Understanding China's "Anti-Involution" Campaign

Author: Chris Wood

China remains the best example of a country which has not succumbed to the pressure tactics so effectively deployed against many other countries by the current administration in Washington.

There is also the continuing reality that China still has leverage on the rare earth issue, which it has clearly chosen to apply again if the circumstances warrant.

But Donald Trump has seemed happy of late to de-escalate in the hope of securing a long-sought face-to-face meeting with Chinese leader Xi Jinping in the autumn.

Still, it would be unwise in the extreme to write off completely the influence of Washington’s national security lobby, most particularly as Trump’s U-turn on Ukraine relative to what he campaigned on in the presidential election campaign, makes it clear that it still has real influence.

That said, a face-to-face meeting between the two leaders raises the potential for a real breakthrough given the transactional nature of the current US president.

Indeed, the Chinese president has found himself in the strong negotiating position of being lobbied for a meeting.

It now seems that the American president has got his way. After a call with Xi on 19 September, Trump said that he would meet the Chinese president at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit in Gyeongju, South Korea in late October.

Anti-Involution is China’s Attempt at Stimulus

Then there is the issue of the state of China’s domestic economy.

If investors have waited in vain in the past few years for more aggressive stimulus out of China, there has been renewed evidence in recent months on the Chinese authorities’ concern about deflation.

