The Recession That Never Was

Author: Chris Wood

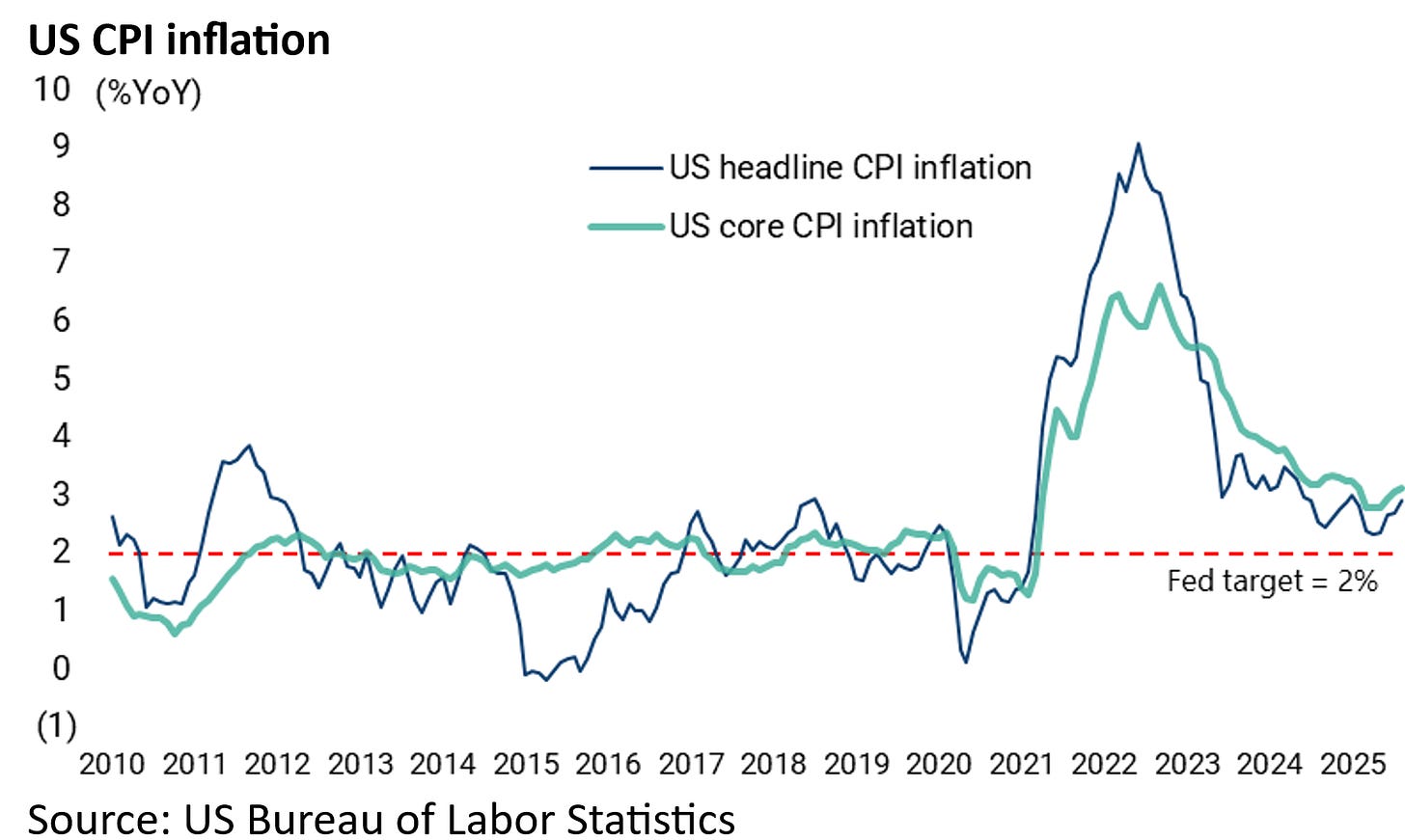

The base case remains for a 25bp rate cut by the Federal Reserve in September (i.e. this Wednesday) even though inflation is still running well above the 2% target based on the latest data.

US headline CPI and core CPI were up 2.9% YoY and 3.1% YoY, respectively, in August.

