The US is Now One Big Bet on AI

Author: Chris Wood

“The US is now one big bet on AI”. This was the headline in an article in the Financial Times last quarter (see Financial Times article: “The US is now one big bet on AI” by Ruchir Sharma, 6 October 2025). This writer could not agree more.

The stampede to invest in AI is one of the most remarkable frenzies ever seen.

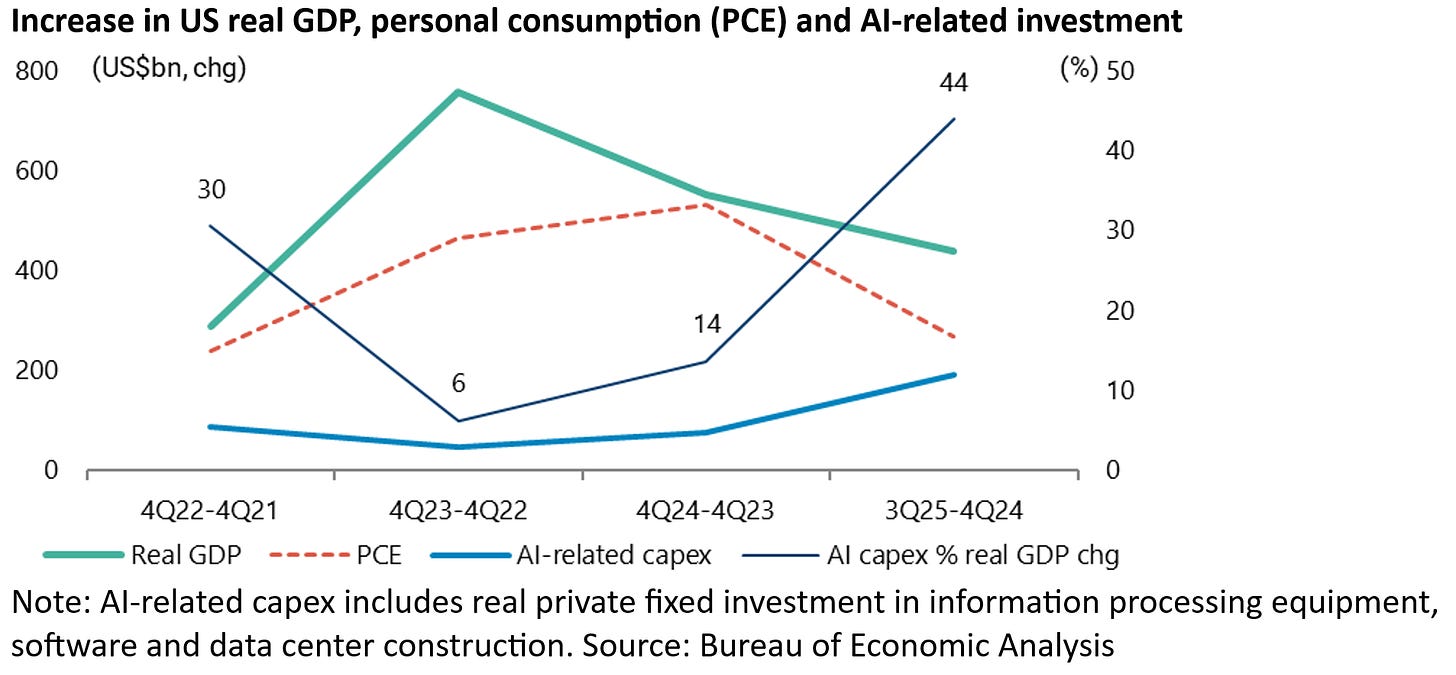

Indeed, AI capex was the main driver of US economic growth last year after personal consumption, based on national accounts data.

US real GDP rose by US$438bn or an annualised 2.5% in the first three quarters of 2025. While real personal consumption and real AI-related fixed investment, including private investment in information processing equipment, software and data center construction, increased by US$268bn and US$193bn respectively over the same period, or an annualised 2.2% and 19.8%.

