What a "No Landing" Means for Your Portfolio

Are bonds or stocks the better bet?

Author: Chris Wood

It is important in observing markets to monitor alternative narratives and, like any good trader, not to be stuck rigidly to any specific view.

If this writer has been focused over the past year and more on the considerable lags in the impact of monetary tightening in this cycle, the current reality is that financial markets continue to question the soft-landing consensus prevailing at the start of this year on the growing view that there will be no landing at all.

Such an outcome would be equity bullish but Treasury bond bearish, as it implies higher nominal GDP growth.

And so far in 2024, equities have been outperforming Treasury bonds significantly, as indeed they have also done dramatically since the Covid-triggered bottom in March 2020.

The S&P500 has risen by 11.3% year-to-date on a total-return basis and is up 152% since bottoming on 23 March 2020.

By contrast, the Bloomberg US Long (10Y+) Treasury Index has declined by 6.6% year-to-date and is down 37% since 23 March 2020.

As a result, the S&P500 has outperformed the Bloomberg 10Y+ Treasury Index by 19.1% so far in 2024 and by an enormous 297% since 23 March 2020.

This writer has also been focused in recent months on the likely Fed policy reaction if the US labour market weakens.

The best lead indicator of a softening in the labour market remains the decline in hiring intentions in the monthly National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) small-business survey.

The NFIB small-business hiring plans index declined from 12% in February to 11% in March, the lowest level since May 2020, and was 12% in April.

Still, while this has been a good lead indicator of labour market weakening in previous cycles, the reality is that it is just a survey and for now there is no concrete evidence of real labour market weakness.

It is also the case that, while the latest NFIB survey shows SMEs paying an average interest rate of 9.3%, there is no concrete data on how much SMEs are borrowing at the aggregate level.

Similarly, with nominal GDP growth at 5.4% YoY last quarter, SMEs’ revenue growth should remain reasonably healthy.

Remember, nominal GDP growth averaged a robust 6.3% YoY last year.

The same evidence of health is reflected in the trend in corporate tax payments.

Federal government US corporate income taxes received rose by 14% YoY in April and were up 13% YoY in the six months to April.

What is Bank Lending Telling us About the Economy?

Meanwhile if the labour market is, at the end of the day, a lagging indicator, it is the case that credit growth is a leading indicator.

The latest April Federal Reserve Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey (SLOOS) released in early May showed a further decline in the net percentage of banks tightening lending standards.

Thus, a net 11.6% of US banks tightened lending standards for all loans over the past three months, down from 20.6% in the February survey and 42% in April 2023.