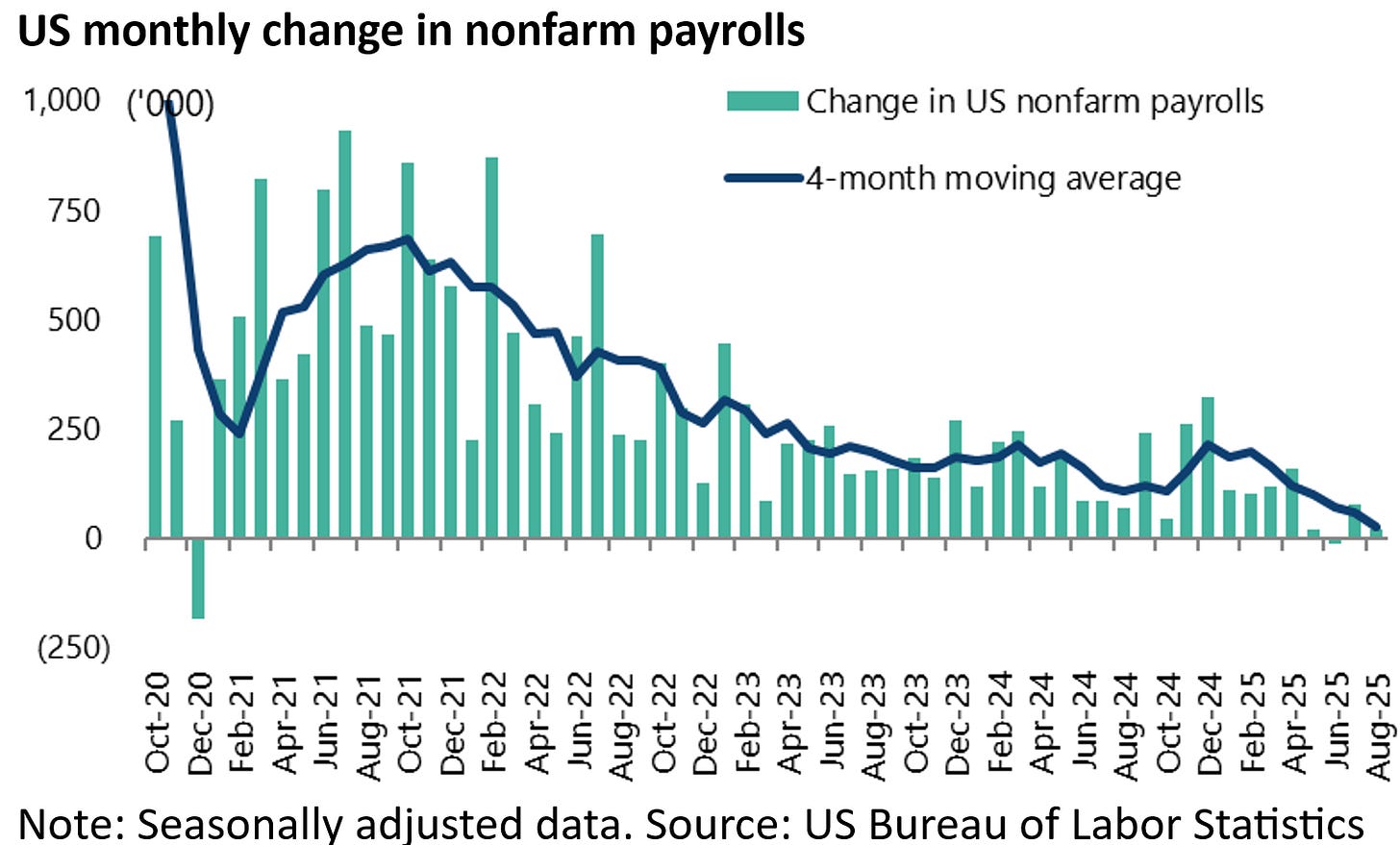

The official reason is, of course, growing evidence of labour market weakness.

The latest monthly US employment data showed that US nonfarm payrolls increased by only 22,000 in August on a seasonally-adjusted basis, well below consensus expectations of 75,000, while the increase in the previous two months was revised down by 21,000 jobs following the 258,000 downward revision in early August.

As a result, US nonfarm payrolls increased by “only” 107,000 jobs in the past four months or an average 26,750 per month, the lowest level since July 2020.

