still early days, is that there are some signs of a stabilisation in property sales; though this writer would not want to exaggerate this.

It is also the case that the one-week national holiday in the first week of October also impacts the data.

This is traditionally a week which sees a downturn in property transactions.

But given the downturn in the market which preceded it, this writer would view a stabilisation in activity as a positive not a negative.

On this point, weekly primary residential floor space sales in the major 30 cities averaged 2.345m sqm in the four weeks ended 15 October, up 9% from the previous four weeks and were 18% above the recent low of 1.988m sqm in the four weeks to 27 August prior to the announcement, though they are still down 21% YoY.

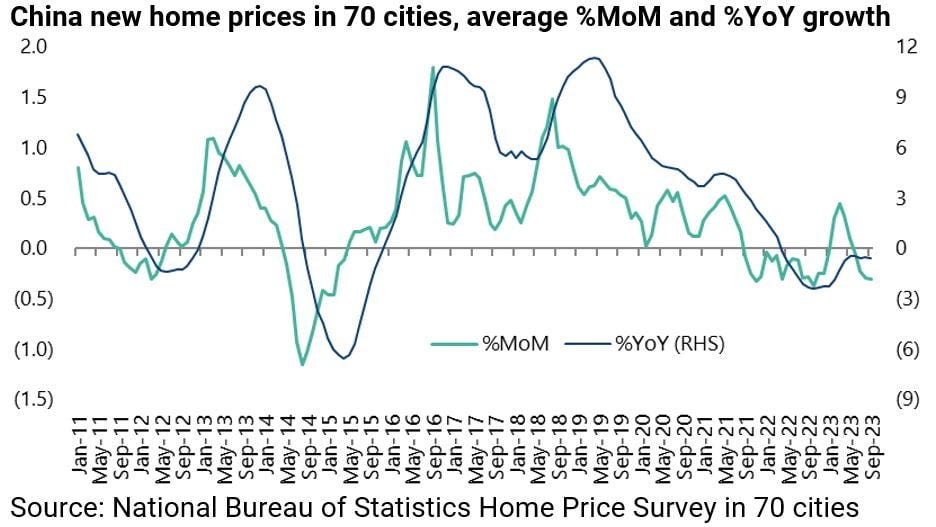

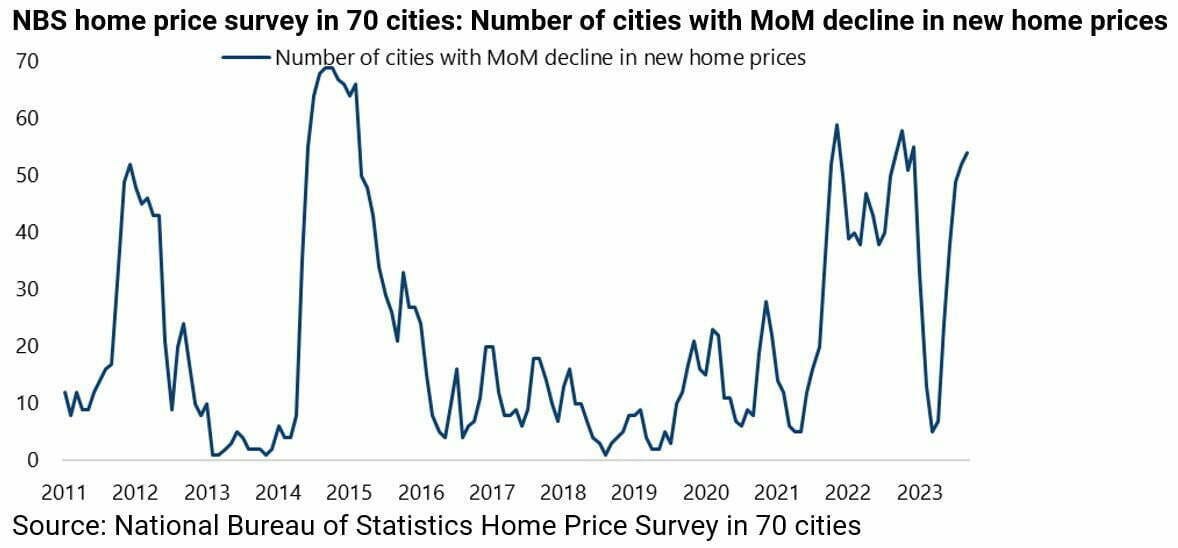

Meanwhile, the latest official property price data shows that home prices continue to decline.

New home prices in 70 cities surveyed by the National Bureau of Statistics declined by an average 0.3% MoM and 0.57% YoY in September, with prices declining MoM in 54 cities, up from 5 in March.

Why Isn't China's Central Bank Panicking?

The key point on China, amidst the continuing deteriorating news flow, is that the authorities’ focus remains on incremental easing in stark contrast to the ‘shock and awe’ monetary and fiscal easing investors have become accustomed to in Washington in the post-2008 era.

The best explanation of why there is not more evidence of alarm or panic in Beijing was provided in an article in the Qiushi Journal published on 15 August in response to the publication at that time of weak mainland data.

The article was based on the contents of a speech given by President Xi Jinping to top cadres on 7 February this year on the study and implementation of Xi’s thought in a new era of socialism with Chinese characteristics (see South China Morning Post article: “Xi Jinping speech calling for patience released amid China’s economic gloom”, 16 August 2023). Qiushi is an official organ of the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Committee.

In this speech Xi says that common prosperity is a “long-term mission” and that China cannot simply “follow the beaten path”.

Xi condemned Western modernisation saying it pursues the maximisation of the interests of capitalists instead of serving the interests of the vast majority of people, and was characterised by “wars, slavery, colonisation and plunder”.

Stressing the challenge posed by China’s large population and rural-urban development gap, Xi also highlighted in the same speech how some developing countries have been stuck in the “middle-income trap” as they have not solved the problems of polarisation and stratification.

The above message highlights a fundamental point too often lost in the topical discussion of late of whether China has entered a Japan-style balance sheet recession.

That is the ideological or “belief system” driving China’s current political leadership.

Clearly, there was no such political issue in Japan.

Meanwhile, the practical issue for investors is the extent to which this political context makes it more difficult for the technocrats to manage the fallout from the weakening residential property market, in terms of the ripple effects from financially stressed private property developers to local government finance vehicles to defaulting wealth management products and the like.

The other point is that the current Chinese government does not like bailouts, particularly of fat cats.

In this respect, Beijing’s stance remains more akin to Calvinist free market fundamentalism and advocacy of sound money than many might suppose.

Indeed the contrast with the failure of Silicon Valley Bank, where all the uninsured depositors were bailed out, could not be more extreme.

The average depositor in SVB had more than US$4m in the bank and 96% of the deposits were above the US$250,000 FDIC insurance limit.