Key Takeaways From Our Recent Trip to Beijing

Author: Chris Wood

Two things are clear from a recent visit to the China capital.

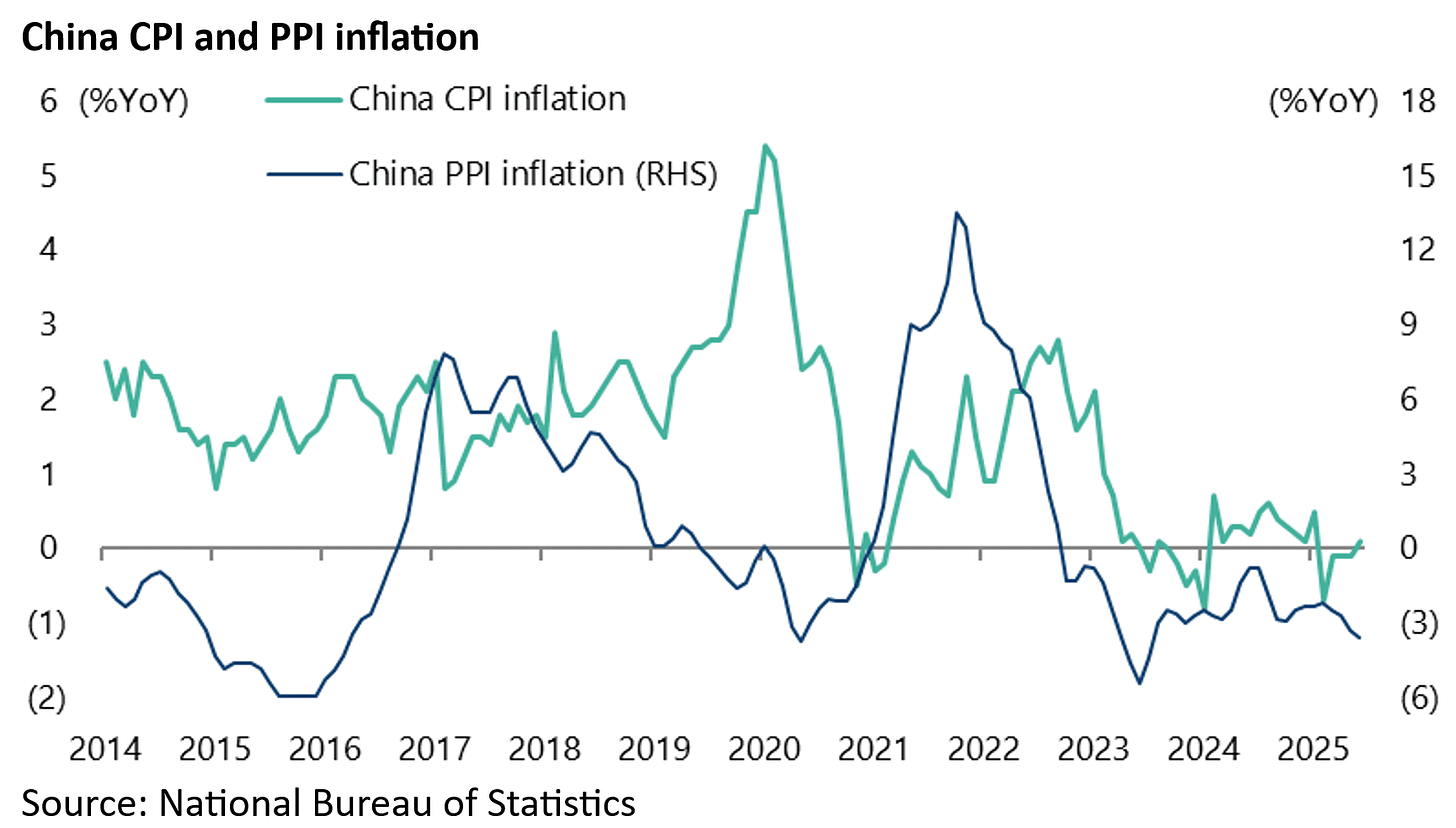

First, there is no sign that deflation is ending.

Second, President Xi Jinping’s strategy of “boosting new productive forces” has worked almost too well in the sense that this is a supply focused strategy and therefore is one key reason for the continuing deflationary trend.

Still there is a positive side to the deflation in the sense that it is in part productivity-enhancing driven, as perhaps best reflected in the DeepSeek moment in January.

The focus in China right now is all about how an extremely cheap open-source DeepSeek is going to trigger a whole new wave of AI applications, many of which have the potential to be commercially viable and trigger new sources of demand.

AI applications in healthcare are a good example.

So, the focus in China on AI is on cheap and practical applications.

Whereas in America the likes of OpenAI and the hyperscalers are still seeking to build superior proprietary large language models (LLMs) as they pursue the goal of AGI (Artificial General Intelligence).