As a result, real AI-related investment contributed to 44% of the increase in real GDP in the first three quarters of 2025, compared with 61% from real personal consumption.

The AI capex arms race is now three years old.

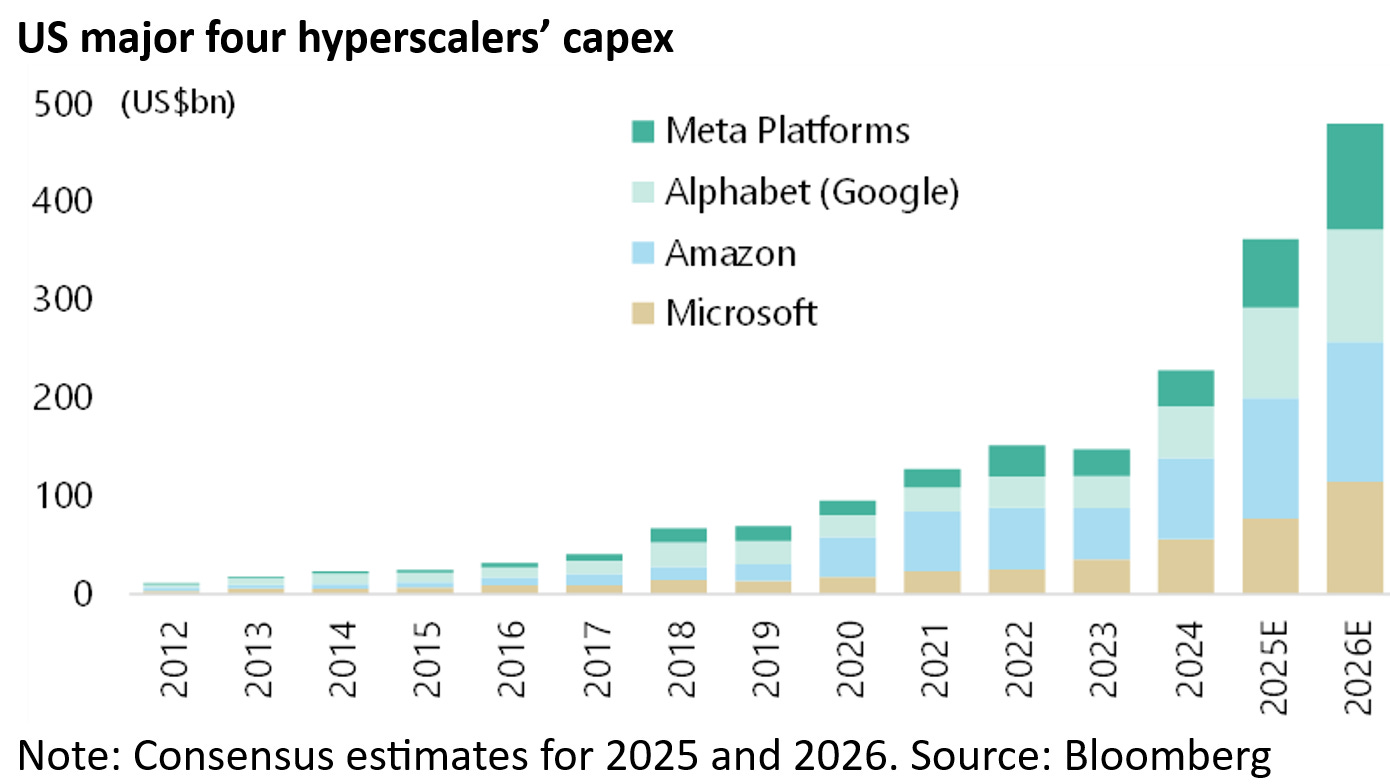

All that spending, running at an estimated US$360bn last year for the four major hyperscalers and a forecast US$480bn this year (see following chart), is based on the premise that OpenAI and others will be able to monetise so-called large language models (LLMs).

Yet in recent months, a MIT study, a FT survey of large companies and a recent Bain analysis have all come to the conclusion that corporates have yet to find any commercially powerful use cases for GenAI.