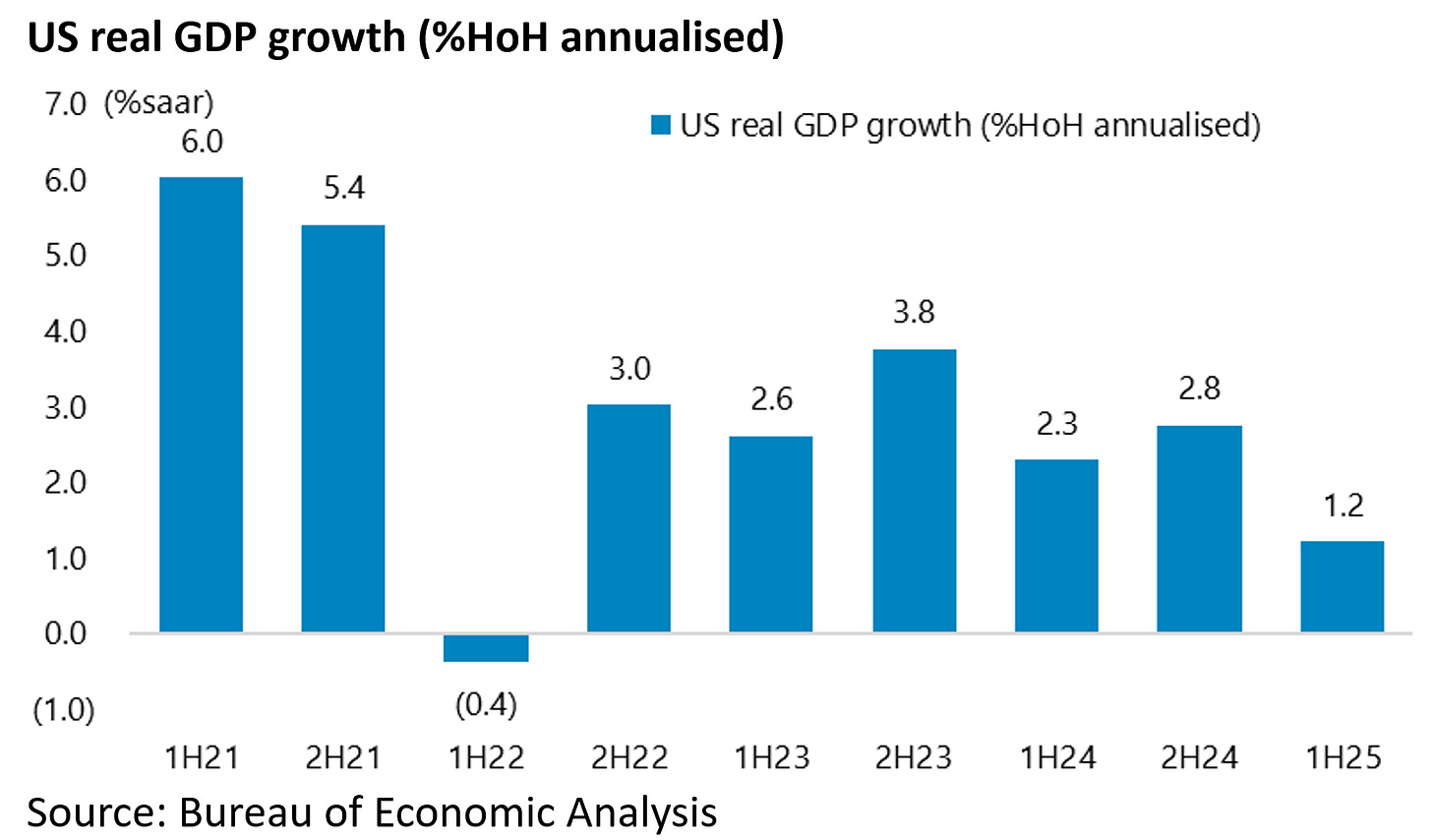

Ex-Tariff GDP Shows US Economy is Slowing

As regards the latest revised GDP data, stripping out the distortion triggered by the tariff agenda in terms of the front loading of imports in the first quarter, the key point is that the growth rate of the US economy has slowed from an annualised 2.8% in the second half of 2024 to an annualised 1.2% in the first half of this year.

Meanwhile, more important for financial markets than the Fed is the continuing calm in the Treasury bond market after the most recent Treasury quarterly refunding announcement in late July has again confirmed the ever growing resort to short-term financing.

The US Treasury announced no change in coupon auction sizes for the coming quarter, while Treasury bill supply is going to continue to increase in the coming weeks.

Clearly, as discussed here previously (see Stablecoins, Bonds & Hyperscalers Oh My!, 24 July 2025), the Trump administration’s strategy is to create growing demand for Treasury bills via the launch of stablecoins.

Tether is already the 18th largest holder of Treasuries if it were a country, holding more than US$127bn in US Treasuries in 2Q25.