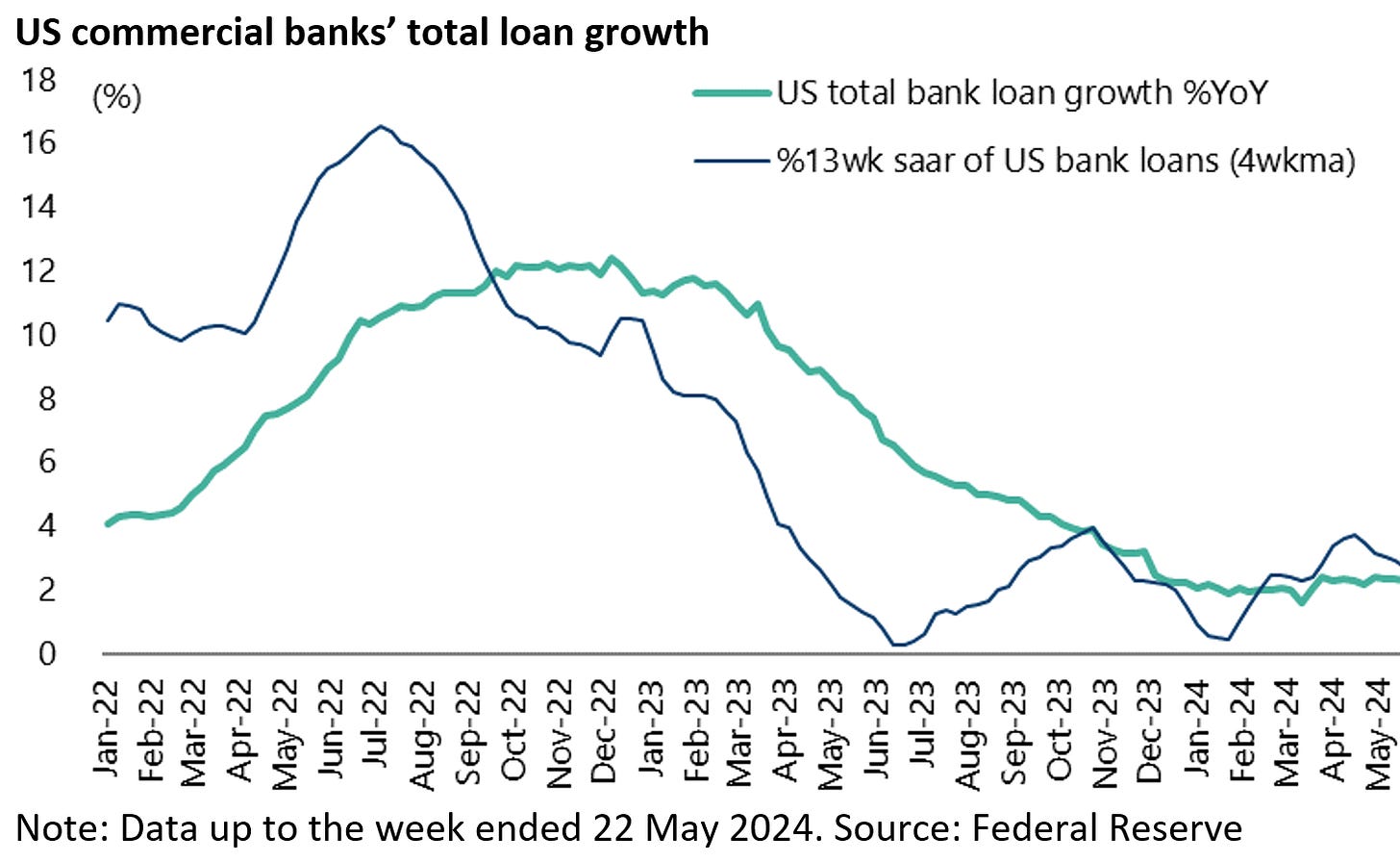

This is worth mentioning because there are some initial signs that commercial bank lending has begun to turn up in America after having been in a declining trend since December 2022.

US commercial banks’ total loan growth slowed from US$1.32tn or 12.4% YoY in early December 2022 to US$190bn or 1.6% YoY in mid-March 2024 and was up US$275bn or 2.3% YoY in the week ended 22 May.

On a three-month annualised basis, US bank loans rose by an annualised 2.7% in the 13 weeks to 22 May, up from 0.4% in late January.

