The World is Splitting into Two Parallel Economies Before our Eyes

Author: Chris Wood

There have been some interesting geopolitical trends of late.

For example, the chief outcome of the somewhat ballyhooed meeting of the BRICS countries in Johannesburg in late August was the announcement that Saudi Arabia and the UAE, among other countries, have been invited to join the grouping.

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa announced on 24 August after the summit that the BRICS members have decided to invite Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates to become full members of BRICS, effective from 1 January 2024.

Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Faisal bin Farhan has said that the kingdom will study the details and take “the appropriate decision” and that BRICS was “a beneficial and important channel” to strengthen economic cooperation.

While UAE President Mohamed Bin Zayed also praised the group’s decision to include his country in BRICS.

Such an outcome would mean that the BRICS grouping would control 40% of world oil exports at a time when the overwhelming probability is that US shale oil production has peaked.

This is, potentially, a momentous development.

The current BRICS members accounted for 14.2% of world total crude oil exports in 2022, while the newly invited BRICS members accounted for a further 25.4% of the total.

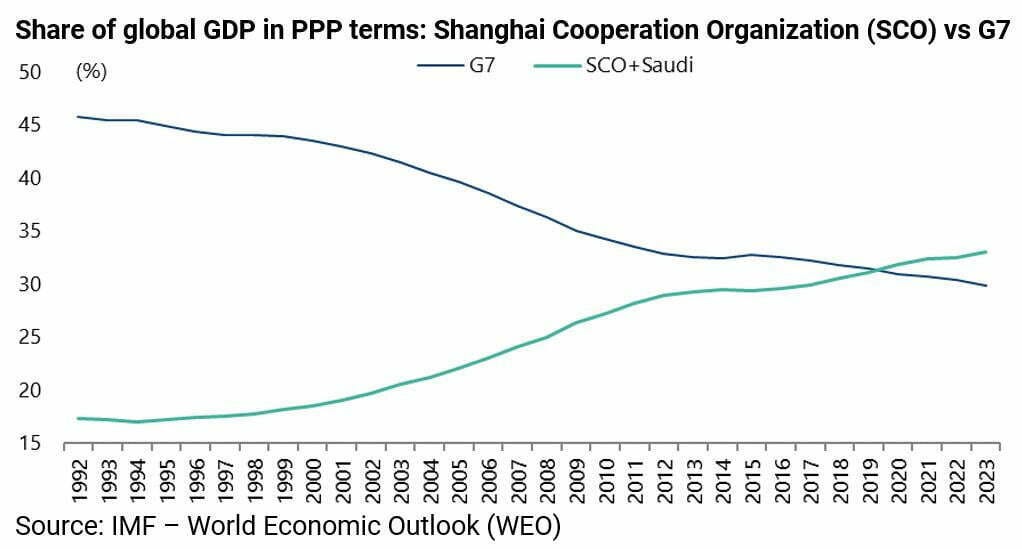

Staying on the geopolitical theme, it is also worth highlighting Saudi Arabia’s decision in late March to join the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) as a so-called dialogue partner, the first step before acquiring full membership.

That body currently comprises the following nine member countries: China, India, Iran, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

If Saudi is included, this organization would represent 33% of the global economy compared with the G7’s 30%, and 43% of the world’s population.

The World is Splitting Into Two Great Economic Powers Once Again

Saudi’s proposed membership of the SCO, combined with its seeming agreement to sell oil in other currencies than the US dollar when Saudi rolled out the red carpet in Riyadh for visiting Chinese President Xi Jinping last December and the Beijing-brokered restoration of Saudi’s relationship with Iran in March, are all recent manifestations of the emerging reality of a multipolar world, a trend which does not get the attention it merits in the Western media but which will form the content of many future history books.

Then there is the issue of the continuing conflict in Ukraine where many in the G7 world have continued to ask why Beijing is not doing more to distance itself from Moscow’s stance in the conflict.

The obvious answer is that Beijing and Moscow are essentially on the same side in the effort to build a parallel economic system that provides some hedge against the ever-greater weaponisation of the US dollar in recent years, a trend which, as previously noted here, reached its seeming ultimate manifestation in the decision in late February 2022 to freeze Russia’s foreign exchange reserves (see A pronounced slowdown in inflation is coming, 14 September 2023).

This effort includes not only increasing trade flows outside the US dollar but also building infrastructure to connect Eurasia and so reduce reliance on US navy-controlled sea routes.