The MIT study, published in August, found that 95% of “enterprise generative AI (GenAI) pilots” have failed to deliver any financial returns despite US$30-40bn in investment into GenAI (see MIT NANDA report: “The GenAI Divide: State of AI in Business 2025”, July 2025).

While a Financial Times analysis in September of hundreds of corporate filings and executive transcripts suggests most S&P500 companies are not clear about how AI is changing their businesses for the better (see Financial Times article: “America’s biggest corporations keep talking about AI but struggle to explain the upsides”, 24 September 2025).

Then Bain’s sixth annual Global Technology Report published in September estimated that the US$500bn of annual capex spending, which it estimates is the amount needed to fund the necessary data center related infrastructure by 2030, will require US$2tn in annual revenue to earn an adequate return on that investment.

Yet the current estimates of the revenues being generated by AI range from only US$40bn to US$250bn (see Bain & Company report: “Technology Report 2025: AI leaders are extending their edge”, 23 September 2025).

As for consumer applications, there remains, so far as this writer can tell, a lack of any killer app in terms of the uses of chatbots.

It is certainly far from clear who, if anyone, is going to be the winner in the US in terms of the race to build large language models and monetise them.

Indeed, there is a growing view that AI could turn out to be much more like the capex intensive airline industry than the winner-takes-all network effect of the Internet economy from which US Big Tech has so benefited.

Certainly, no killer app has yet been developed for the masses in terms of the practical application of AI.

Rather, this is an area which looks increasingly commoditised with a lack of product differentiation between different providers.

LLM Advancement Certainly Seems to be Slowing

Meanwhile, as the AI capex numbers are getting bigger, the improvements in the LLMs are only seemingly getting marginally better.

OpenAI’s release of ChatGPT-5 in August was widely viewed as an incremental improvement, not the game-changing moment many expected.

But new AI models ChatGPT-4 and ChatGPT-5 cost significantly more than their predecessors to train, often 3 to 5 times the cost of the predecessor.

The other point often ignored is that most of the AI equipment, especially the chips, do not last forever. While the fiber cables laid during the dotcom bubble still have their usefulness, Nvidia chips rapidly depreciate in value.

It is highly questionable whether Big Tech’s depreciation schedules reflect this, most particularly following the changes introduced by the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), in terms of spreading out the cost of purchasing chips and related equipment over several years.

Or in other words, US Big Tech is in no hurry to pay for the AI capex in terms of accounting for it.

This writer remains fundamentally sceptical that ever-greater scaling up the large language models will ever lead to Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), as previously discussed here (What If Chinese AI Stocks Are The Better Value, 20 October 2025).

The base case is also that the main players, be they the hyperscalers or OpenAI for that matter, are, in their rush to spend, driven primarily by the fear of missing out (FOMO) on the next big thing rather than on any conviction that large language models can be monetised.

This is on top of the fact that the Big Tech companies have exited their moats and are now competing directly with each other.

Indeed they are draining their moats.