Trade Deal with Europe is Far From Set in Stone

Returning to trade and tariff issues, if craven capitulation was the base case it is still a bit shocking to see the extent to which that assumption was confirmed in terms of the details of the agreement announced in late July between the US and the EU with the language, as expected, also seemingly committing the EU to buy US weaponry.

President Donald Trump and a far from comfortable looking European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced on 27 July following a meeting at Trump’s Turnberry golf course in Scotland that the US and EU had agreed to the framework of a trade deal that included a 15% tariff on EU exports to America.

True, that is substantially lower than the threatened 30%. Still the sectoral tariffs on steel, aluminum and copper will for now remain unchanged at 50%.

The White House also stated that, as part of the deal, the EU will purchase US$750bn in US energy and make new investments of US$600bn in the US by 2028. The EU will also purchase “significant amounts” of US military equipment.

As for the EU tariffs on US goods, the EU will remove significant tariffs, including the elimination of all EU tariffs on US industrial goods exported to the EU.

If these are the reported details it should be remembered that, just as in the world of corporate finance a memorandum of understanding does not necessarily constitute a final deal, so the same applies with trade deals, most particularly when the deal consists of quid pro quos which are not directly linked to trade.

Thus, as regards the US$600bn of new investments in the US seemingly committed to by the EU, so far as this writer understands it such a commitment is outside the prerogative of the European Commission which is charged with negotiating trade issues.

Investment targets are more the responsibility of individual countries and ultimately come down to private sector decisions.

It is also the case that both France and Germany were quick to raise concerns over the deal on 28 July. German Chancellor Friedrich Merz said that the agreement would cause “considerable damage” to the German economy.

While French Prime Minister François Bayrou, who has since subsequently resigned, said the deal marked a “dark day” and that the EU had “resigned itself into submission” (see Financial Times article: “Germany and France hit out at EU-US deal”, 29 July 2025).

Still the growing penchant of the 47th US president for such deals, including often getting countries to agree to buy specific amounts of Boeing aircraft, are a sad reflection of the accelerating breakdown of the GATT area which has been beneficial for so many.

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade dates back to October 1947 when it was signed by 23 countries in Geneva.

Cracks Forming in The Japan Trade Deal

Returning to the issue that a deal is not a deal until fully confirmed, it is also the case that cracks also surfaced in the supposed trade deal with Japan also announced with fanfare in late July.

The normally polite Japanese pushed back against the notion peddled by US Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick that Japan would finance US$550bn worth of investments in US strategic sectors and that the profits from these investments would be split 90% to US taxpayers and only 10% to the Japanese.

Still if the deal now renegotiated in September looks slightly less one sided, it remains unattractive from a Japanese standpoint.

The problem is that the negotiations have encountered an ongoing gulf between what the Japanese side believe they have agreed and what President Trump has stated has been agreed.

In the pursuit of this negotiation the main Japanese negotiator, Minister in charge of Economic Revitalization Ryosei Akazawa, has visited Washington no less than ten times since April. Still the US president finally signed an executive order on 4 September making a 15% tariff rate official, effective 16 September, which means Japanese automakers will not have to pay the previously threatened 27.5%.

But the price paid for the US agreeing to the lower tariff remains a commitment by Japan to invest US$550bn into the US.

On this point, there remains a lot of room for continuing disagreement.

The Japanese view seems to be that the US$550bn includes loan guarantees from Japanese public financial institutions whereas this is most unlikely to be the interpretation in Washington.

Indeed Trade Secretary Howard Lutnick said on US TV on 5 September that, in return for lower tariffs, the Japanese “have given President Trump US$550bn for President Trump to direct where and how he wants it invested in America”.

Then there is also the issue, still seemingly to be agreed, of how the profits on any such investments, assuming there are any, are to be divided.

Remember that the Donald’s original request was for a 90/10 split.

Apparently, the memorandum of understanding signed on 4 September by Lutnick and Akazawa stated that Japan and America will evenly split the cash flow generated until Japan’s investment is paid off, at which point the US will take 90% of the proceeds and Japan 10% (see Financial Times article: “Trump to direct Japan’s trade deal cash”, 9 September 2025).