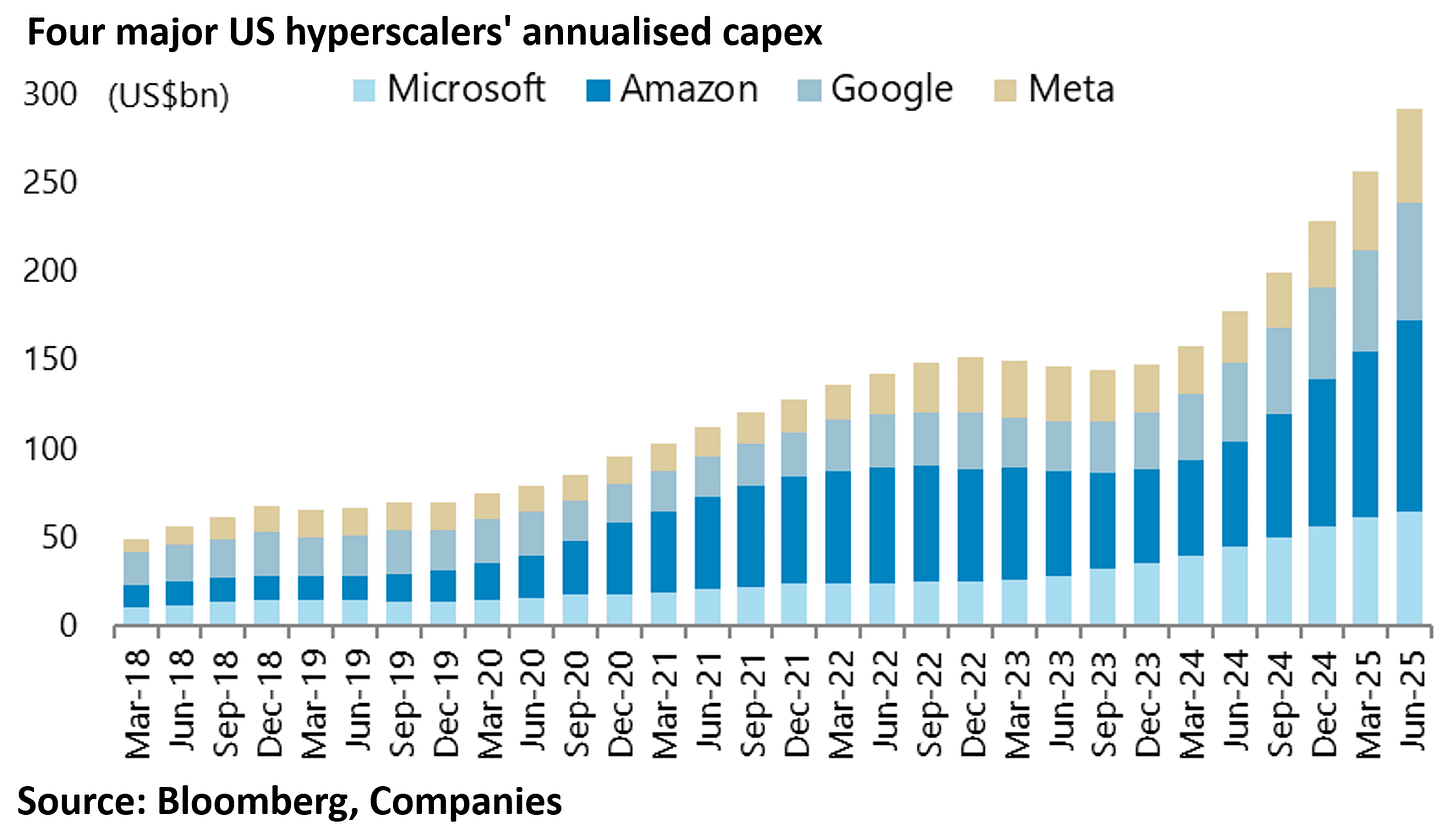

Hence the dramatic surge in capex by the hyperscalers.

The four major US hyperscalers’ capex rose by 55% YoY from US$147bn in 2023 to US$228bn in 2024 and was up 65% YoY to an annualised US$292bn in the four quarters to 2Q25.

Deflationary Forces are Offsetting AI Upside

If this is the positive side of the China deflation, there is also the negative aspect of deflation as reflected in the continuing downturn in the residential property market and related depressed consumer demand.

On this point, the best thing that can be said is that consumer demand has stabilised without any evidence as yet of a real upturn.

This is in the context of weak job growth and relatively weak income growth. Precise data points in this area are lacking.

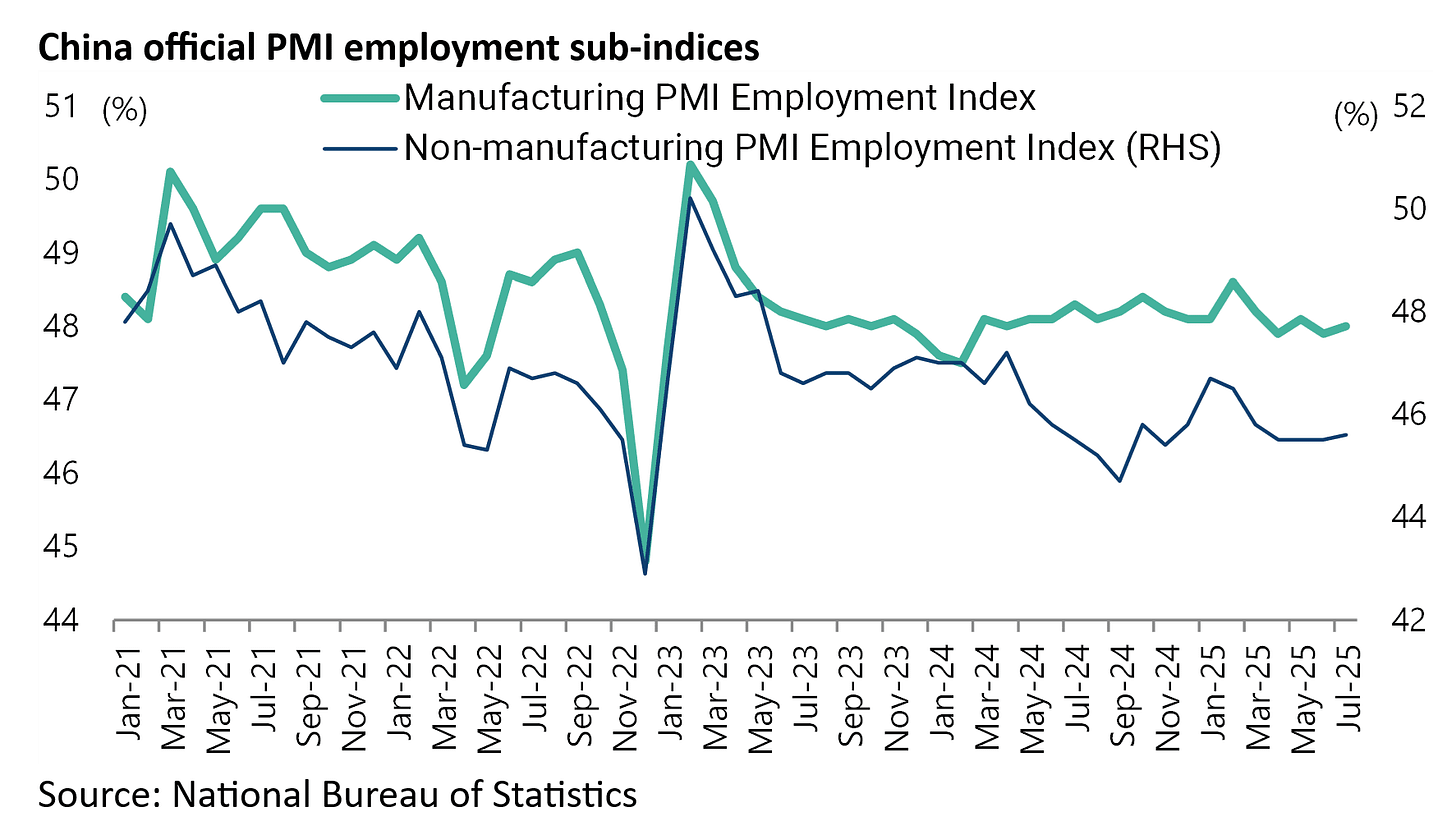

But the pattern is for the employment component of the PMI to lead income growth by about six-nine months. And the employment component has of late started to weaken again.

Thus, the National Bureau of Statistics’ Manufacturing PMI employment index has declined from 48.6% in February to 48.0% in July, while the Non-manufacturing PMI employment index is down from 46.7% in January to 45.6% in July.