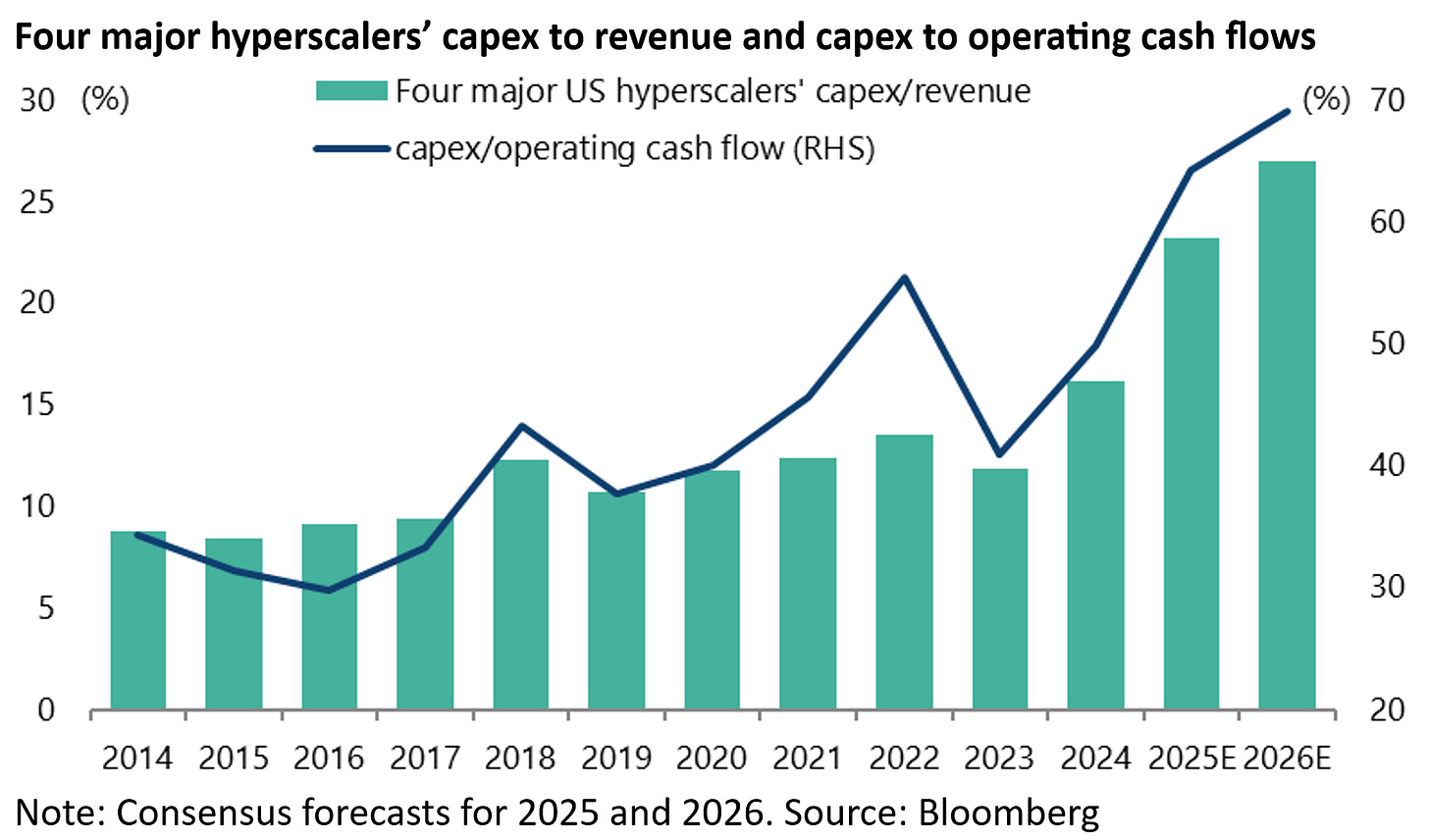

This can be seen in the extent to which capex is rising both as a percentage of revenues and as a percentage of operating cash flow.

The four major hyperscalers’ capex to revenue ratio is projected at 23% in 2025 and 27% this year, or 64% of their combined operating cash flow in 2025 and 69% in 2026, based on consensus forecasts.