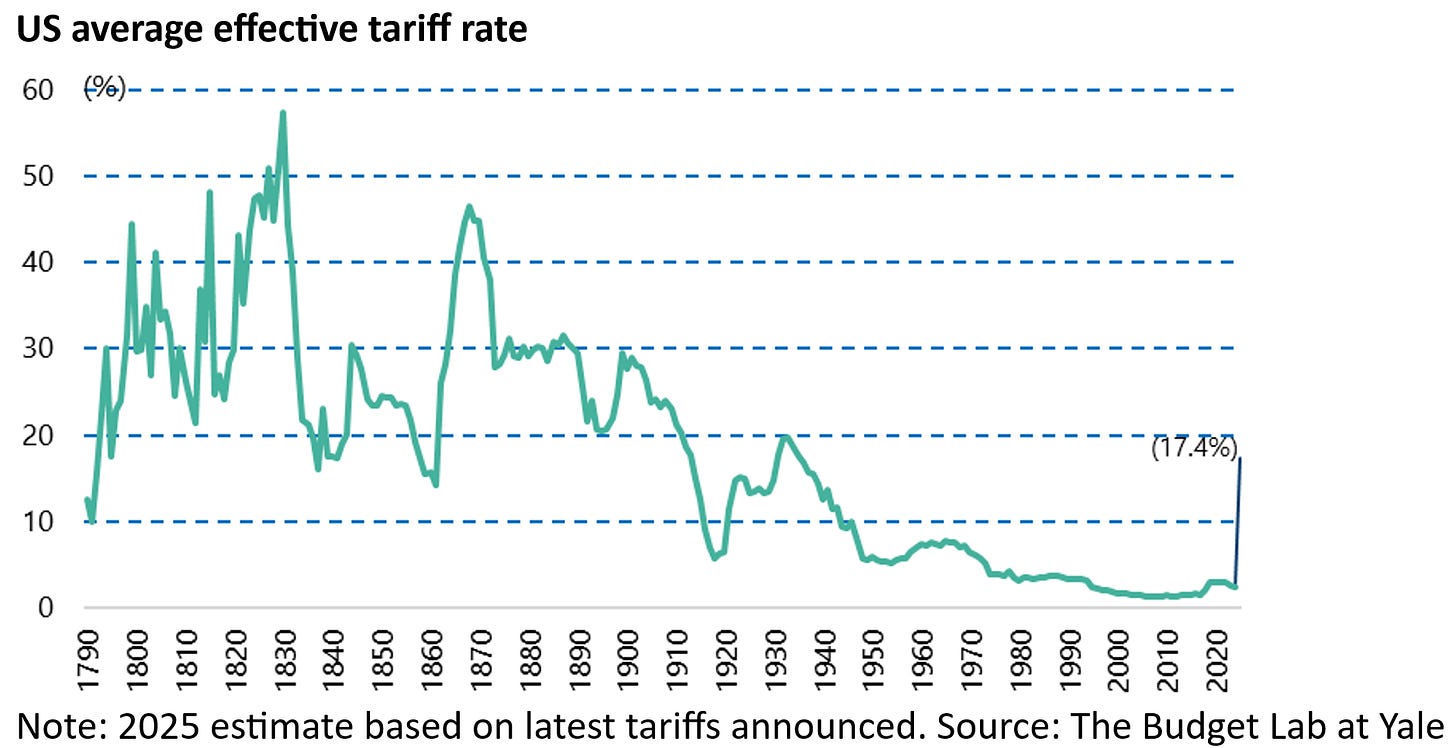

Fundamentally, the base case of this writer remains that tariffs are bad for everybody as taught in classical economics.

Is Another Bull Market Beginning in the US?

Still there is a narrative whereby America emerges as the least bad off from the tariff agenda.

The Yale Budget Lab now estimates the average tariff as a result of the recent announcements at 17.4%, the highest level since 1935.

First, while it is too early to tell how much prices will rise for US consumers the positive consequence of OBBBA, in terms of corporate tax cuts and the like, may mean that companies can take some of the pain of the tariff increase, at least initially.

Second, increased capital investment in America and increased purchases of US weaponry remain cyclical positives.

In this respect, it is worth highlighting again the increased investment in US factories in recent years, which had its origins in the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act and CHIPS and Science Act in 2022, should now be further stimulated by Trump’s agenda with the differences being that Joe Biden offered carrots in the form of subsidies whereas Trump has threatened sticks in the shape of punitive tariffs.

Thus, private construction spending for manufacturing facilities has more than doubled from a seasonally adjusted annual rate of US$98bn in January 2022 to US$239bn in June 2024 and US$222bn in July 2025, with construction spending for computer, electronic and electrical manufacturing up almost fivefold from a seasonally adjusted annual rate of US$26bn in January 2022 to US$126bn in July 2024 and US$108bn in July 2025.

Still there has yet to be a corresponding pickup in imports of industrial machinery.