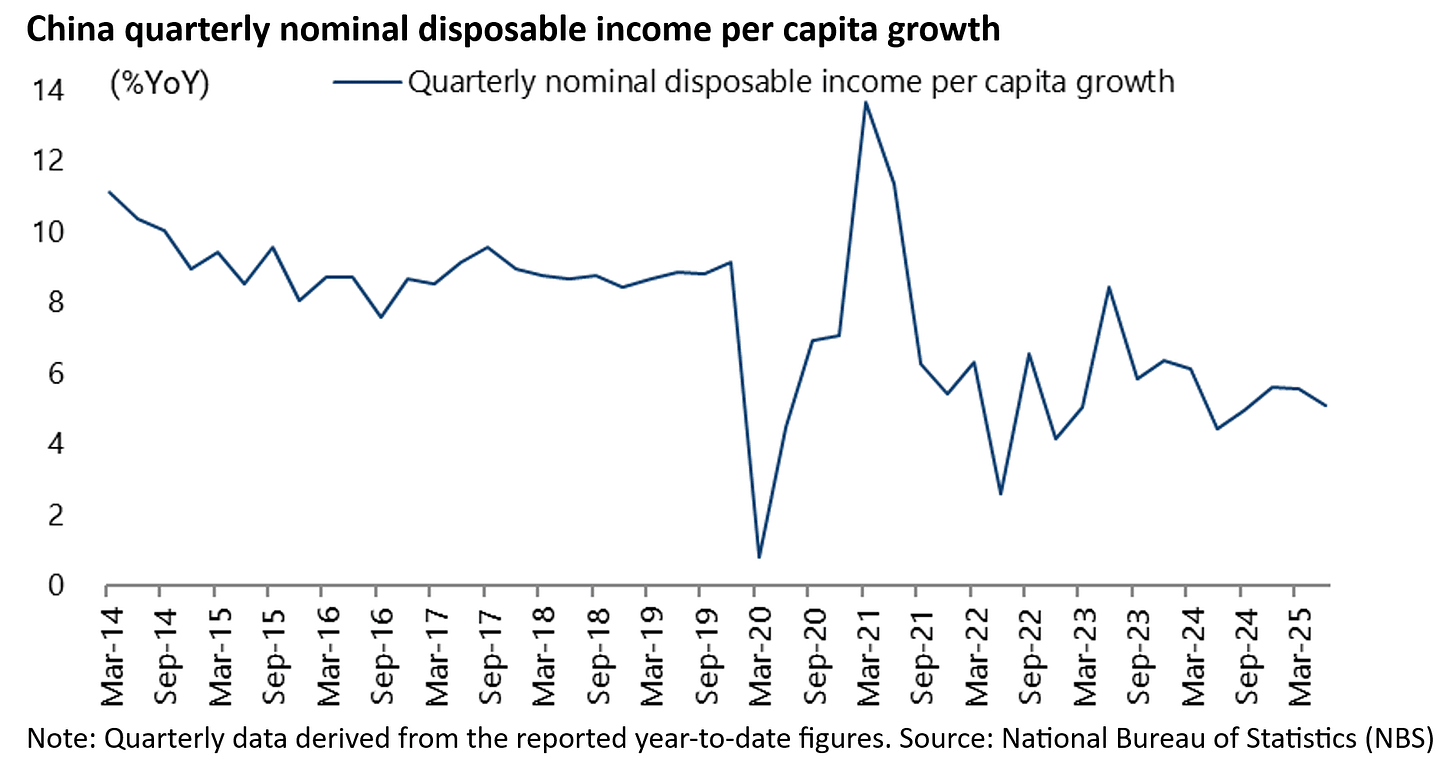

As for income growth, quarterly nominal disposable income per capita growth has risen from an estimated 4.5% YoY in 2Q24 to 5.6% YoY in 4Q24 and 5.1% YoY in 2Q25, after declining from 8.4% YoY in 2Q23.

This compares with the average annual growth of 9% in the six years prior to the pandemic.

Stimulus to Boost Consumer Spending is Far Too Little so Far

As regards consumption, the April Politburo meeting chaired by President Xi resulted in an explicit reference to the need for policies targeting service sector consumption.

The PBOC subsequently announced in May the establishment of a re-lending facility to increase low-cost funding for key service consumption sectors, such as hotels, restaurants, cultural and sports entertainment, education and elderly care.

The facility has a quota of Rmb500bn and an annual interest rate of 1.5% and a term of one year, while eligible applicants for the facility include 21 national financial institutions, such as policy banks and state-owned banks, as well as five systemically important city commercial banks.

Still the macro impact is tiny.

To put the Rmb500bn quota into context, the expenditure-based GDP data showed that household consumption totaled Rmb54tn in 2024, the latest data available.

So there has been a lack of real follow through in terms of policies specifically targeting services.

One view is that the central government is holding them in reserve should the Trump administration’s tariff agenda require a more effective policy response.

The obvious policy would be to hand out vouchers for service sector consumption, just as vouchers were used for the replacement of consumer goods.

China launched a national consumer goods trade-in programme in March 2024 which offered consumers vouchers or discounts of 15-20% when trading in old products for new ones, including eight categories of home appliances and vehicles.

The authorities expanded the programme in January to include electronic products and four more categories of home appliances as well as subsidies for the purchases of digital products such as mobile phones and tablets.

The Ministry of Commerce has stated that the consumer goods trade-in programme has generated Rmb1.1tn in sales in the first five months of this year.

The central government has earmarked Rmb300bn from ultra-long-term special treasury bonds to support this year’s trade-in programme, doubling the Rmb150bn in 2024.

Still again the impact is extremely limited in a macro context. Retail sales of consumer goods, excluding catering, totaled Rmb43tn in 2024 and Rmb22tn in the first six months of this year.

Could AI Applications Boost Services Spending?

The other problem with consumer-durable focused policies is clearly that they are one-off.

Whereas spending on services is a different story.

In this respect, the obvious way for China to boost the role of consumption in the economy is to increase spending on services, and here cheap AI applications would provide one source of hope.

It is also worth noting that China’s key retail sales data, which most investors look at as the best gauge of consumption, measures mainly the consumption of goods, while measures of consumption of services are relatively limited.

On this point nominal retail sales of consumer goods rose by 5.0% YoY in the first half of 2025, compared with 3.5% growth in the whole of 2024 and 7.2% in 2023 on the rebound after Covid-related lockdowns.