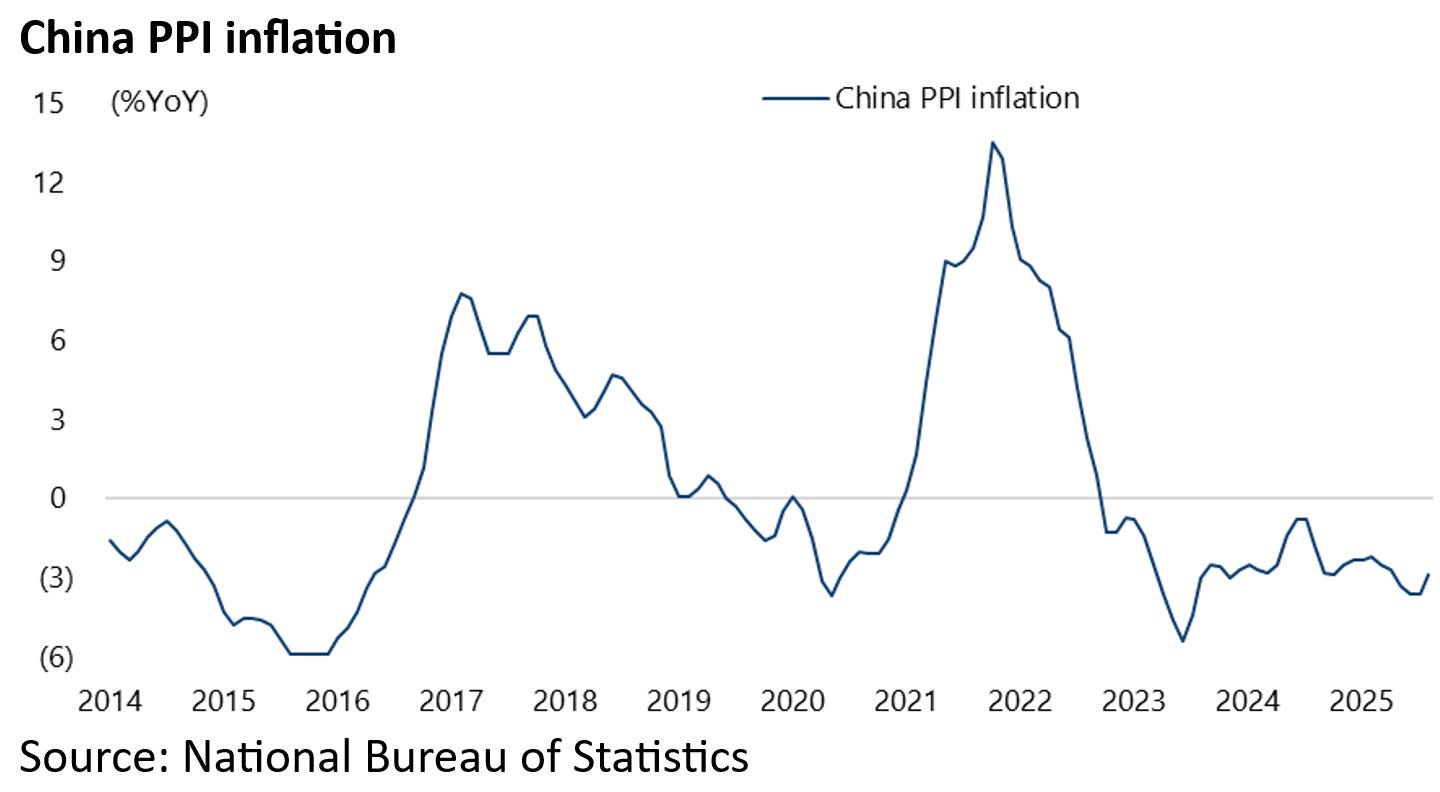

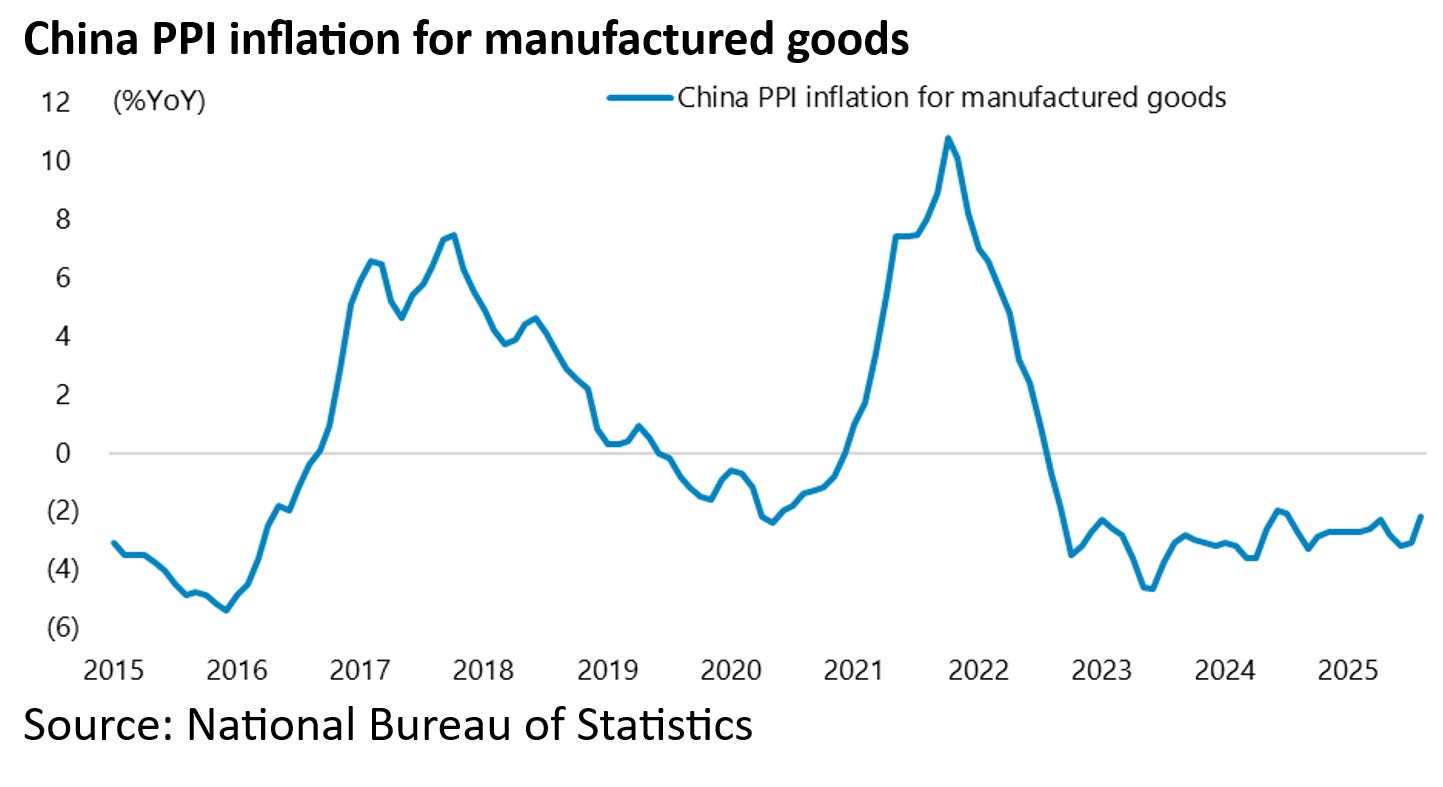

PPI has now been negative on a YoY basis for 35 consecutive months since October 2022, running at -2.9% YoY in August.

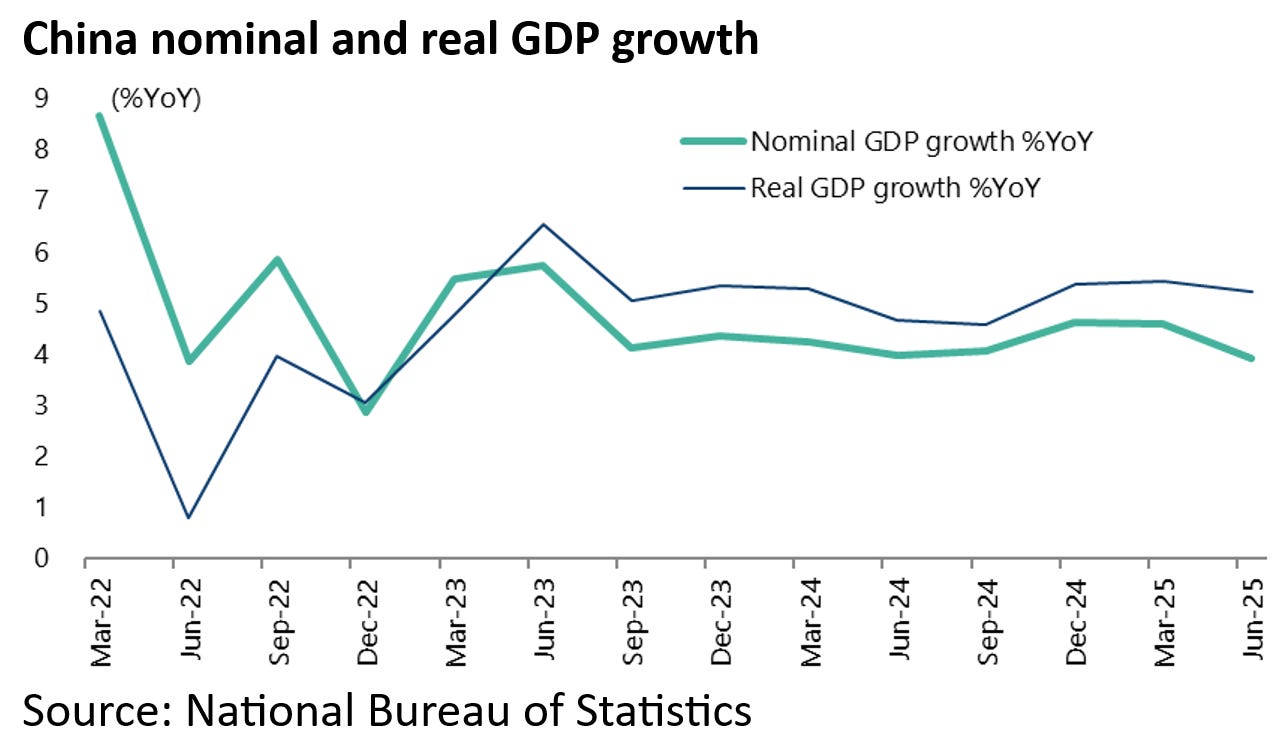

While YoY nominal GDP growth has been lower than YoY real GDP growth for the past nine quarters.

