Why The Bond Bear Market Marches On

Its Time to Fade the Rally

Author: Chris Wood

The announcement by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) in late June that it was raising its forecast for America’s fiscal deficit this year to US$1.915tn, by 27% from US$1.507tn in four short months since the previous estimate in February, is proof, if it was needed, that federal government finances are out of control.

This writer repeats the point that Treasury bonds are in a structural bear market.

Investors should take advantage of the recent rally on softening US data to exit positions.

Tactically, the rally can certainly continue if the data continues to soften, which is probably the base case.

Meanwhile, the trend line on the long-term log scale chart of the ten-year yield is now around 2.57%, as shown in the chart below.

Still, with neither US presidential candidate showing the remotest interest in fiscal retrenchment, this is a rally in a bear market.

The Treasury has of late become dangerously addicted to short-term issuance.

US Treasury bills, with maturities up to one year, accounted for an annualised 85.1% of gross marketable Treasury issuance in the 12 months to July.

Meanwhile, as Jerome Powell must doubtless be fearing, it is likely only a matter of time before the Federal Reserve comes under renewed pressure to buy more Treasury bonds; though for now it is still selling them based on the reduced scale of quanto tightening announced on 1 May.

The Fed still owns a lot of Treasury bonds after years of balance sheet expansion, US$4.41tn to be precise, though down from a peak of US$5.77tn in June 2022.