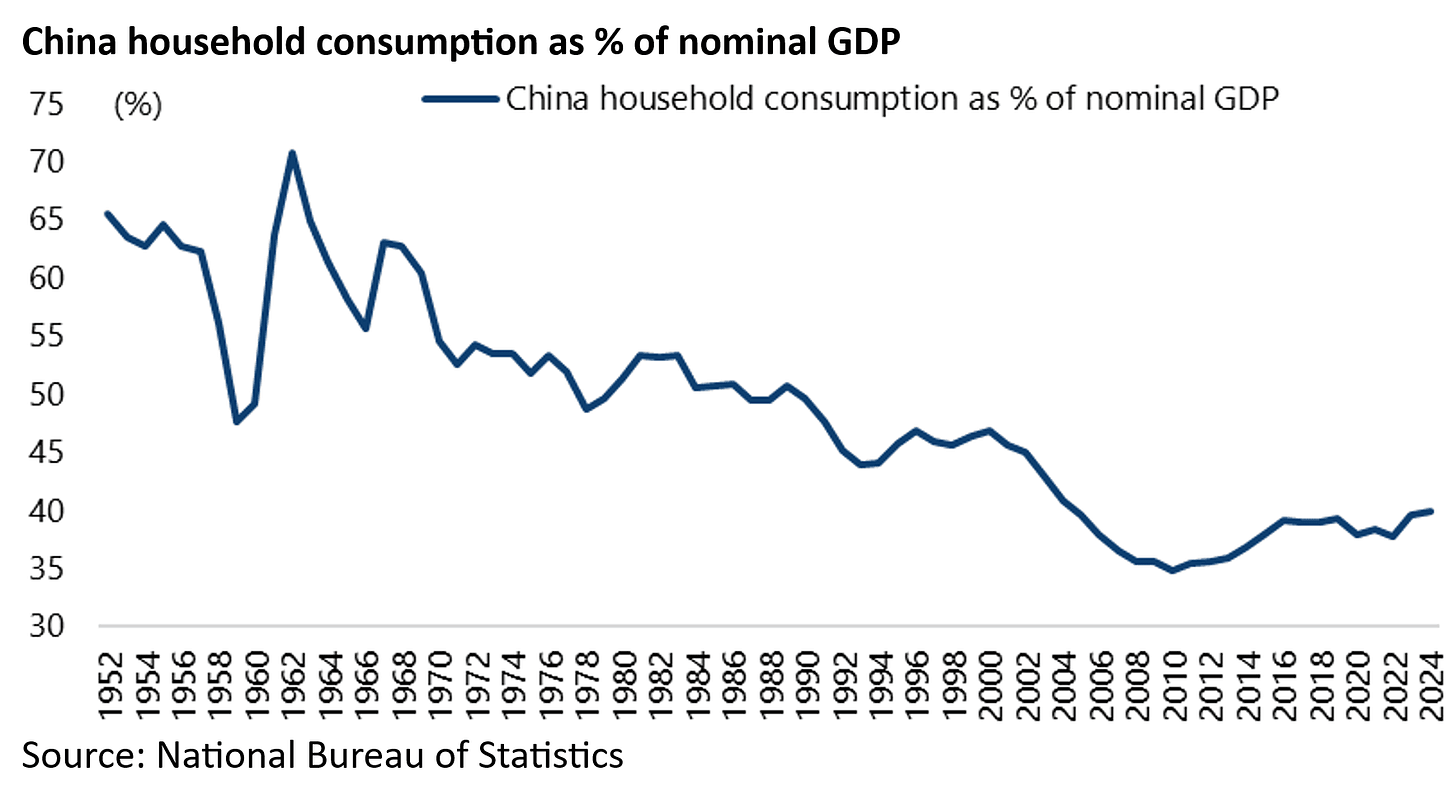

With China’s private consumption running at only 40% of nominal GDP, compared with 68% in America and 54% in Japan, there is clearly room for a lot of improvement.

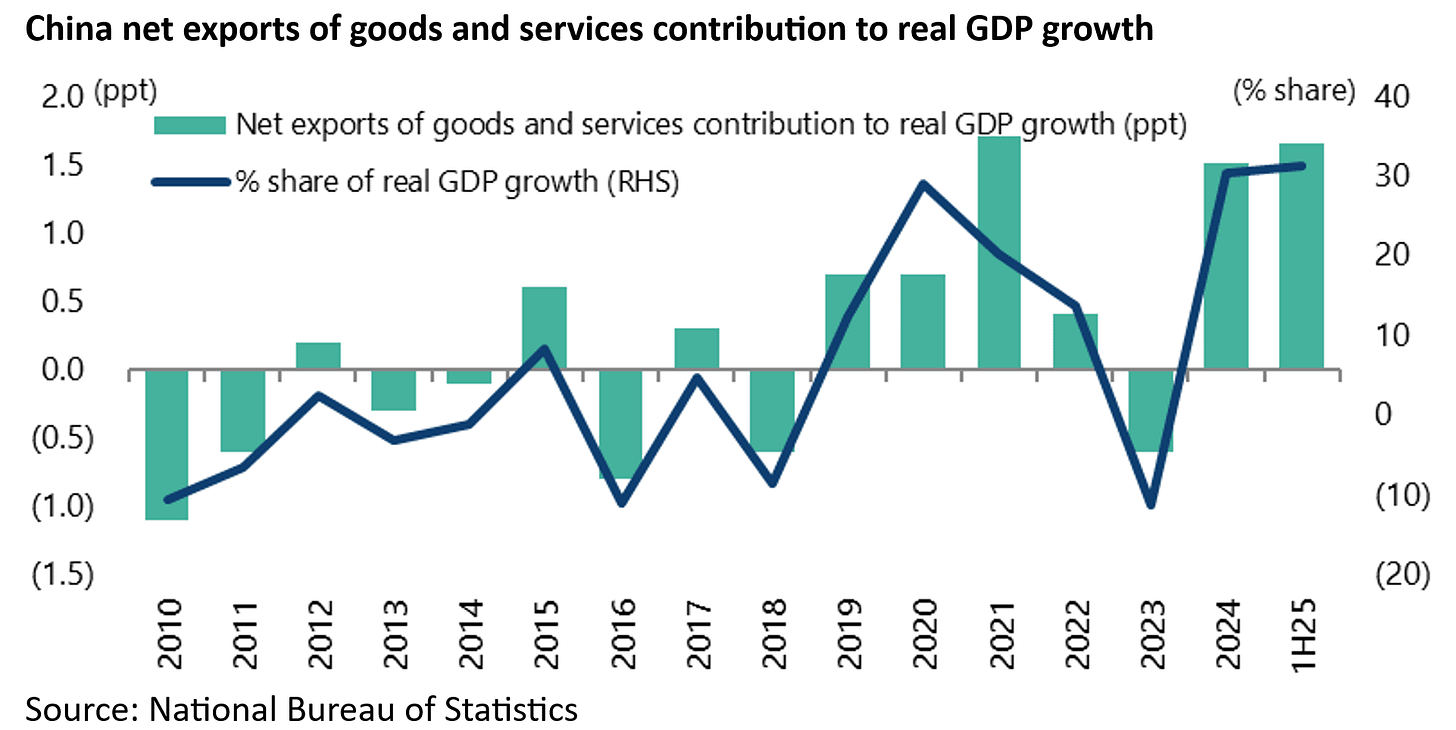

But for now, net exports have become again the main driver of real GDP growth in the post-Covid era whereas they had been declining in the pre-pandemic era.

Thus, net exports contributed 1.65 percentage points to China real GDP growth of 5.3% YoY in 1H25 and 1.5ppts to 5.0% growth in 2024, accounting for 31.2% of the 1H25 growth and 30.3% in 2024.

By contrast, net exports contributed a negative 0.6 percentage point to real GDP growth of 6.8% in 2018.