That concern has been reflected in what has become known as the “anti-involution” campaign.

The campaign appears to have had its formal origin in President Xi Jinping’s call at a meeting of the Central Commission for Financial and Economic Affairs (CCFEA) on 1 July for the need to “promote the orderly exit of obsolete production capacity” (see South China Morning Post article: “China’s top leadership takes aim at ‘disorderly low-price competition’”, 2 July 2025).

While the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) jointly issued on 24 July a draft amendment to China’s Pricing Law for the first time since 1998 to curb what the authorities describe as “disorderly low-price competition”.

The amendment prohibits businesses from selling below cost to eliminate competitors or to monopolize the market, except in the case of legitimate discounts such as seasonal promotions or clearing excess inventory.

It should also be noted that this amendment was not in the original 2025 legislative plan.

So releasing such a draft is another sign of the increased urgency to deal with deflation and so-called involution (内卷).

These latest measures follow growing official focus on the negative aspects of excessive competition or what has been described in the Global Times, an English-language newspaper under the People’s Daily, as “rat race-style” competition (see Global Times article: “China releases draft law amendment to stop ‘rat race-style’ market competition”, 24 July 2025).

As discussed here recently, the authorities in May and early June called in both EV makers such as BYD and food delivery internet platforms such as JD.com and Meituan to warn against excessive price cutting (see Key Takeaways From Our Recent Trip to Beijing, 6 August 2025).

So, the latest campaign is not just about excess capacity, though excess capacity is a part of it.

Similar to China’s Supply Side Reforms of 2015?

The obvious historical comparison is with China’s supply-side reforms of 2015-2018.

Ten years ago, the focus was primarily on steel, coal and cement, with the stated policy goal “phasing out inefficient, polluting capacity”.

But this time, the policy targets not only traditional sectors such as iron and steel, building materials, chemicals and coal, but also high growth areas such as solar, lithium batteries, electric vehicles and internet e-commerce.

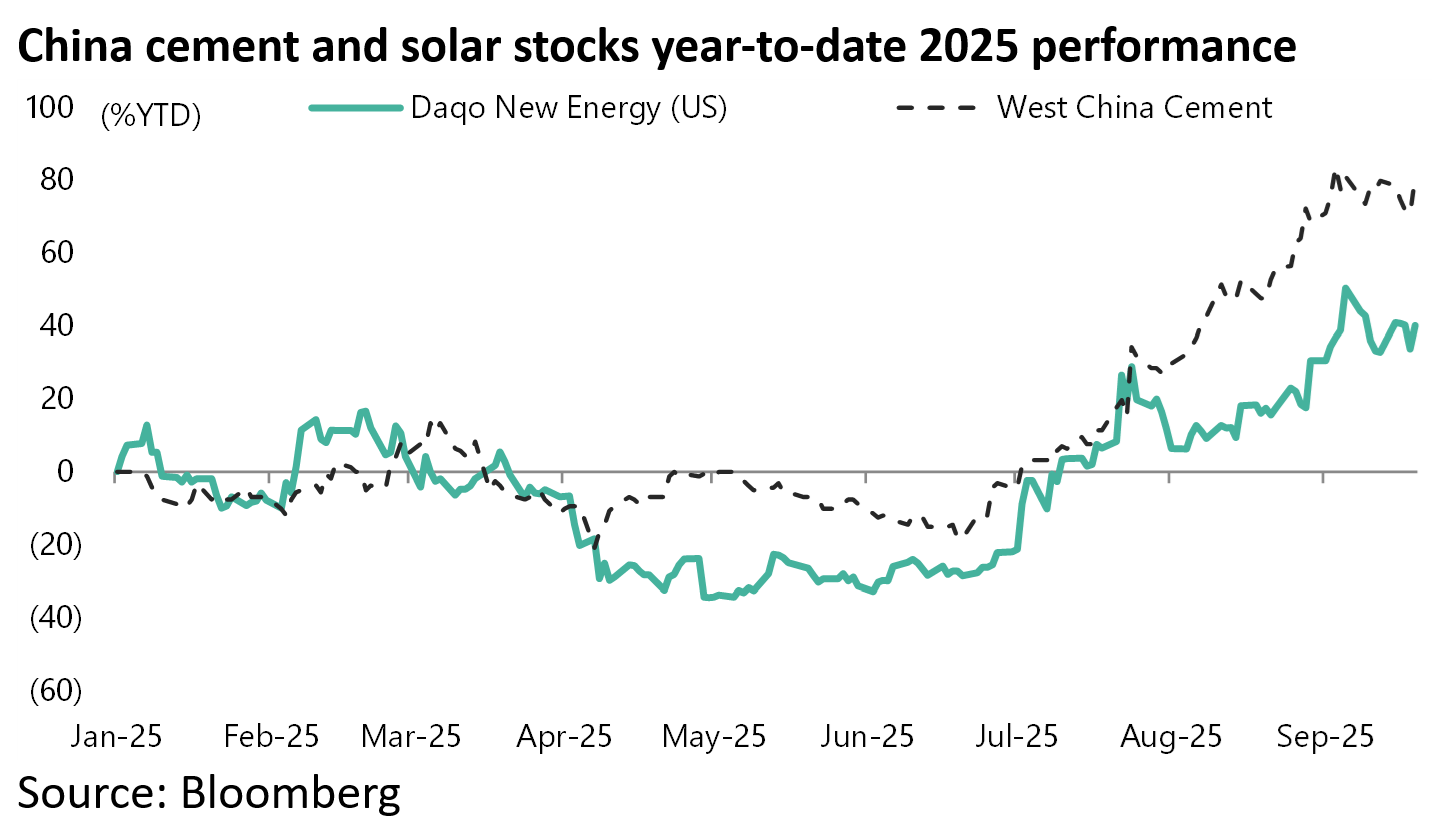

The growing investor focus on the latest policy has triggered rallies in the likes of cement and solar stocks in China.