US imports of machinery, excluding transport equipment, have risen by “only” 31% from an annualised US$819bn in 2021 to US$1.086tn in the 12 months to July 2025.

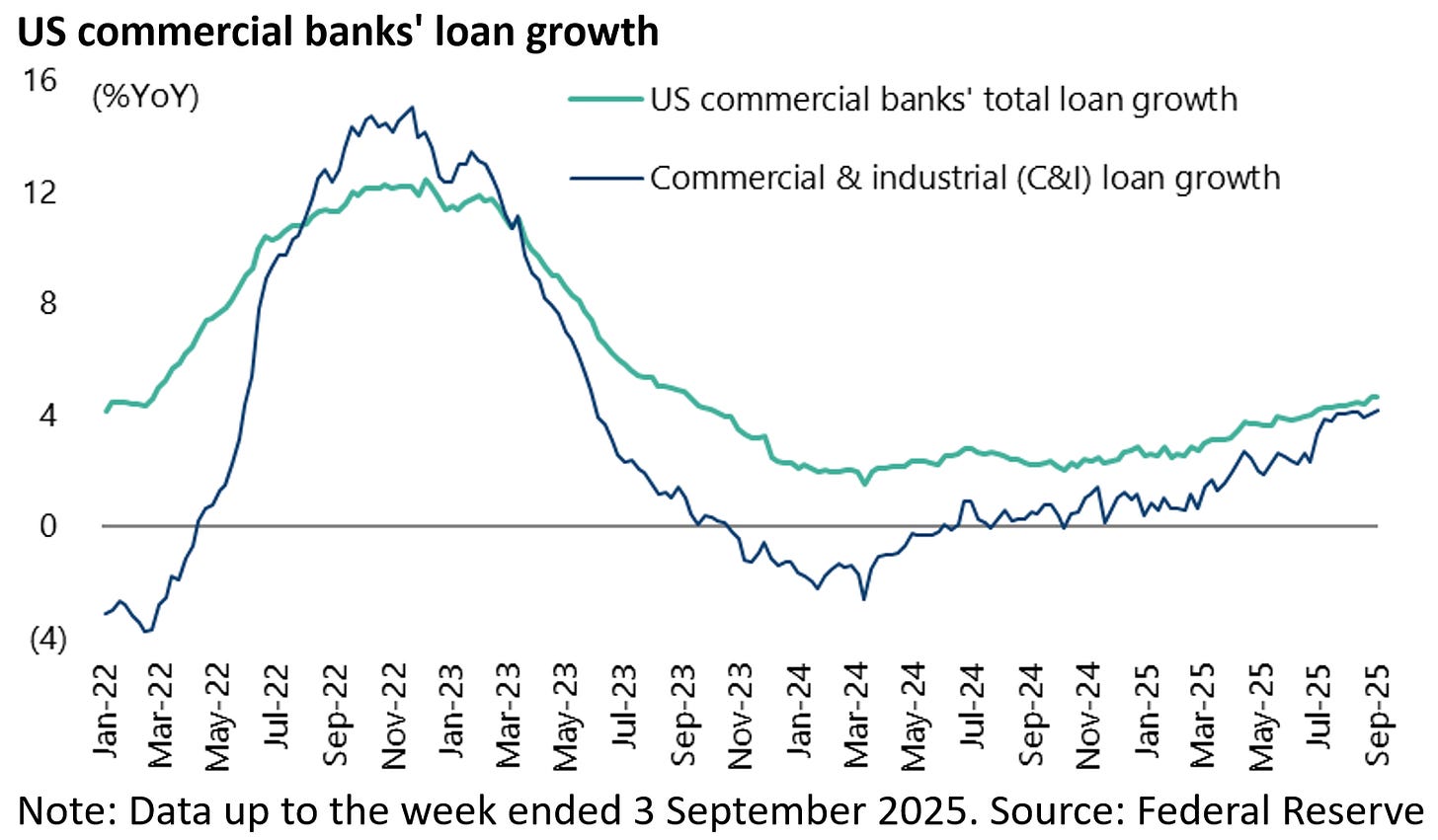

For such reasons it is entirely possible to make the argument that the US economy could be in the early days of a new cyclical rebound, a point also suggested by the trend in commercial bank loan growth.

US commercial banks’ total loan growth has risen from 1.5% YoY in mid-March 2024 to 4.6% YoY in early September 2025, while commercial and industrial (C&I) loan growth is up from a negative 2.6% YoY to 4.1% YoY over the same period.