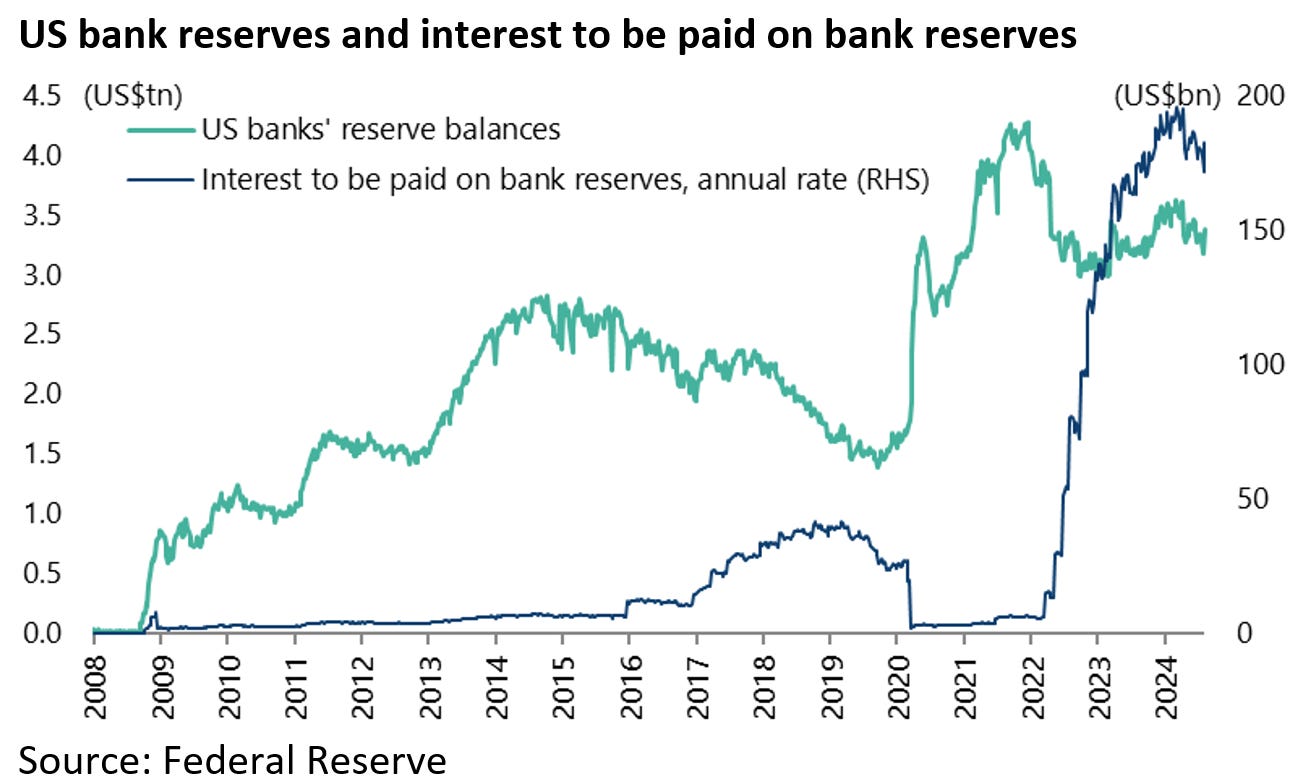

One consequence of the quantitative easing era since late 2008 is that US commercial banks accumulated large reserves which they have been paid interest on by the Fed.

Thus, the Fed began in October 2008 paying commercial banks interest on the reserves they hold at the central bank.

With the rise in short-term interest rates in recent years, the amount being paid to the banks for essentially doing nothing has exploded, while the reason the Fed and other G7 central banks are paying interest is presumably to prevent an inflationary surge in credit expansion.

As a consequence, the Fed is now paying an estimated annualised US$182bn to commercial banks, up from only US$6bn in early March 2022.

US Bank Reserves Could Easily Become Political Ammo

Still, it has long been evident to the writer that the trend of central banks paying huge amounts in interest to commercial banks is ripe for politicians of a more populist strain to exploit.

Indeed, it is a surprise that there has not been more focus on this in recent years.

Still, Britain’s Nigel Farage raised precisely this issue in late June.

His Reform UK Party, which got 14.3% of the vote in the recent British general election, has advocated ending the payment to the banks altogether, which, it says, could save £35bn a year (see Bloomberg article: “BOE Reserves Enter UK Election Debate as Politicians Chase Cash”, 13 June 2024).

But that is peanuts compared with what the Fed is currently paying US commercial banks, namely around US$182bn.

Now it may be argued that quantitative easing, and the related issue of central bank payments to commercial banks, is too esoteric a subject to interest the electorate.

But if an ordinary voter is told that banks are being paid this amount simply for depositing funds with the central bank, that is an issue ripe for exploitation by a talented “populist”, be it Farage or Donald Trump.

If the voter is also told that the payments are an indirect consequence of the 2008 financial crisis which triggered the onset of quanto easing, then the topic will get even further traction.

That is because the origin of the continuing “populist” phenomenon in Western politics was, in this writer’s longstanding view, the bailouts triggered by that crisis.

This sent the message that there was one rule for Wall Street and another for Main Street.

Indeed, it is fair to say that the Trump phenomenon—and it is a phenomenon regardless of whether he wins or loses the coming election—would not exist were it not for those bailouts.

Treasury Rally Has Been Good News for A Japanese Government Actively Selling

Meanwhile, returning to the Treasury bond market, Japan’s Norinchukin remains an interesting example of an institution which has sustained massive losses owning Treasuries.

The bank announced last quarter that it plans to sell about US$63bn (Y10tn) of its holdings of G7 government bonds, mainly Treasuries, by the end of March 2025 or about 43% of its foreign bond portfolio of Y23tn, after disclosing unrealized losses of Y2.19tn in its bond portfolio at the end of March.

In this respect, the recent rally in Treasuries has come at a good time for the bank, which holds deposits from Japanese farm and fisheries cooperatives.

If Norinchukin is now selling, the Japanese still own a lot of Treasury bonds, though down from the peak.

To be precise, they owned US$1.13tn of Treasury securities at the end of May, down from a peak of US$1.33tn in November 2021.

In this writer’s view, it has made sense to own equities over government bonds in the G7 world ever since the monetary inflation unleashed by the Fed in the spring of 2020.

Meanwhile, the rising geopolitical risks, and the escalating spending on defence, is also inflationary.

Indeed, the increased aid to Ukraine is one major reason for the CBO’s latest increase in its estimate of this year’s US fiscal deficit.