Weak Labor and Housing Markets Make Enforcement Difficult

Still, domestic demand is much more subdued than was the case ten years ago when in certain respects the deflationary shock caused by supply-side reform, in terms of cuts in capacity, was offset at that time to a significant extent by the boost to demand triggered by the monetisation of the shantytown redevelopment scheme which created demand for residential properties, particularly in the smaller cities of China.

The result then was a dramatic rebound in PPI and a return to double-digit nominal GDP growth.

Thus, PPI inflation rose from a negative 5.9% YoY in December 2015 to a positive 7.8% YoY in February 2017.

While nominal GDP growth surged from 6.6% YoY in 4Q15 to 11.8% YoY in 1Q17. It was only 3.9% YoY in 2Q25.

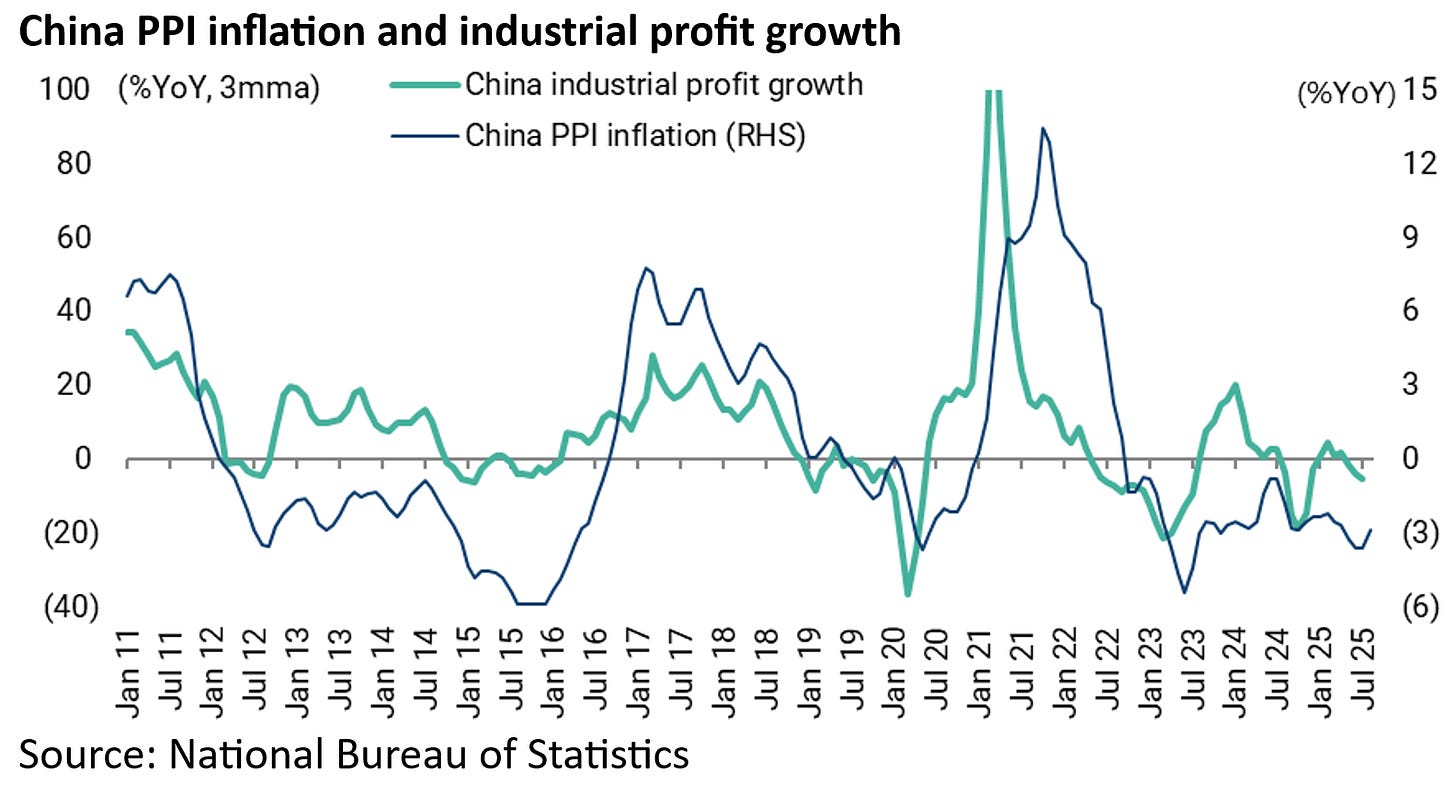

This was very positive for a Chinese stock market where domestic investors have always been focused on the close correlation between PPI and industrial profits at a time when the residential property market, not exports, was the key driver of the economy.

The correlation between PPI inflation and industrial profit growth was 0.75 between 2011 and 2019 prior to the pandemic.

The situation is very different now given the continuing residential property downturn, where the latest data suggests renewed weakness, and given the reality of both deflation and depressed consumer sentiment.