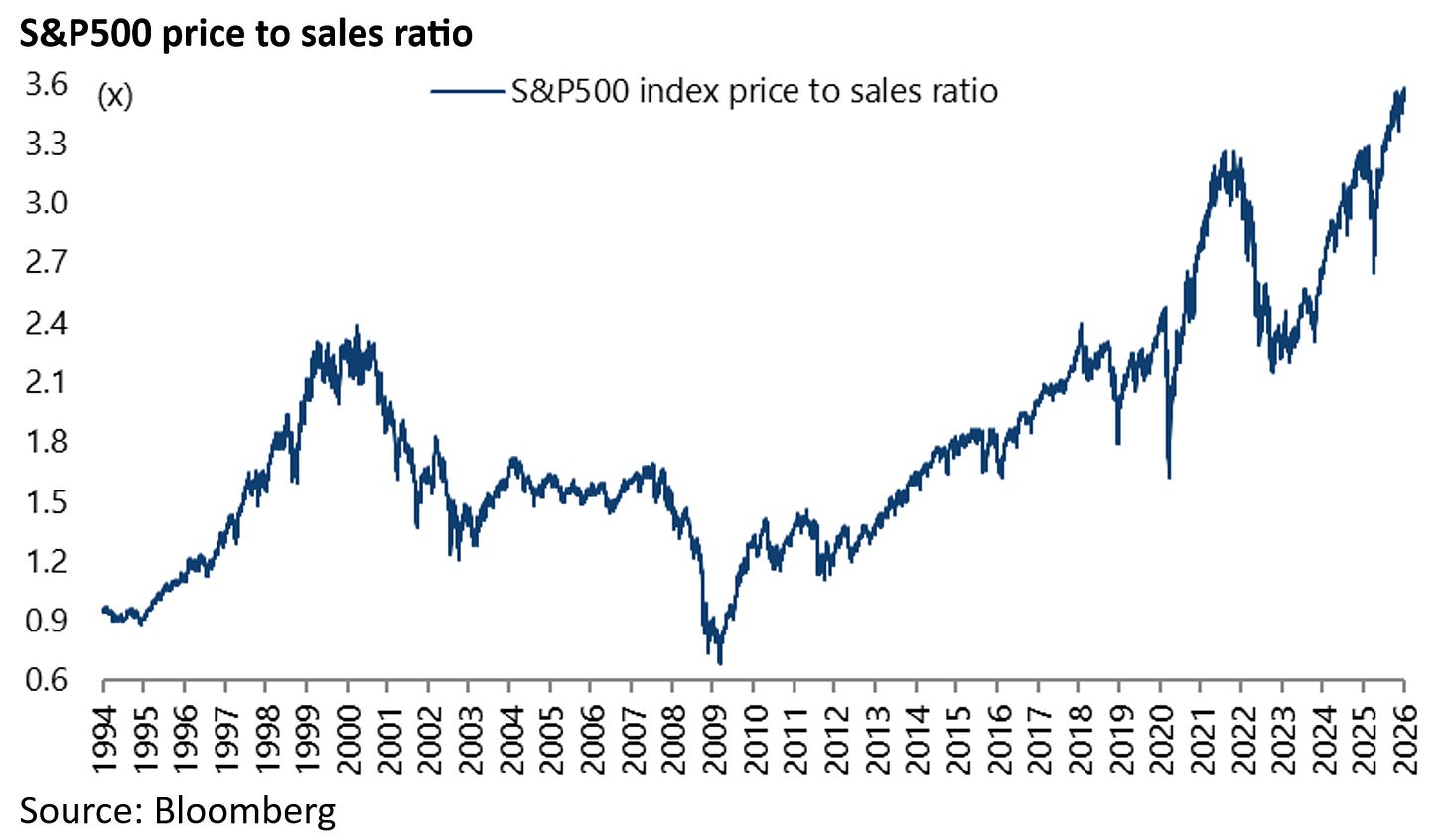

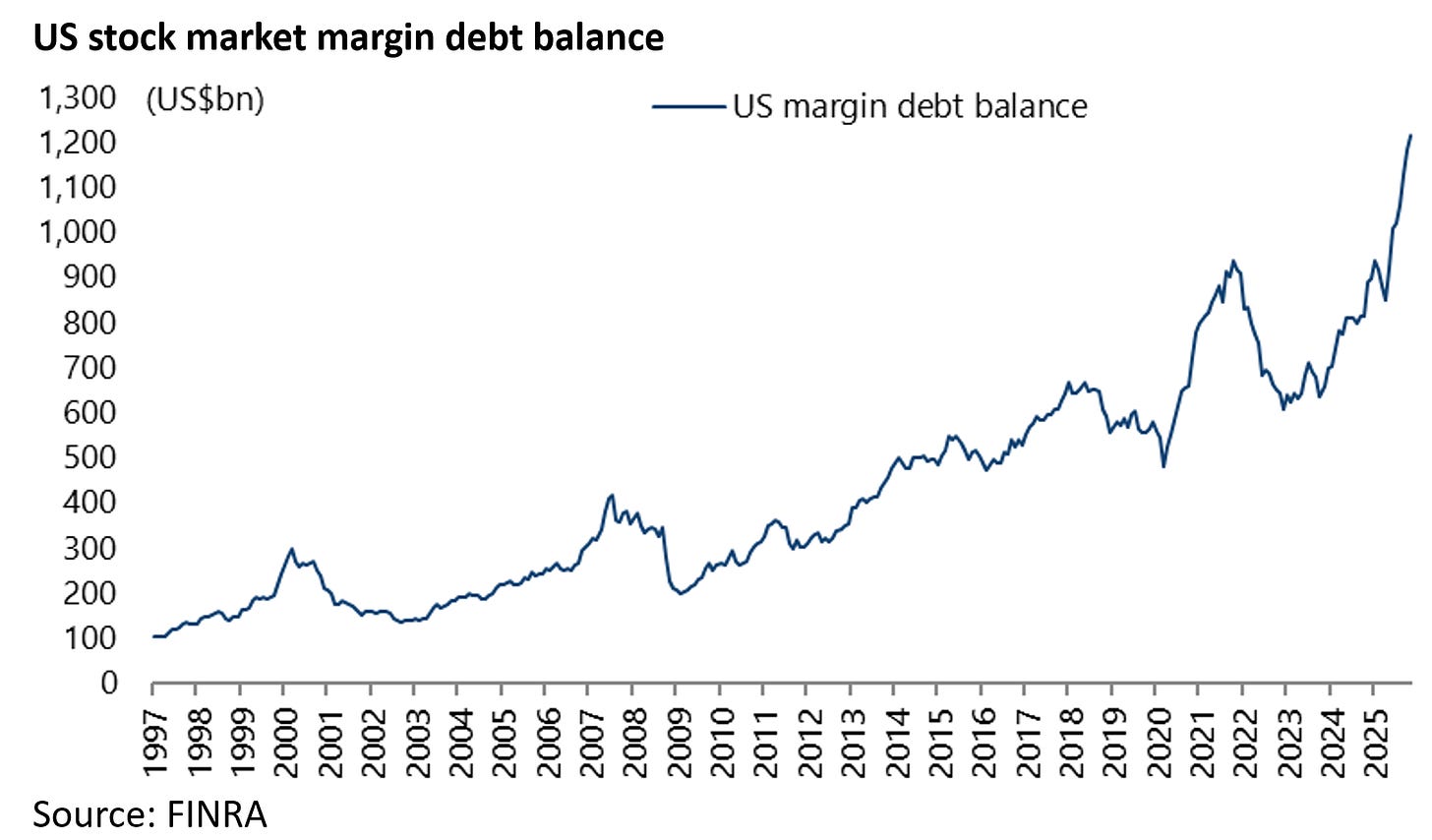

This is the same sort of FOMO which has been driving the ever-more retail-driven US stock market, as reflected in both a record high price to sales ratio and record high stock market margin debt.

The S&P500 price to sales ratio has risen from a recent low of 2.65x in early April 2025 to a record high of 3.58x last Friday.

While US stock market margin debt rose by 36% YoY to a record high of US$1.21tn at the end of November.

All this strongly suggests that markets are much nearer to the end of the AI mania than to the beginning of it or, in other words, based on the Nasdaq Internet-driven boom bust, much nearer to March 2000 than 1995.

It is also the case that, at the end of the day, the high capex budgets of the likes of Meta and Alphabet are being funded by advertising revenues and advertising is cyclical.

Yet with an estimated nearly 50% of consumption accounted for by the top 10% of households, the US economy is now increasingly geared to the US stock market given the wealth effect generated and the US stock market is, more or less, all about AI in terms of the market leadership with about 45% of the gains in the S&P500 since the beginning of 2023 still accounted for by Nvidia and the four hyperscalers.

