The Pitfalls of Owning US Debt

Author: Chris Wood

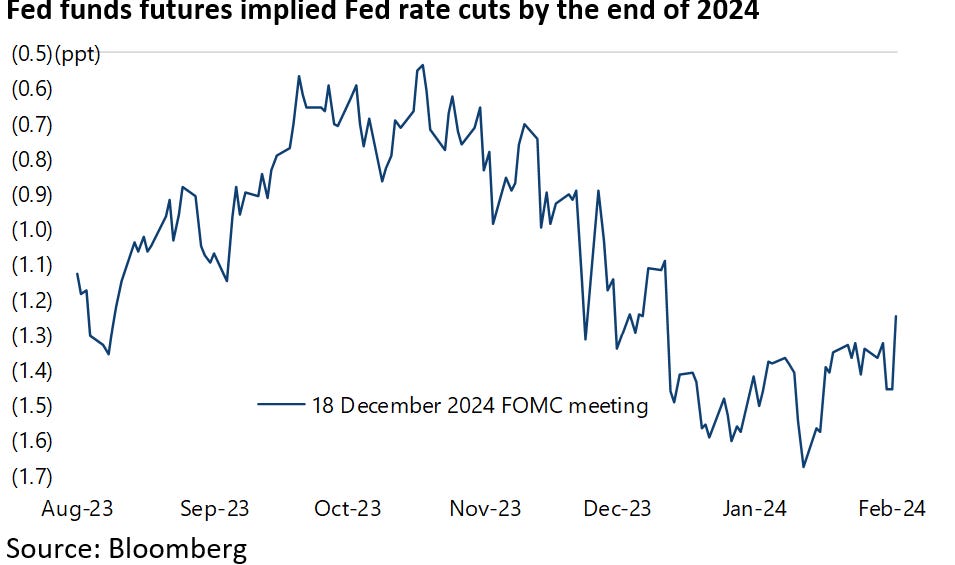

Jerome Powell stepped back from his uber dovish tone in December at the January FOMC meeting last week saying at the post-meeting press conference:

I don't think it's likely that the Committee will reach a level of confidence (to cut rates) by the time of the March meeting to identify March as the time to do that. But that's to be seen.

If that is the latest message from the Fed chairman, as regards his unexpected early Christmas present to markets at the December FOMC meeting the issue still lingers as to what exactly then motivated Powell who has now further cemented his well-earned reputation for pivots.

After all, as the Wall Street Journal noted in its report of the December meeting, it was only two weeks prior at an appearance at Spelman College in Atlanta that Powell said it was too soon to speculate about when lower rates might be appropriate (see Wall Street Journal article: “Fed Begins Pivot Toward Lowering Rates as Inflation Declines”, 13 December 2023).

Indeed, the whole episode has served to remind this writer of Powell’s most famous quote of all when he said in June 2020 that the Fed was “not even thinking about thinking about raising interest rates”.

While inflation had undoubtedly slowed going into the December meeting the data, be it related to inflation or employment, had not really supported such a change in rhetorical stance.

There are three plausible explanations for the changed language in December.

The first is that the Fed was aware of data not yet published which has caused governors to become more concerned about the economy and in particular the labour market.

The second is that the Fed chairman risked losing the support of the committee and, in the spirit of maintaining a collective consensus, decided to side more with the majority opinion.

There is, after all, a perfectly legitimate dovish argument that monetary policy works with a lag and that the labour market is a lagging indicator.

The third explanation is that Powell’s change of language was driven by the presidential election cycle and the dramatic ongoing slump in Joe Biden’s approval rating, a trend which has continued since.

The latest ABC News/Ipsos poll conducted on 4-8 January showed that Biden’s approval rating has declined to a new low of 33%, down from 37% in September 2023.

Of the above three explanations, the most persuasive to this writer is the political one.

Powell may be a signed-up Republican.

But he is the epitome of the country club Republicans who have lost out in the party as a consequence of the rise of Donald Trump and what might be termed Trumpism, which is now the dominant strand in the GOP, as can be seen in Trump’s still commanding lead in the race to be the Republican presidential candidate.

The Shifting Views of Fed Chair Jerome Powell

Born and bred in the Washington area and educated at Georgetown Prep, Powell is a classic Washington insider with well-developed political antennae.

On this point, this writer read recently a highly recommended book published in 2022 (The Lords of Easy Money: How the Federal Reserve Broke the American Economy by Christopher Leonard, Simon & Schuster, January 2022).

The book is essentially a history of the QE zero rate era.

It contains, among other things, interesting insights into the politics of the Fed.

It relates how Powell, as an orthodox Republican, when he started as a Fed governor in 2012 had, initially, an entirely laudable desire to promote the normalisation of monetary policy because of his concern about the unintended distorting consequences of quantitative easing and zero rates, such as soaring inequality via asset price inflation.

However, he never cast a dissenting vote while, as the book notes, Powell’s star started to rise within the Fed when from 2015 on he began to embrace the policies he previously criticised.

Appointed by Trump as Fed chairman in 2018, the book also relates how Powell’s desire to maintain close relationships with both sides of the political aisle in Washington prompted him to meet with 56 lawmakers on Capitol Hill in his first eight months in the job, with the visits spread more or less equally between both major parties.

By contrast, Janet Yellen, an altogether more scrappy, less consensus seeking personality, visited with only 13 during her first eight months as Fed chair.

This fact is recorded simply to highlight that Powell is not operating in a political vacuum.

Meanwhile, it is obvious that the Democratic Party must be increasingly concerned about Biden’s slumping approval ratings despite a strong economy, seemingly healthy labour market, and booming stock market, albeit one where the gains have been narrowly concentrated.

For the polls are indicating that if an election is held today Trump is the likely winner

This will also be a concern to the country club Republicans, such as members of the Trump-hating Lincoln Group, for whom the essential message is anyone but Trump.

From a market standpoint, the Fed’s seeming switch has been clearly, first and foremost, equity bullish and US dollar bearish.

But despite the Treasury bond market’s further rally following the December Fed meeting, it is long-term bearish for Treasury bonds, which this writer continues to believe are in a structural bear market.

On the latter point, it is worth highlighting again the federal government’s rising debt servicing costs.

US annualised net interest payments as a percentage of federal government receipts rose to 16.2% in December, the highest level since March 1997.

Long Term Investors Should Avoid Owning US Government Debt

With neither political party likely to embrace meaningful fiscal discipline whatever the outcome of this year’s presidential election, long-term-orientated fixed income investors in government bonds should continue to avoid exposure to US Treasuries and, indeed, G7 government bonds in general, given it is only a matter of time before the likes of the ECB and the Bank of England change language also.

Instead, fixed income investors should stay invested in local currency emerging market government bonds.

They have already outperformed dramatically in US dollar terms since March 2020 when US M2 growth exploded and during a period when the US dollar has mostly been strong.

They are likely to outperform even more in US dollar terms when the dollar is weak.

Thus, the Bloomberg EM local currency government bond index has outperformed the Bloomberg global government bond index by 30% since late March 2020, while the US dollar index is up 16% from the low in early January 2021.