Export Data Remains Very Strong, Even with Tariff Pre-Buying by the World

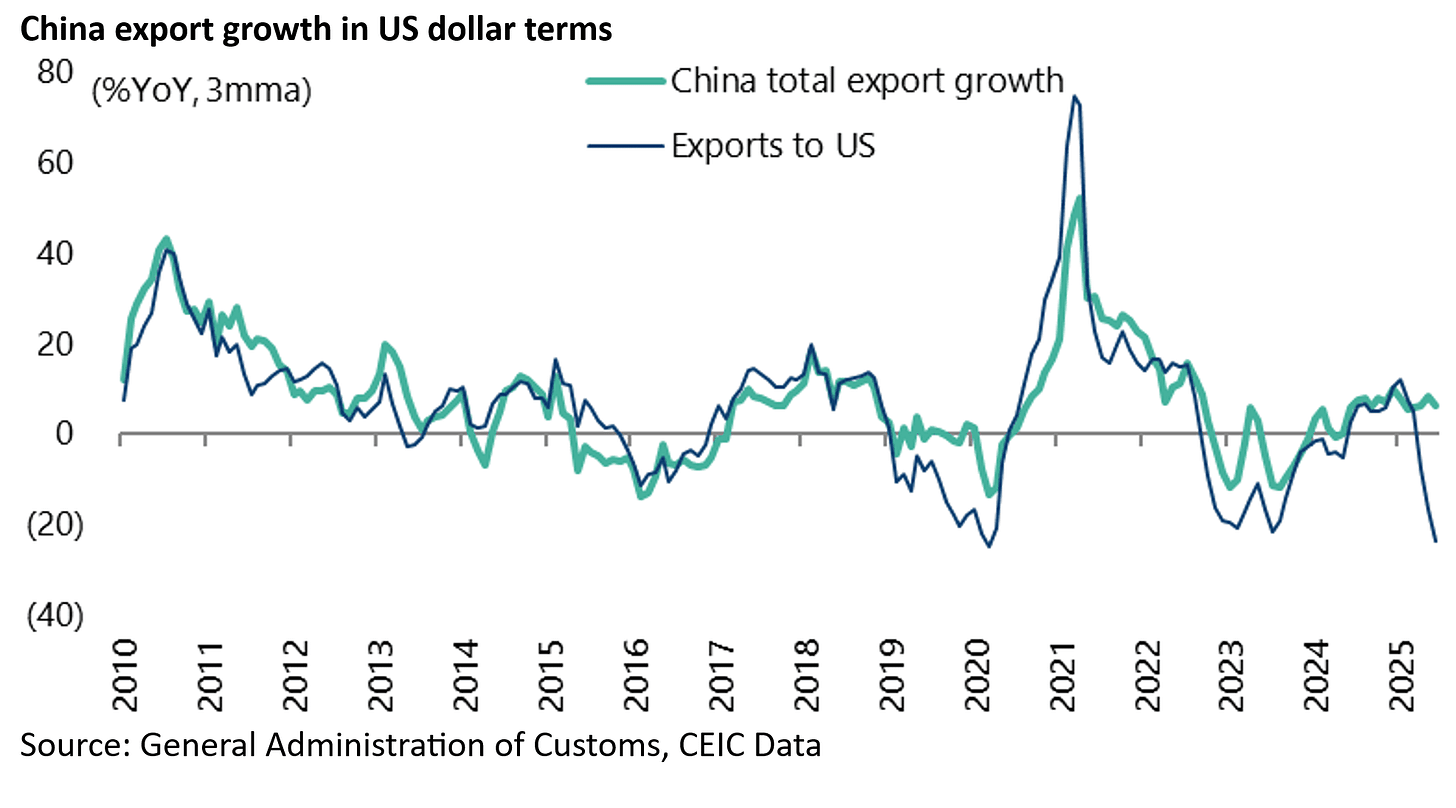

Export data remains remarkably strong even allowing for the front loading of demand created by the Trump administration’s threatened tariff strategy.

Total exports rose by 5.8% YoY in US dollar terms in June and are up 5.9% YoY in the first six months of 2025, even as exports to the US plunged by 34.5% YoY in May, the biggest drop since February 2020, and were down 16.1% YoY in June.

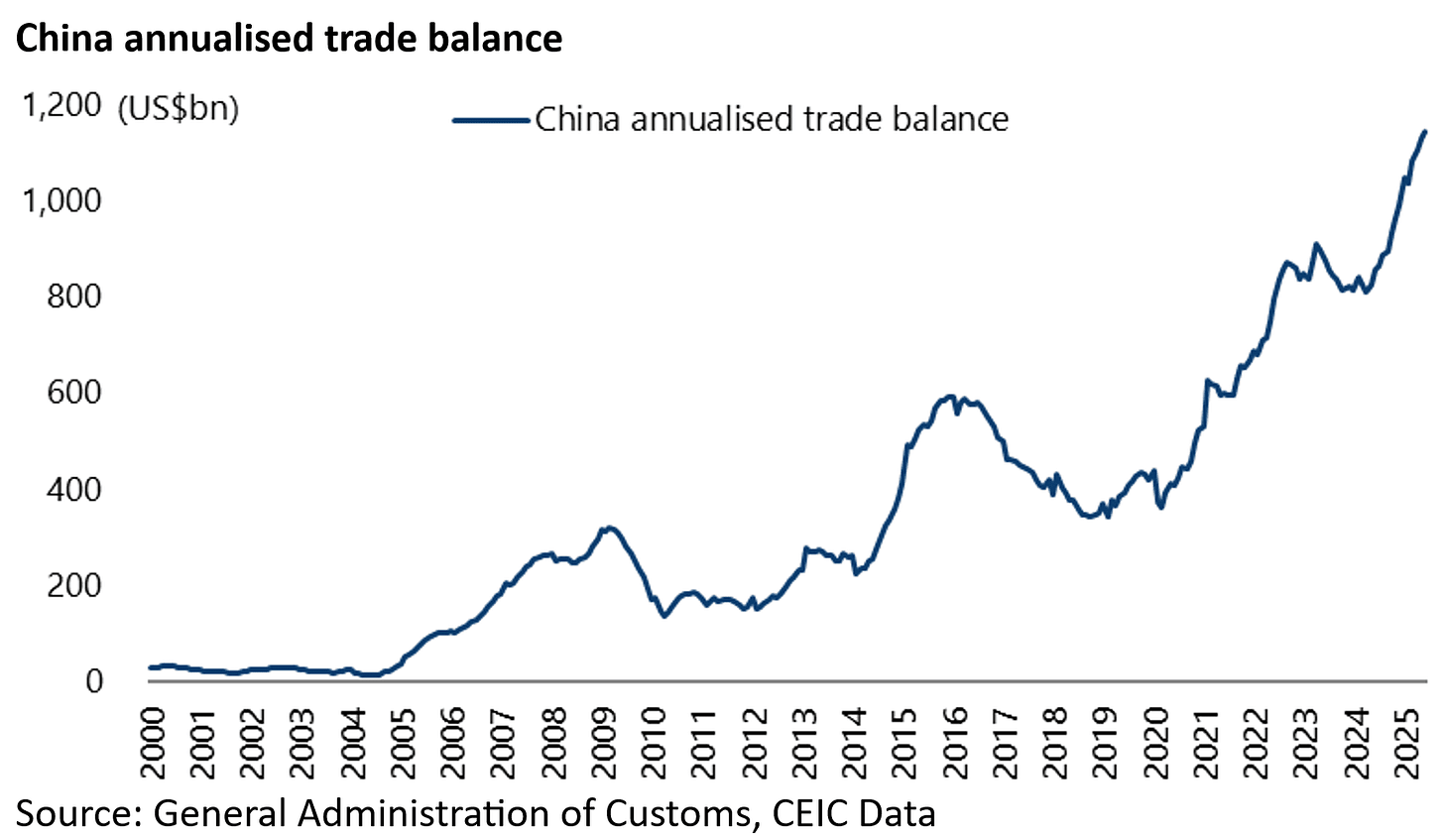

Meanwhile, China’s annualised trade surplus of goods rose by 33.4% YoY to a record US$1.14tn in the 12 months to June.

China’s continuing record trade surplus is one reason why the renminbi remains much more likely to appreciate against the US dollar than depreciate, just as the yen strengthened throughout most of Japan’s deflation era prior to the launch of yield curve control in September 2016.

Thus, the yen appreciated by 113% from Y160/US$ in April 1990 to Y75.4/US$ in October 2011 and was still Y99/US$ in June 2016.

Deflation Remains Entrenched in China

For now deflation remains entrenched in China with PPI negative for 33 consecutive months, though CPI rose to 0.1% YoY in June after remaining negative in the previous four months.

PPI deflation has deteriorated from 2.2% YoY in February to 3.6% YoY in June, the worst in 23 months.