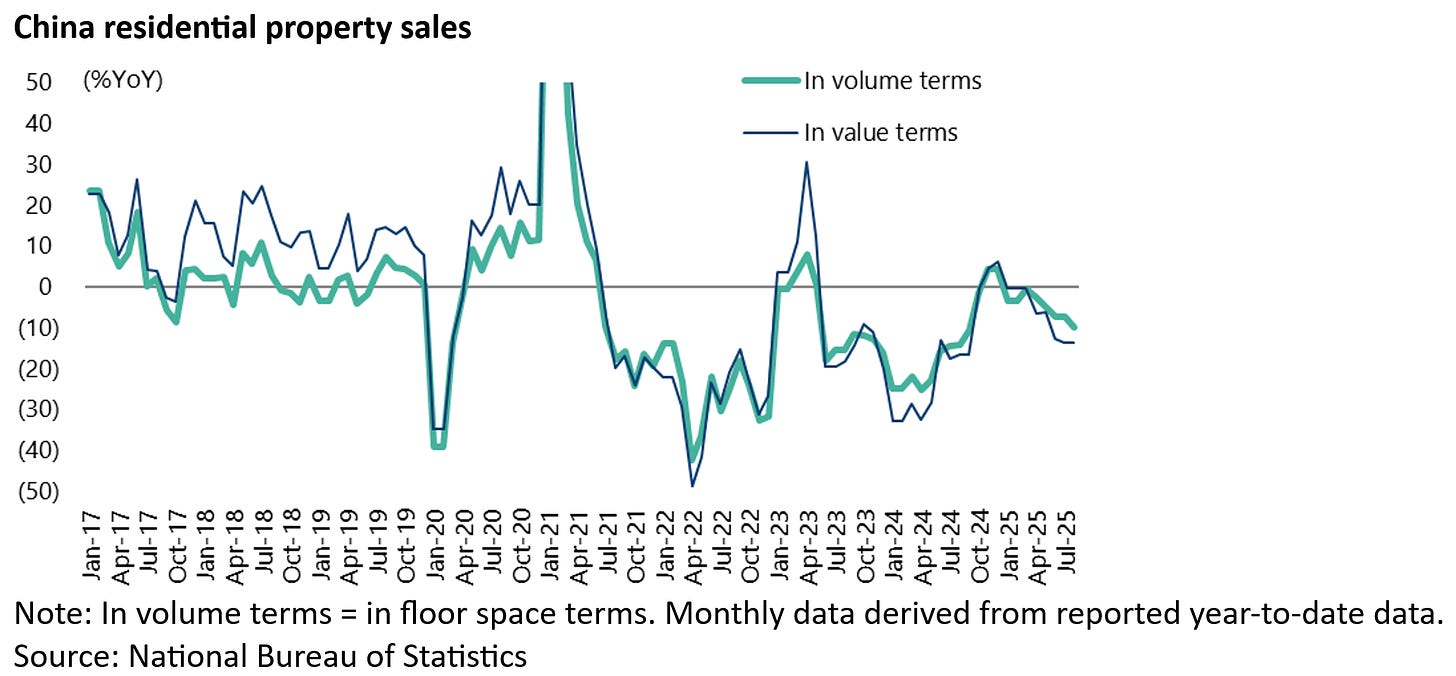

The official National Bureau of Statistics data shows that nationwide residential property floor space sold declined by 9.7% YoY in August and were down 13.6% YoY in value terms.

