Small Business, Not the Bond Market, Will Cause the Next Recession

Author: Chris Wood

A counterintuitive in terms of the rising recession talk in recent months has been the ongoing rise in US bank credit growth.

Still there are now clear signs that US bank credit has begun to slow.

US commercial banks’ total loan growth has decelerated from 12.5% YoY in early December to 9.1% YoY in the week ended 12 April, while commercial and industrial (C&I) loan growth is down from 15.6% YoY in late November to 8.1% YoY.

This is interesting, most particularly given the significant rise in the percentage of banks reporting weakening loan demand on the part of both consumers and corporates.

The Federal Reserve’s January Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey shows that a net 37.8% of US banks reported weaker demand for business loans over the past three months, the highest level since October 2020, up from 31.3% in October and 4.3% in July.

While a net 64.5% of US banks reported weaker demand for household loans, up from 36.8% in October and the highest level since October 2008.

Clearly, this survey was carried out before the recent failure of Silicon Valley Bank and the related knock on ripple effects on other US regional banks.

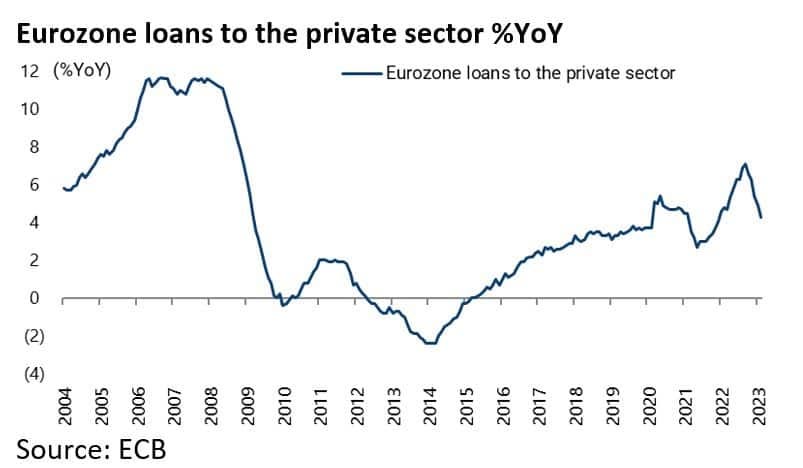

While the US data is clearly the key driver of global market sentiment, the same trend can be seen in the Eurozone, in terms of both a slowdown in loan growth and surveys indicating weakening loan demand.

Eurozone bank loans to the private sector rose by 4.3% YoY in February, down from 7.1% YoY in September.

While the latest ECB Bank Lending Survey also shows that a net 74% of Eurozone banks reported weaker loan demand for mortgages in 4Q22, the highest level since the survey data began in 4Q02.

A net 11% of banks also reported weaker loan demand for enterprises in 4Q22, compared with a net 13% of banks reporting stronger loan demand in 3Q22.

Meanwhile a slowdown in credit growth in America should not be a surprise given 475bp of rate hikes so far in this Fed tightening cycle.

The lags in this tightening cycle are longer than normal

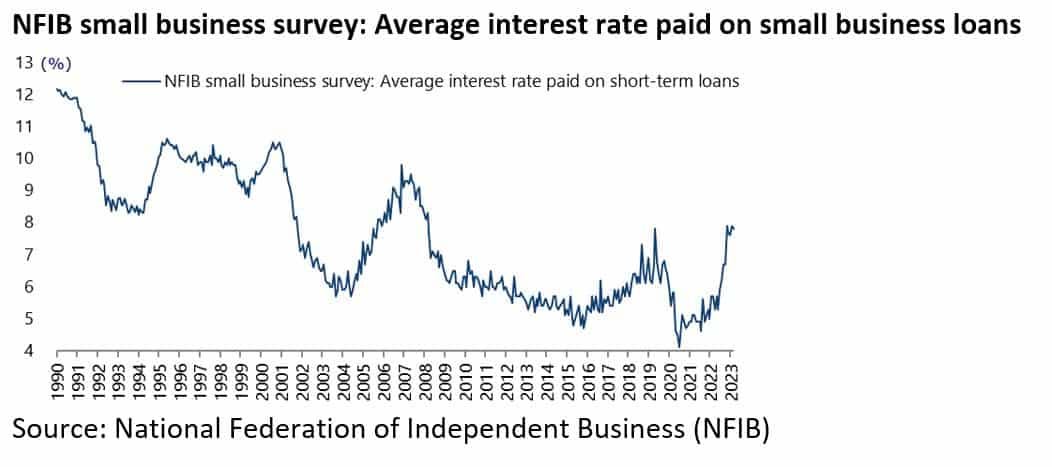

One reason for that is the increased importance of small businesses which are much more sensitive to short-term interest rates than to financial conditions as reflected in credit spreads and the like.