Then there is the development of financial infrastructure to reduce dependence on the likes of Swift.

So, while Beijing was undoubtedly severely embarrassed by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, given its long held stance of not interfering in other countries’ sovereignty, it has not been the cause of a total rupture in the relationship, most particularly as the Chinese stance remains that the West escalated the situation by encouraging Ukraine to believe it can join NATO, a development which has always been a red line for Moscow.

Ukrain Could Return to the Negotiating Table

Meanwhile, the upshot of the NATO summit in Vilnius in July was that Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskyy appeared to have overplayed his hand by his demands for more financial and military support and for a fast-tracking of NATO membership.

Fortunately, for those wishing to avoid nuclear conflict, Washington and Berlin have come out against near-term NATO membership for Ukraine.

The case for such a stance was well argued in an article in Foreign Affairs (“Don’t Let Ukraine Join NATO” by Justin Logan and Joshua Shifrinson, 7 July 2023), an organ which is the epitome of the Washington foreign policy establishment.

The result is that, if the Ukraine’s recent counter offensive does not result in significant territorial gains, as so far seems to be the case, then Kyiv’s stance could switch to seeking some kind of peace deal and perhaps commitment to future NATO membership in exchange for giving up some territory in the east of the country.

The incentive for the Ukrainians to start negotiating is clearly the risk of a popular reaction against funding the war in America and Europe, most particularly in America where both Donald Trump and Ron DeSantis, as the leading Republican presidential candidates, would look to end financing the conflict as quickly as possible based on the public comments they have made.

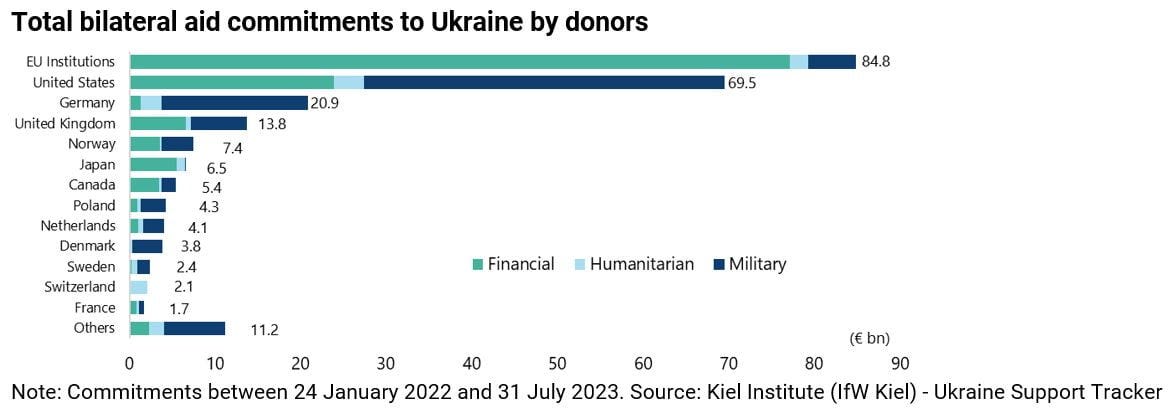

So far, America and Europe have spent or committed to spend €69bn and €155bn, respectively, on the conflict, which is a lot of money.

Meanwhile, it is worth remembering that, despite all the talk of sanctions, America is still importing enriched uranium from Russia just as Europe is importing Russian oil after it has been refined into diesel in India.

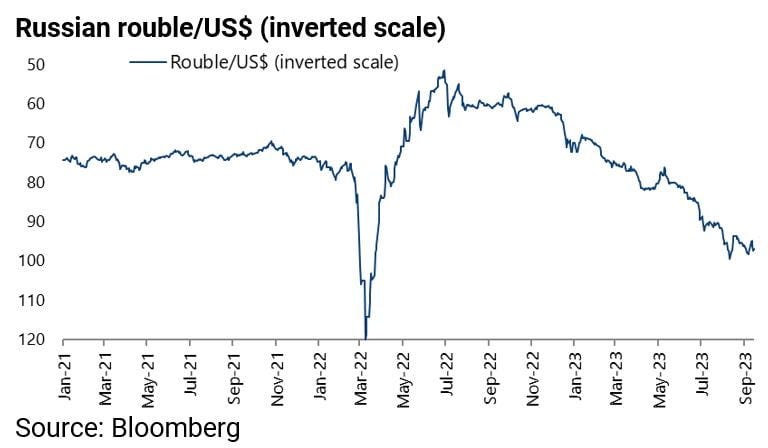

As for the state of Russia itself, the rouble has declined by 47% against the US dollar since peaking in late June 2022, depreciating from RUB51.45/US$ to RUB96.8/US$.