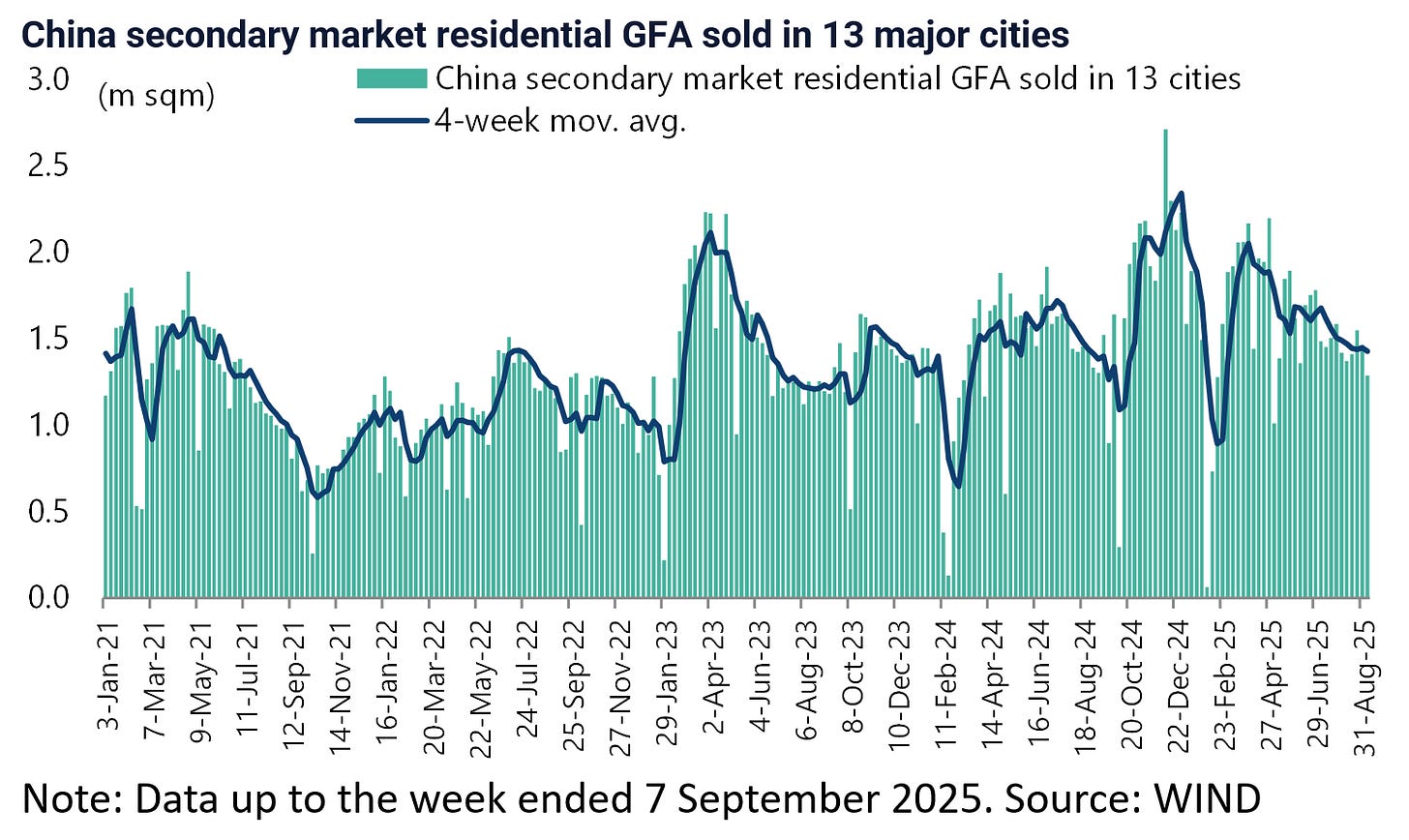

While weekly secondary market residential floor space sold in 13 major cities declined by 2.1% YoY in the first 10 weeks of 2H25 ended 7 September, after rising by 19.4% YoY in the first half of this year.

Enforcement of Anti-Involution Reforms has Been Weak so Far

Meanwhile, the current round of so-called “anti-involution efforts” are based primarily on industries exercising self-discipline, with relatively weak enforcement.

By contrast, in the previous supply-side reform, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) took the lead with specific targets for capacity reduction assigned to local governments and with specific timetables to meet those targets.

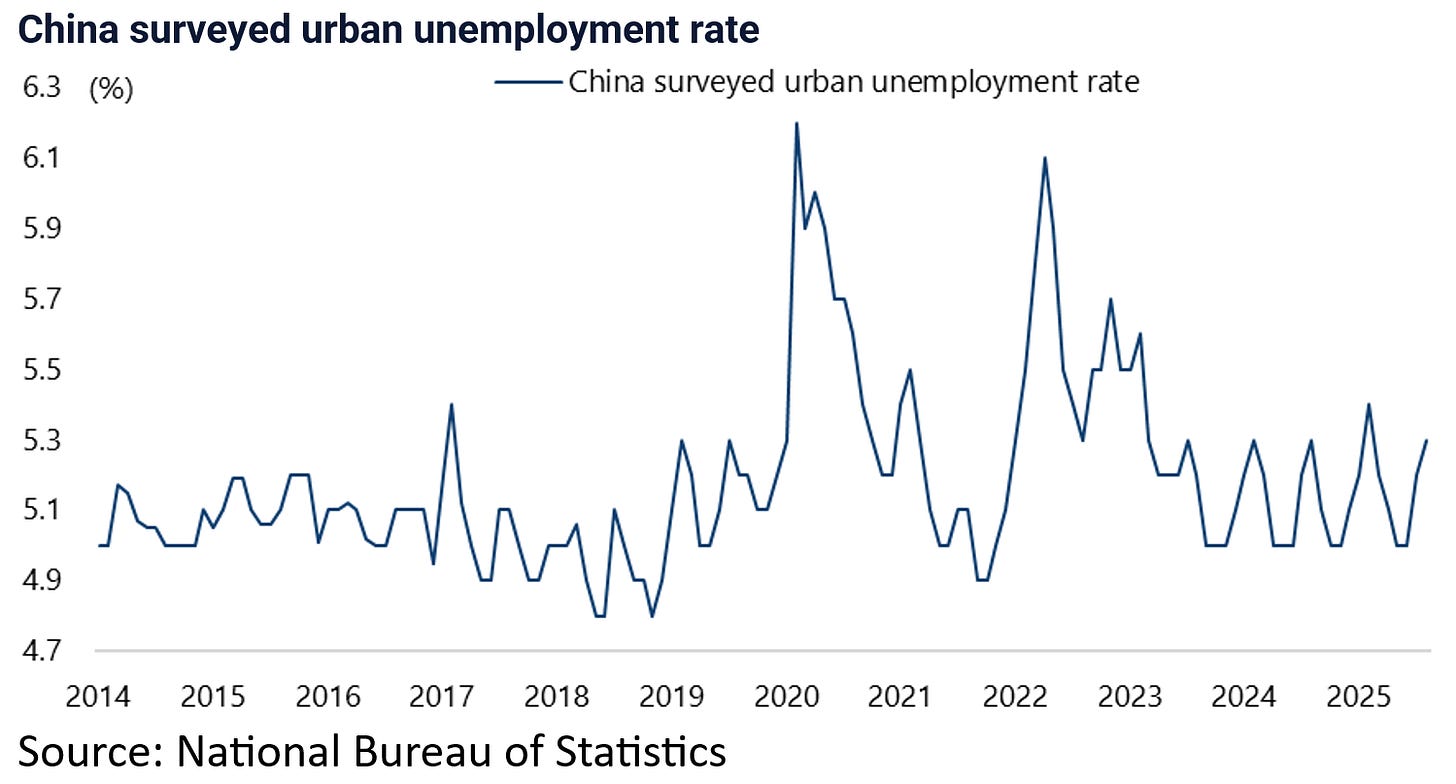

Clearly, the risk of a similarly aggressive approach in the current macro context of weak domestic demand would be a destabilising rise in unemployment in an economy where employment trends are clearly not that healthy.

This is also why the current policy focuses more on production cuts than reducing excess capacity. As regards the state of the labour market, the surveyed urban unemployment rate is now 5.3%.