PPI is likely to remain negative unless there is another wave of supply-side reform to reduce excess capacity as happened in 2016.

There is growing talk about this but it is so far based more on production cuts.

There are also growing official concerns about price cuts and excessive competition as reflected in the decision by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) last quarter to call in BYD and other EV makers recently to caution against excessive price cutting.

This occurred after BYD announced that it was reducing prices on 22 EV models by up to 34% (see Bloomberg article: “China warns BYD, Rivals to Self-Regulate on Price War Woes”, 5 June 2025).

There was also a similar official warning concerning the food delivery space given JD.com’s recent decision to enter this business dominated by Meituan and launch a cash-burning strategy to gain market share.

If this suggests the central government understands that there can be too much of a good thing in terms of price competition, it is also the case that Japanese-style liquidity preference associated with deflation seems well entrenched among savers.

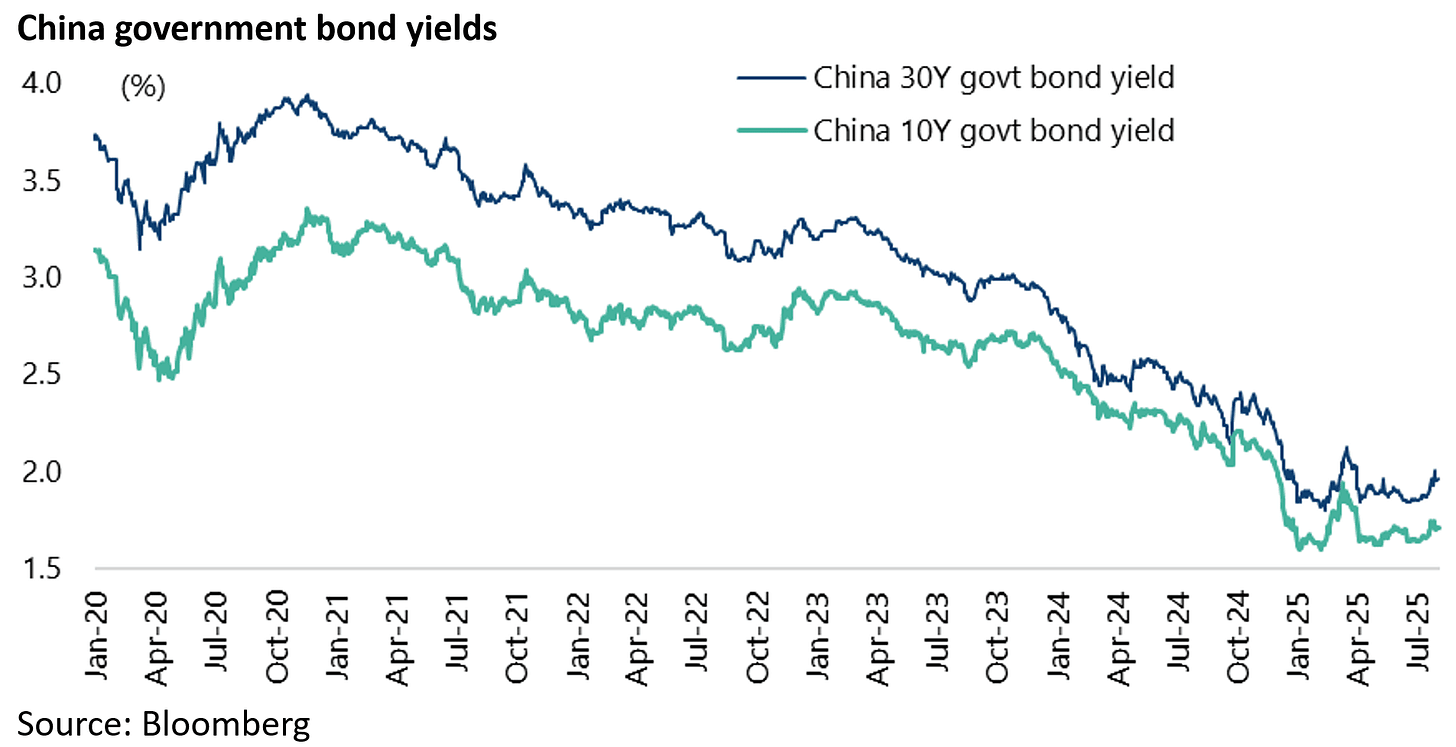

With short-term bank deposits now yielding only 0.95%, a 10-year government bond yield at 1.71%, though up from an all-time-low of 1.59% in January, and a 30-year yield at 1.96% look relatively attractive.