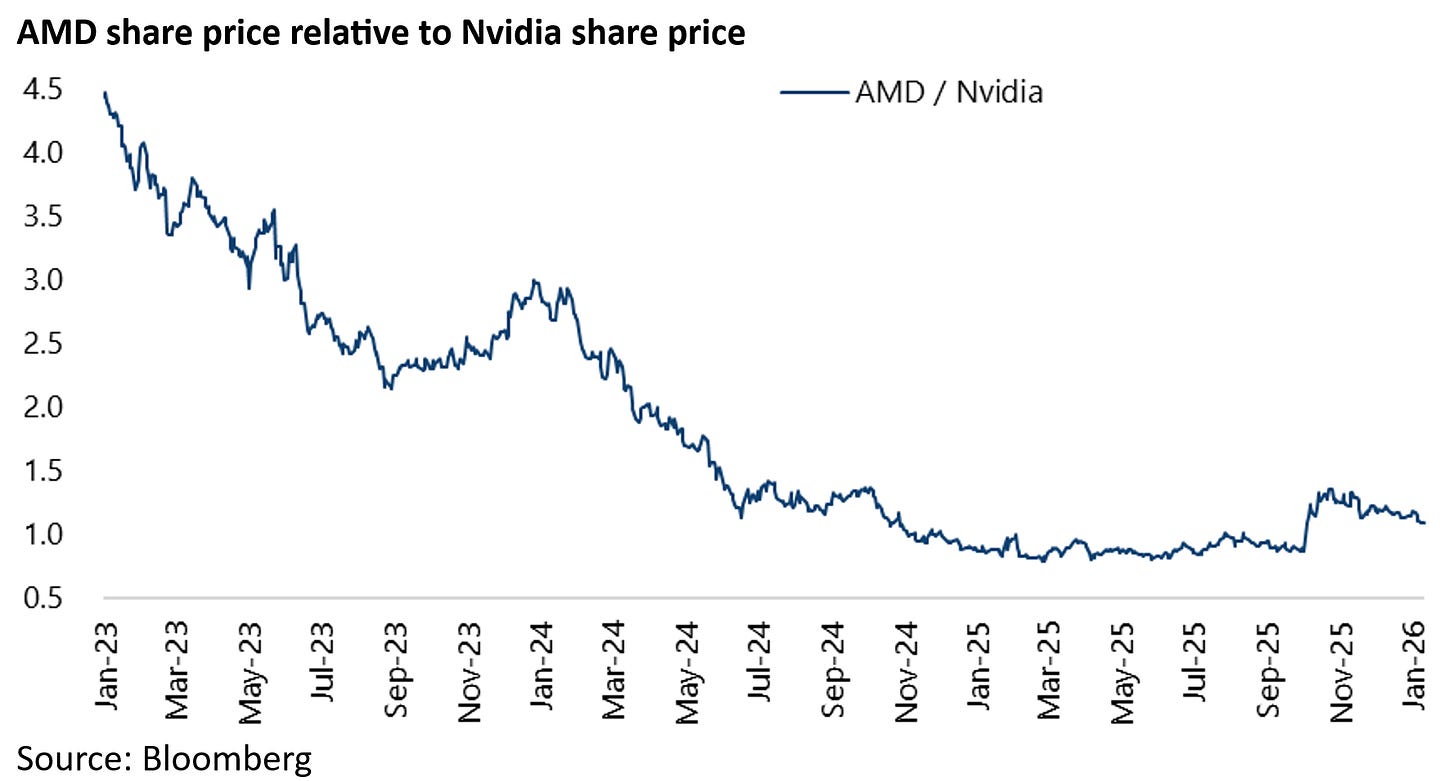

Meanwhile, it is further the case that AMD suddenly playing catch up, in terms of share price performance, with its chief rival Nvidia, is almost what had to happen before AI mania peaks in stock market terms.

AMD has outperformed Nvidia by 27% since the beginning of last quarter but has still underperformed by 75% since the beginning of 2023.