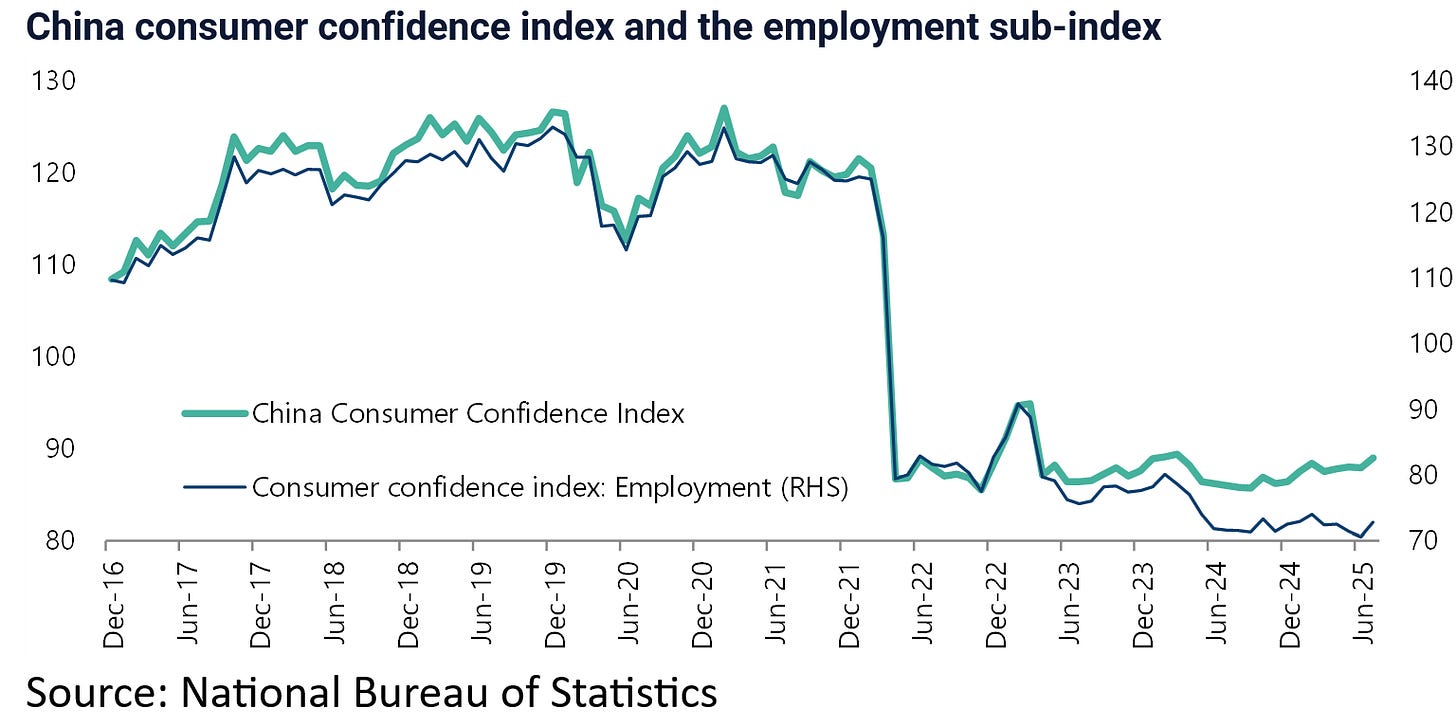

While the employment sub-index of the consumer confidence index declined from 74.0 in February to a record low of 70.6 in June and was 72.8 in July.

Manufacturing Capacity Continues to Increase According to the Data

If “anti-involution” is not quite supply-side reform, it would be wrong to dismiss outright the significance of this latest policy initiative.

It is a positive that the authorities are focused on excessive price competition in both the legacy and growth sectors, as well as on the need to curb capacity expansion.

On that point, the statement released following the Politburo meeting in late July emphasized the need to address “disorderly competition among enterprises” and to monitor local governments competing to attract investments in the same sector.

The end goal is to end deflation and increase corporate profits to a healthier level, which is where the longstanding correlation between industrial profits and PPI is relevant.

But for now there is no clear evidence of improvement.

On a related point, it is interesting to note that PPI for manufactured goods has now been declining on a YoY basis for 37 months, falling by 2.2% YoY in August.