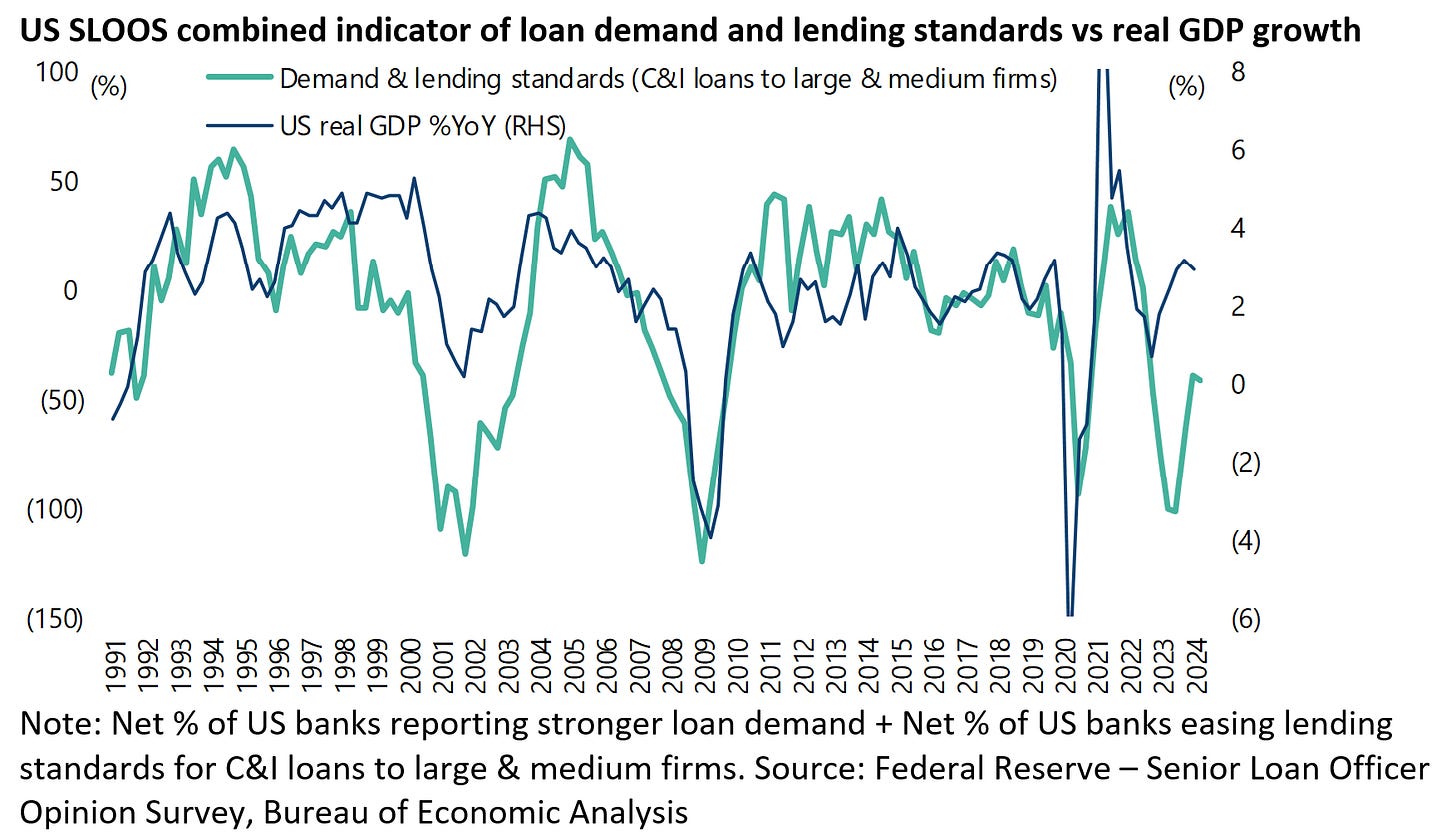

On this point, it has been a notable feature of this cycle that the correlation between the combined indicator of lending standards and loan demand in the so-called SLOOS (Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey) and the state of the US economy has so far broken down, as reflected again in the following chart.

The best guesses as to the explanation for this remain the continuing flows into private credit, and the related area of shadow finance, as well as the fact that America continues to run large fiscal deficits.

The fiscal deficit was still running at an annualised 5.9% of GDP in April.

If bank credit growth is now in an accelerating trend, that would really support the “no landing” thesis. It would also be positive for cyclical equities, as it would be negative for those hoping for a resumption of monetary easing and a return of inflation to the formal 2% target.

Who Suffers From No Rate Cuts?

This also raises the issue of who will be the most impacted by the lack of a renewed Fed easing cycle.