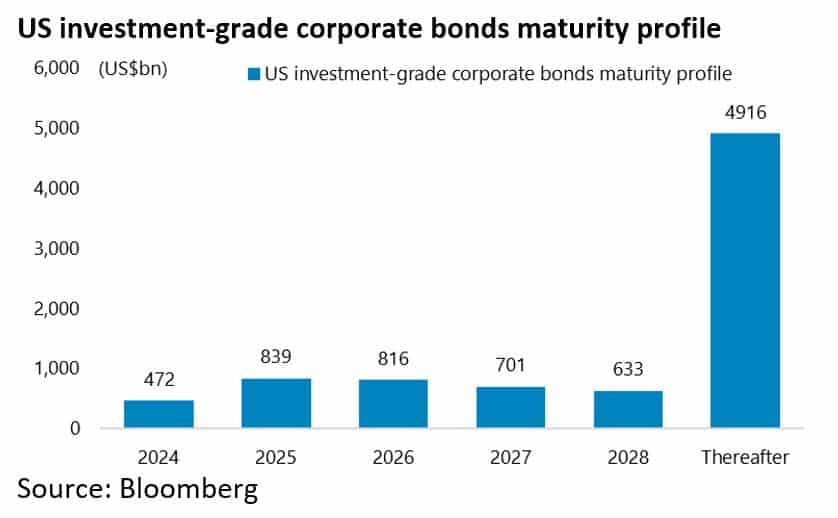

In this respect, it should be remembered that many US corporates, with access to the bond market, have been able to term out their debt.

On this point, US$3.5tn of US investment-grade corporate bonds are due to mature in the next five years, while US$4.9tn will only mature after 2028.

Returning to the theme of the importance of the small business sector in this cycle, small businesses accounted for nearly 79% of all job openings and more than 90% of the post-pandemic increase in labour demand.

It should be noted that the cutoff for such businesses in the chart below is a payroll of 250 employees.

The issue here is clearly that small businesses borrow from banks with floating rate loans which are currently priced at 7.8%.

It would be very strange if the rising cost of money did not begin to show up in profit margin pressures by the second half of this year, most particularly in a macro context of declining nominal GDP growth.

Nominal GDP growth has already slowed from 12.2% YoY in 4Q21 to 7.3% YoY in 4Q22.

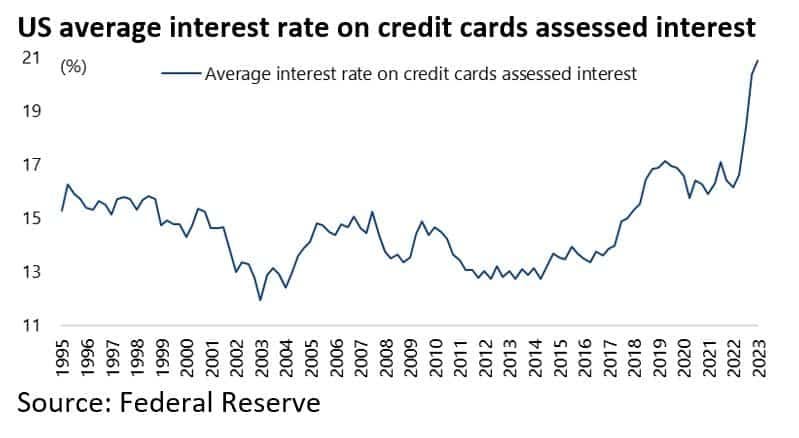

The US Consumer Still has Excess COVID Money

The same logic also applies to the American consumer where the average interest rate charged on unpaid credit card balances, totaling US$986bn at the end of 4Q22, was 20.9% in 1Q23.

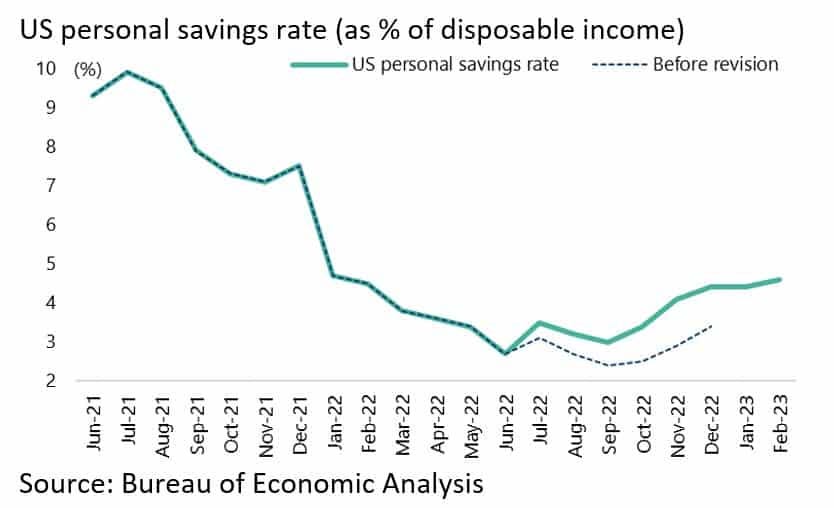

Still it also should be pointed out that the upward revisions to US savings rate data announced in late February mean that American households have used up less of their excess savings, paid out via transfer payments during the pandemic, than previously thought.