Still, this currency weakness may well be self-induced since a weaker exchange rate makes it easier for the Russian government to meet its fiscal targets, in terms of the dollar revenues from the sale of oil, gas, and other commodities being converted into greater amount of roubles.

Certainly, the state of Russia does not appear to be quite as disastrous as the neocons in Washington would like to make out, as amplified by their cheer leaders in the Western media.

As for the position of Putin, this writer has no inside track.

But it is far from clear to this writer if Putin’s position has been weakened or strengthened by the recent astonishing developments concerning the Wagner Group.

What is self-evident is that the immediate reaction of 99% of the talking heads in the Western media in response to those events, namely that the Putin regime was on the point of collapse, looks a little suspect.

It makes more sense to keep an open mind on the above issue.

Meanwhile, it is worth noting that Russian GDP per capita was US$1,902 when Putin came to power in 2000 at a time when the Russian state was on the point of collapse and it is now an estimated US$14,404.

While there has been a marked failure to diversify the economy away from its dependence on commodities, the track record is not a total disaster.

China is Shifting to a Multipolar World View

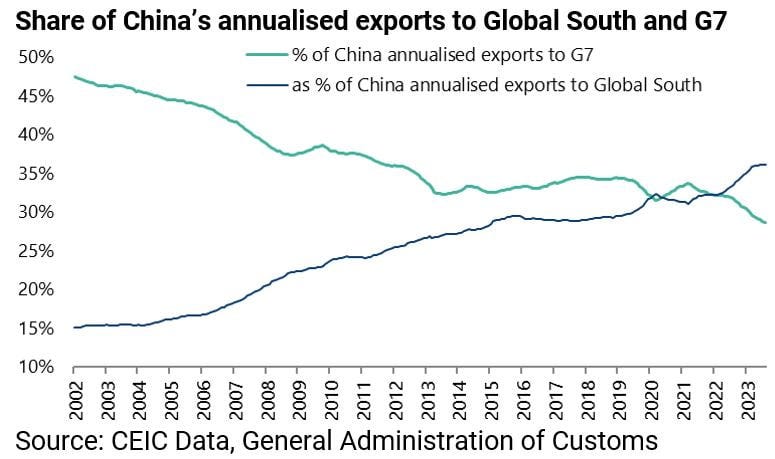

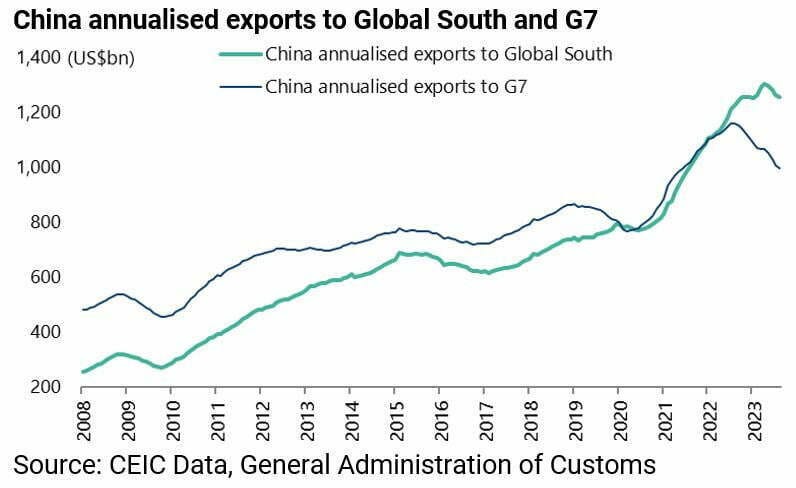

Meanwhile, China’s growing focus on a multipolar world continues to be reflected in the changing profile of its exports.

China’s exports to the Global South now amount to 36% of its annualised total exports, up from 29% in 2018.

By contrast, China’s share of annualised exports to G7 has declined from 34% in 2018 to 29% in August.

This broad definition of the Global South includes Asean, Latin America, Africa, India, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, UAE and Turkey.