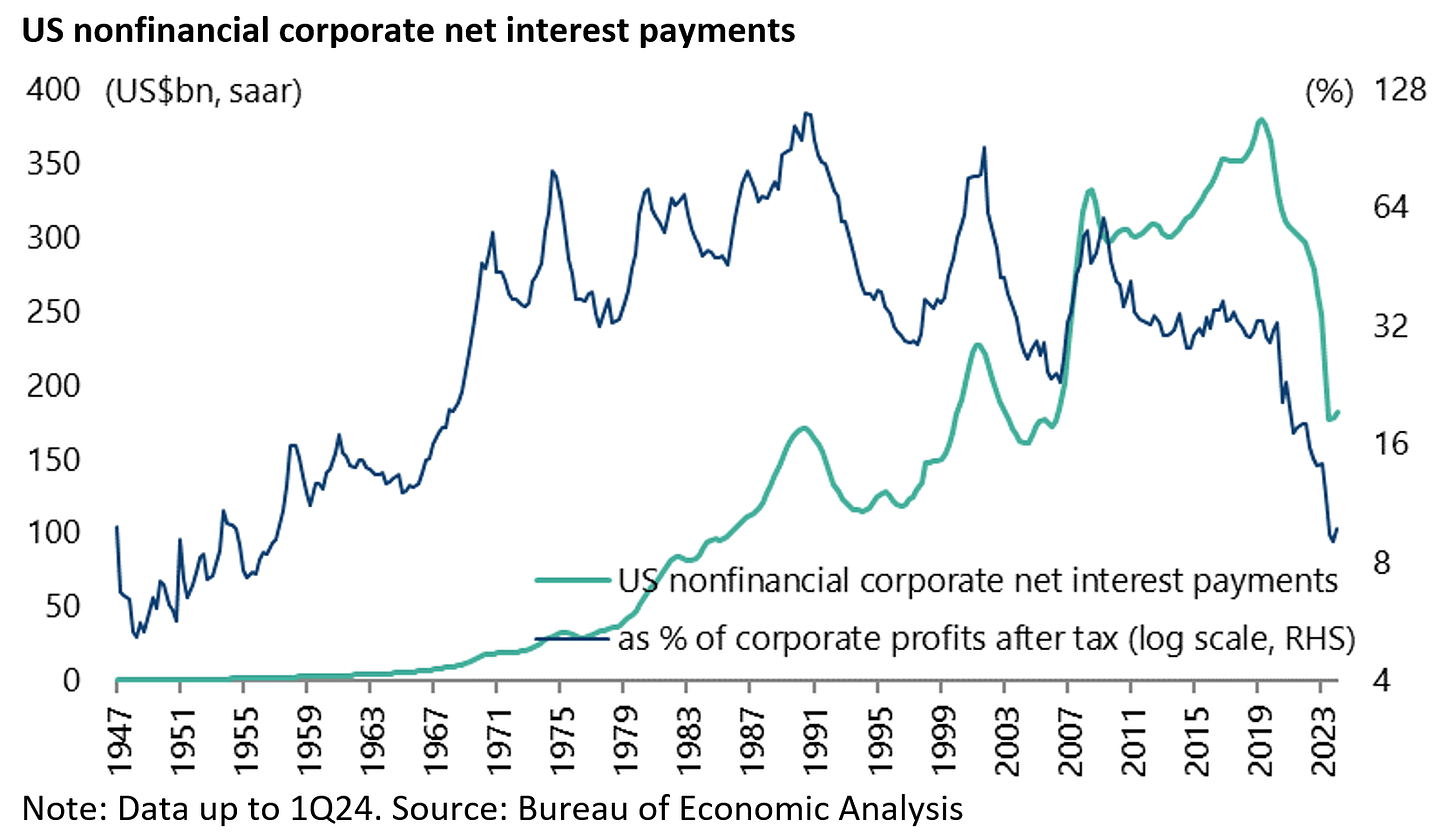

On this point, it is clear that it is not US-listed companies.

The remarkable point is that net interest payments of the US corporate sector have declined in this monetary tightening cycle, a trend driven by the large cash balances of the Big Tech companies combined with listed corporates’ refinancing of their long-term debt when bond yields were at all-time lows.

Thus, US nonfinancial corporates’ net interest payments as a percentage of profits after tax have declined from 18.1% in 1Q22 to 9.1% in 4Q23, the lowest level since 4Q56, and were 9.8% in 1Q24, based on the latest national accounts data.

In absolute terms, net interest payments declined by 31% from an annualised US$262bn in 4Q22 to US$181bn in 1Q24 and are down 52% from the peak of US$380bn reached in 2Q19.

In this respect, the real vulnerability in the US to a lack of Fed easing, let alone renewed tightening, would be the private equity industry.

On this subject, it is worth repeating the point highlighted in a recent highly recommended Bain report on that industry (see Bain & Co. report: “Global Private Equity Report 2024”, 11 March 2024).

This estimated that private equity companies were sitting at the start of this year on an astonishing 28,000 unsold companies globally worth a hoped for more than US$3tn.

This must constitute one of the largest cases of financial constipation ever in the history of corporate finance.

The simple point is that the longer it takes for monetary easing to commence, the bigger the potential problem for this industry, which was, after all, the biggest beneficiary of the zero-rate era.

Meanwhile, the higher rates available to lenders are the reason for the continuing boom in private credit.

But those high returns are self-evidently somewhat risky, as money is for the most part being lent at rates well above prevailing nominal GDP growth.

It is also the case that a significant part of the private credit industry is funding private equity.