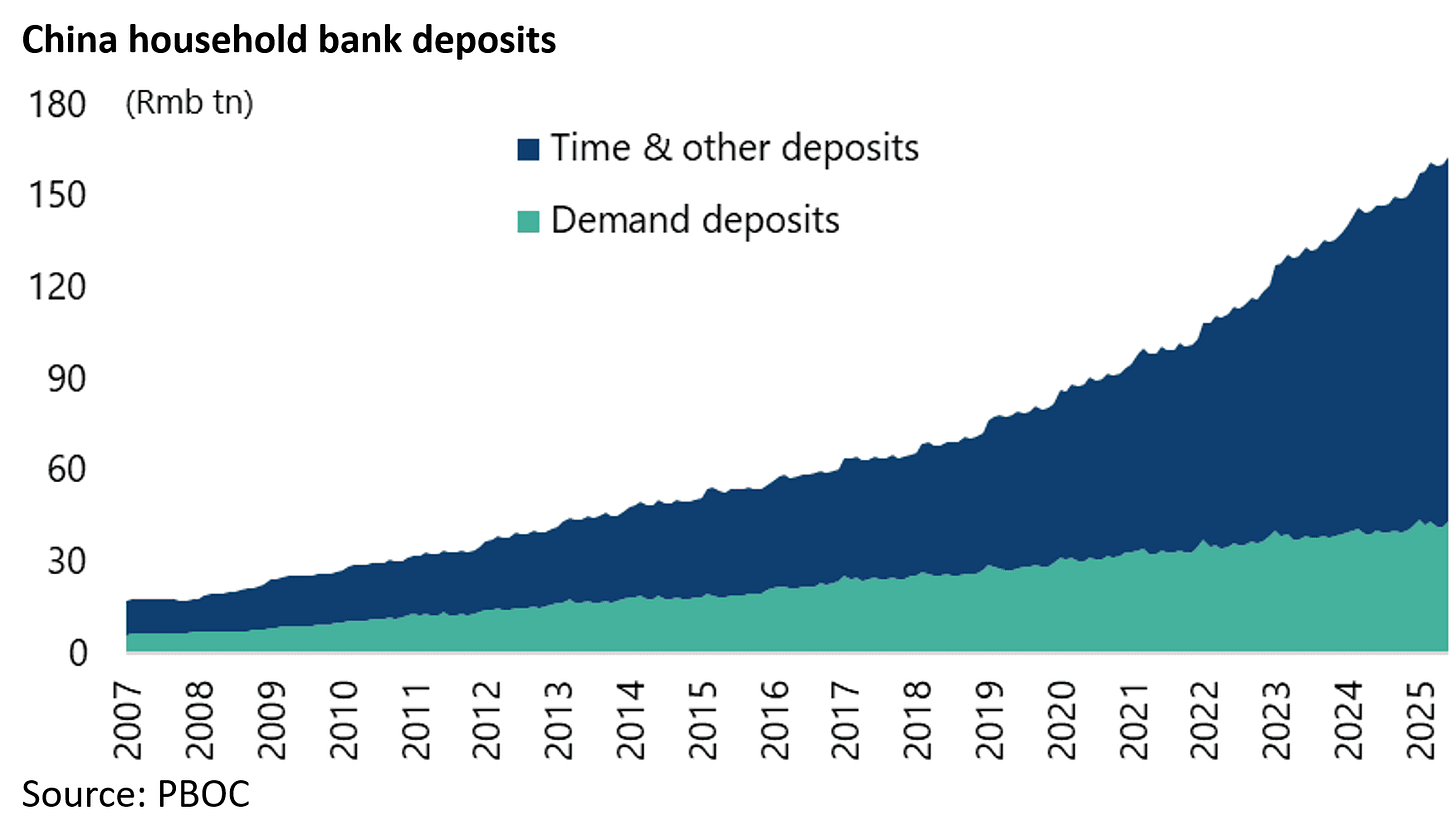

On this point, it should be noted that about Rmb120tn of the Rmb163tn in household bank deposits is locked up in time deposits.

Pent Up Housing Demand Has Been Exhausted in Mainland China

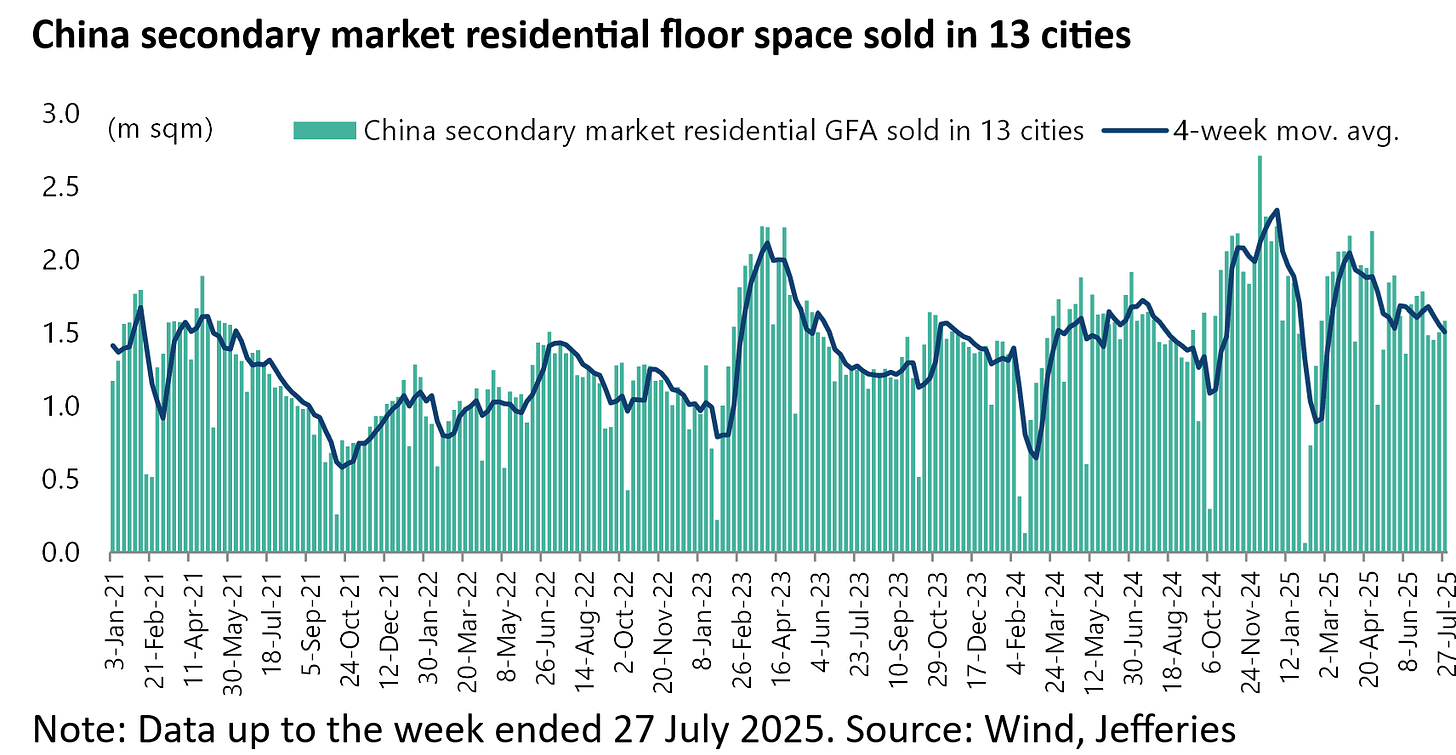

As for the residential property market, secondary market transactions in the top 13 cities have picked up in the last nine months though they have now turned down again as pent up demand is absorbed.

Thus, weekly secondary market residential property sales in 13 major cities rose by 15% YoY to an average of 1.61m sqm in the first 30 weeks of 2025 ended 27 July, though they have since declined by 6.6% YoY to 1.5m sqm in the four weeks to 27 July.