The average personal savings rate for the second half of 2022 has been revised up from 2.8% to 3.6% of disposable income, with the December savings rate revised up from 3.4% to 4.4%. It has since risen to 4.6% in February.

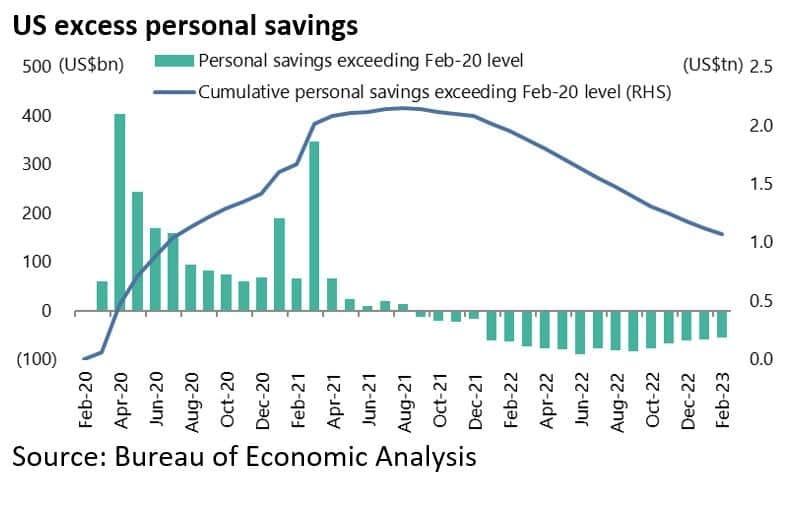

Remember so-called US excess personal savings, measured for this purpose as the gap between actual monthly personal savings and the pre-pandemic level of an annualised US$1.58tn in February 2020, have turned negative since September 2021, meaning that Americans have since then started to spend their excess savings accumulated during the pandemic.

As a result of the latest revisions, the average monthly amount spent on such cumulative excess savings in the second half of 2022 has been revised down from US$88bn to US$75bn.

Indeed Americans spent “only” US$55bn of their cumulative excess savings in February, down from US$90bn in June 2022.

Meanwhile, the cumulative excess savings have now declined by US$1.084tn or 50% from the peak of US$2.152tn in August 2021 to US$1.068tn in February.

So the clock is still ticking in terms of the lagged impact of monetary tightening and the related ongoing depletion of those excess savings.

In this respect, as regards the traditional lags in monetary policy, the Fed only began tightening 13 months ago.

Private Debt Price Discovery Will Take Time

Meanwhile the trend in bank credit growth could signal the all-important inflection point though, as previously noted here (“Are Leveraged Loans This Cycle’s Ticking Time Bomb?”, 27 July 2022), the weird thing about the recent cycle is that the commercial banking system has not funded the boom area, namely private equity.

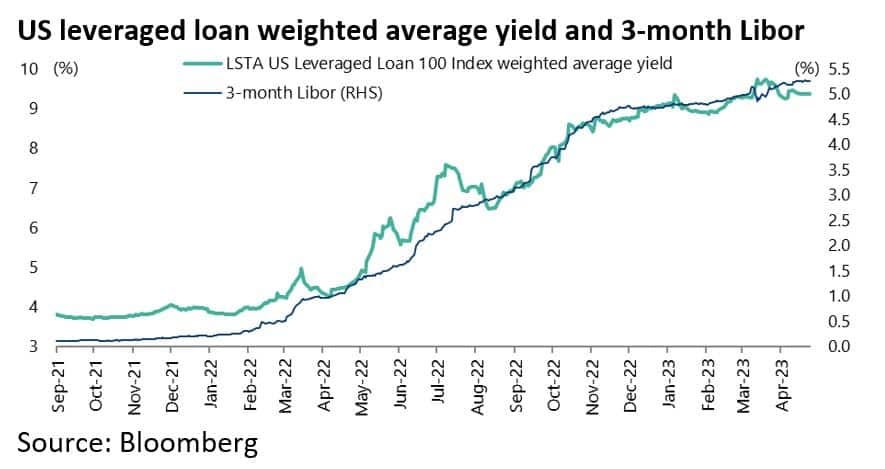

That has been financed primarily by the private lending market via leveraged loans, which are priced with reference to Libor which has risen from 0.92% to 5.26% since mid-March 2022 when the Fed commenced tightening.

And no one involved in the world of private equity, be they lenders, managers or investors, is in any hurry to accelerate price discovery.

Indeed, their incentive is to delay price discovery for as long as possible.