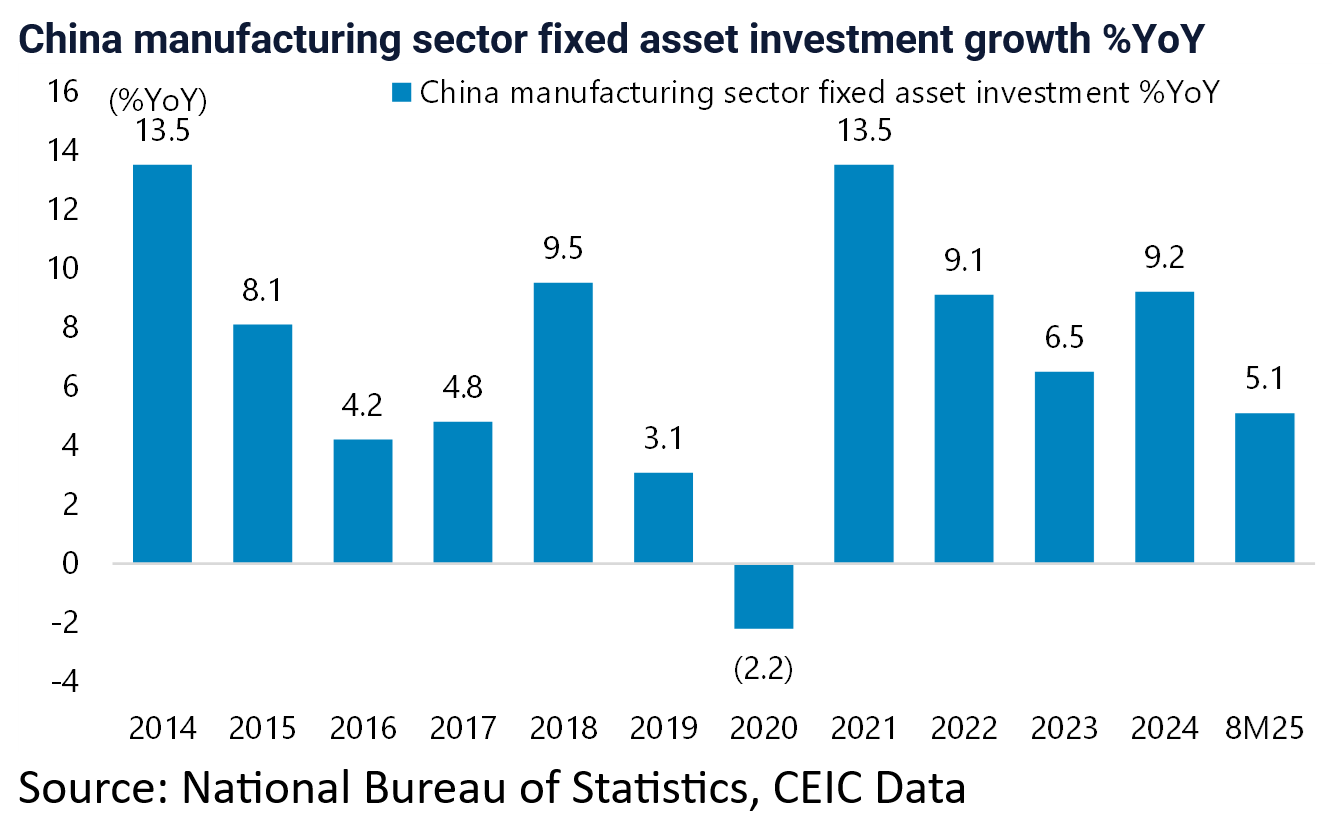

While the official data shows that fixed asset investment (FAI) for the manufacturing sector still increased by 5.1% YoY in the first eight months of 2025.

This suggests manufacturers are still increasing capacity.

Bank Lending to the Manufacturing Sector is Slowing, Potentially Signaling Capacity Growth Will Slow as Well

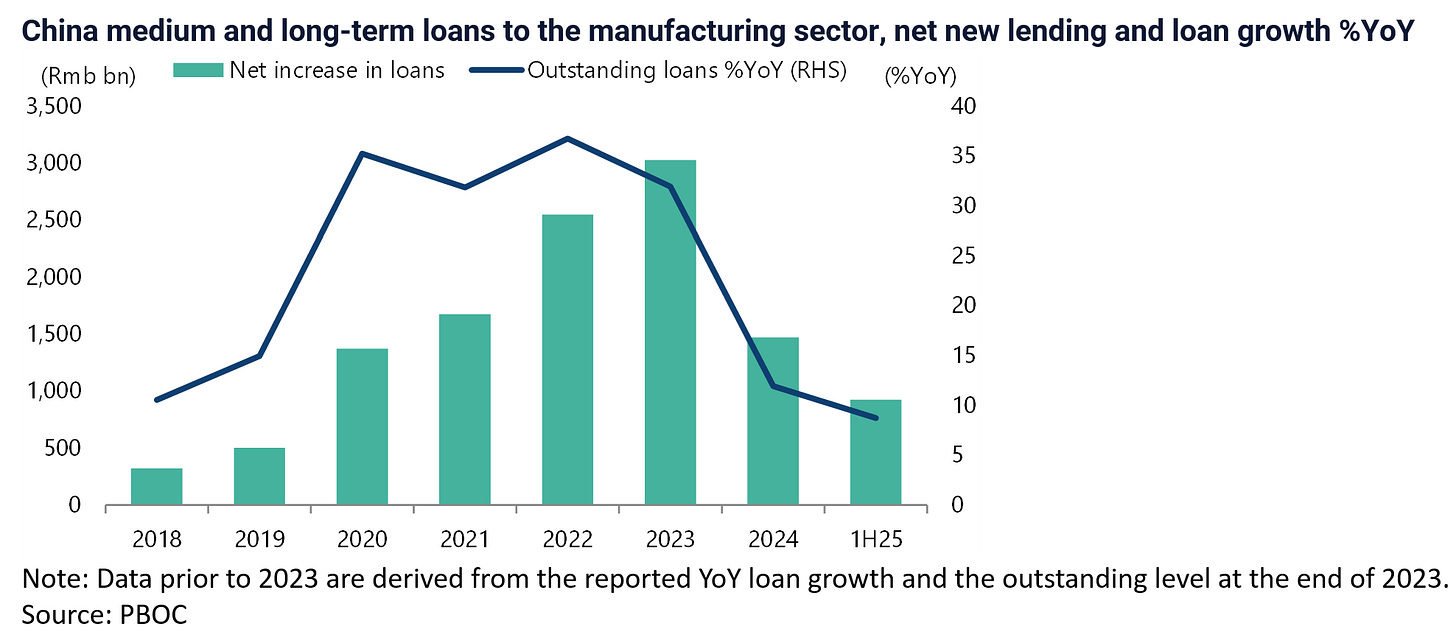

Still, a sign that manufacturing capex may be slowing more than the official FAI data suggest is reflected in bank lending data for the manufacturing sector.

Thus, outstanding medium and long-term loans to the manufacturing sector rose by 8.7% YoY at the end of 1H25, down from 11.9% YoY in 2024 and over 30% YoY in each of the previous four years since 2020 when banks were responding to the Xi campaign to build “new productive forces”.

Similarly, net new bank lending to manufacturing was Rmb921bn in 1H25 and Rmb1.5tn in 2024, down sharply from an estimated Rmb3tn in 2023.