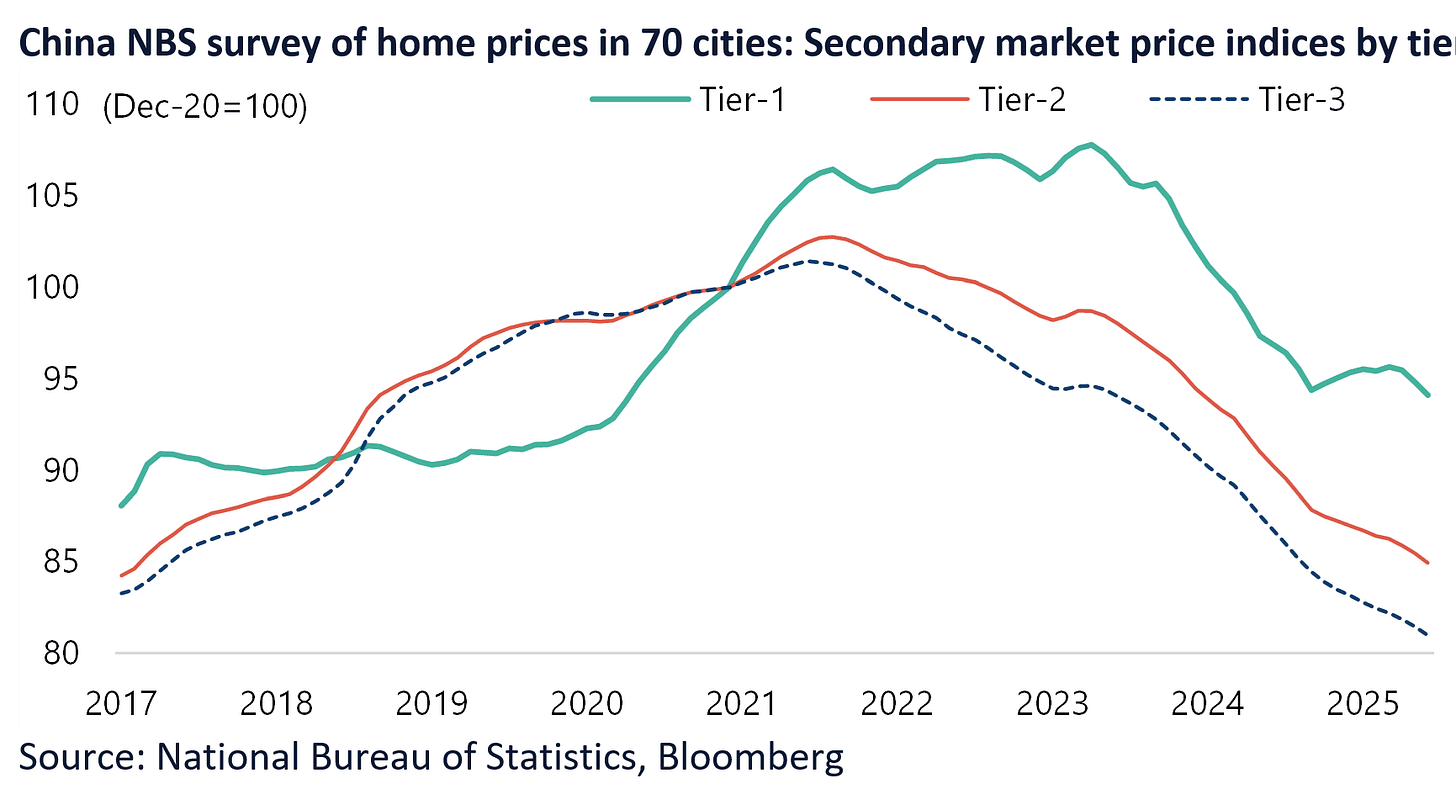

As for residential prices in the major cities, the official price data does not reflect the extent of the decline.

The National Bureau of Statistics’ home price survey data shows that secondary market residential prices in Tier-1 cities have declined by an average 13% from the peak in 2023, with prices in Guangzhou and Shenzhen down 20% and 16% respectively from their 2021 peak.

While secondary prices in Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities are down 17% and 20% from their peak in 2021.

In reality prices are probably down by up to 30% from the peak in the major cities if there is a forced seller whereas in Tier 3 and 4 cities they could already have halved.

Still the saving grace in China remains the absence of any mortgage debt crisis and the resulting deflationary dynamic of negative equity triggered distress selling.

This reflects the high downpayments with maximum loan-to-value ratios of only 50% at the peak of the property boom.

Parents have also continued to support the next generation in terms of contributing towards downpayments.

The result is that President Xi has undoubtedly succeeded in weaning the Chinese economy off its previous dependence on property and moving the strategic focus towards a technological upgrading which makes eminent sense given the demographics.

DeepSeek is only one of several signs that this is starting to pay off.

Wages are Being Cut in Finance to Push New Students Towards Tech-Related Fields

The focus on tech and the end of the property era is also reflected in the trend in higher education.

For just as the central government has squeezed property so it has deliberately implemented wage cuts in the financial services sector to encourage China’s top students to pursue careers in tech-related areas.

As a result, the top undergraduates all now want to study science courses.

By contrast, with salaries in the securities and fund management industries down by as much as 30-40%, degrees in finance and MBAs are completely out of fashion.

The result is a central government-driven re-allocation of China’s best human resources.

Still if the financial sector is completely out of favour, the central government is still supporting the stock market as a policy tool as remains clear in the continuing pressure on quoted companies to raise dividend payouts and increase share buybacks.

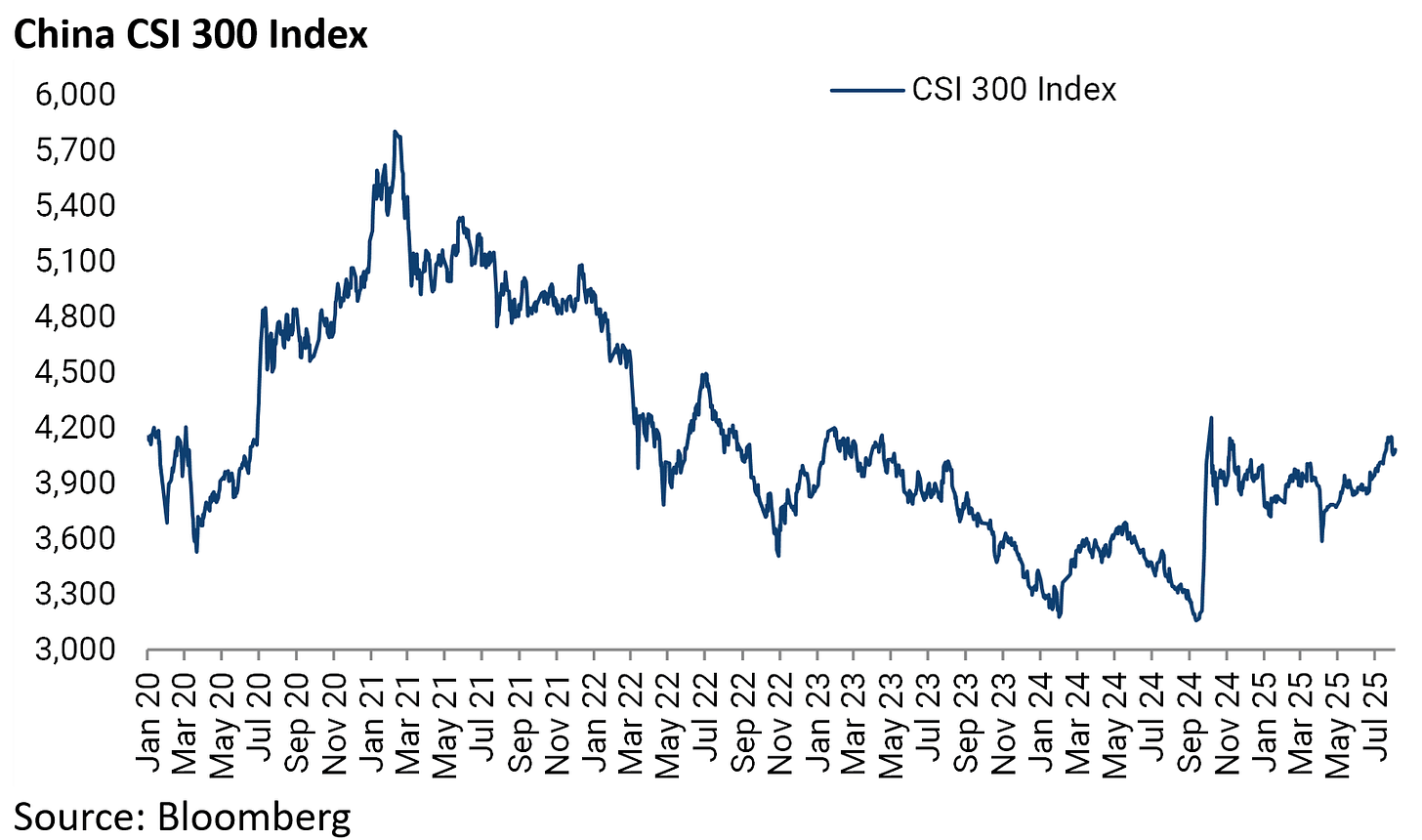

This is one reason why this writer continues to believe the Chinese stock market, defined as the CSI 300 Index, made a major bottom last September despite the continuing deflationary backdrop and L-shaped “recovery” as regards domestic demand.