Is Trump's Focus on Low Yields and Low Volatility Good for Your Wallet?

Author: Chris Wood

There is no doubt that the Trump administration remains focused on getting the cost of debt servicing down.

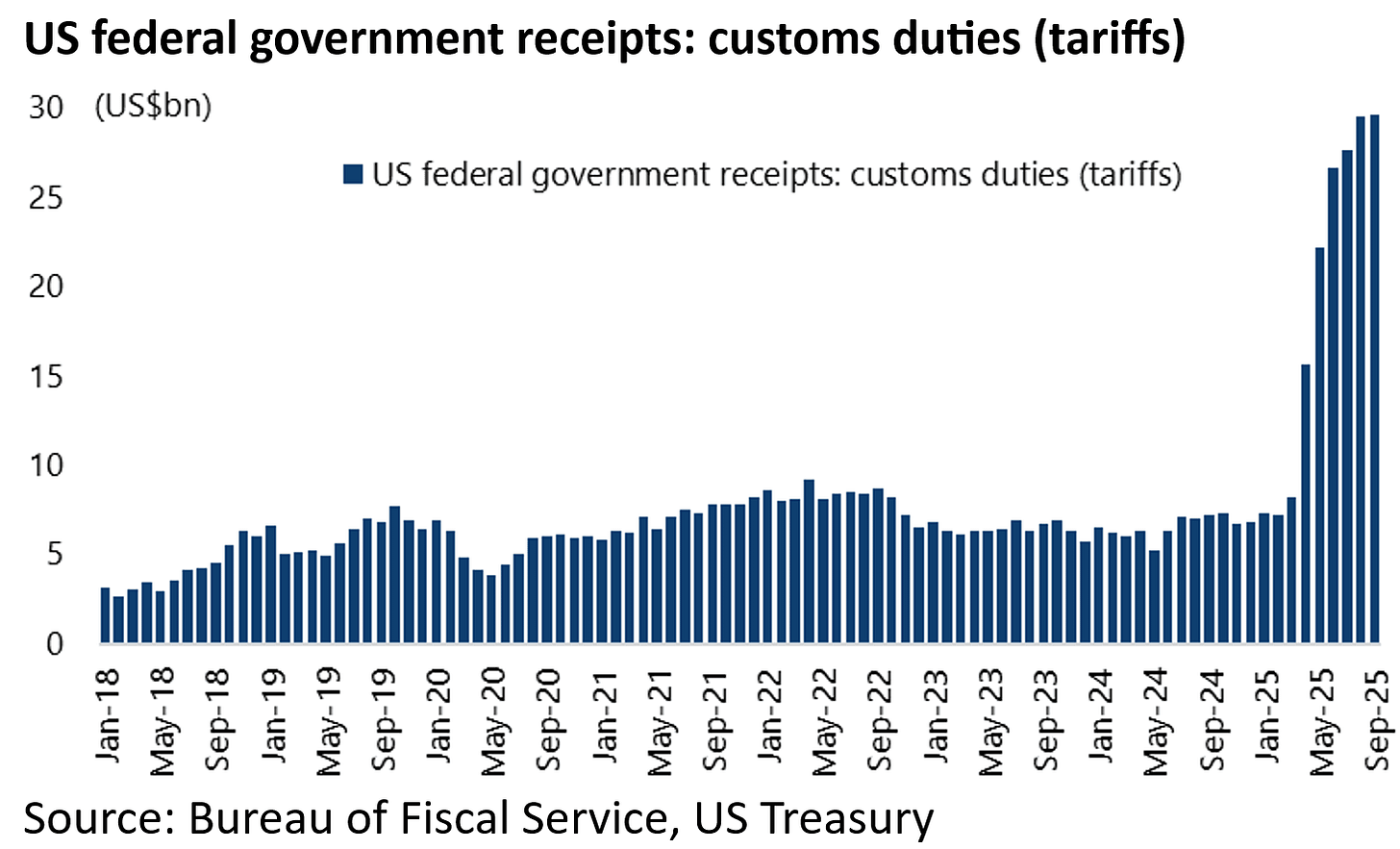

The strategy seems to be to try to grow out of America’s fiscal debt problem, with a little help of course from surging tariff revenues currently running at US$29.7bn in September or an annualised US$356bn.

This explains in large part the continuing pressure on the Fed to cut rates, which Fed chairman Jerome Powell has partly reciprocated with 50bp of rate cuts since mid-September even though inflation remains above the Fed’s 2% target. CPI was 3.0% YoY in September.

Scott Bessent has called for the Fed to do more, having stated in August that the neutral rate is about 1.5 percentage points lower than the then federal funds rate level of 4.25-4.5% (see Bloomberg articles: “Bessent Urges Fed to Lower Rates by 150 Basis Points or More”, 13 August 2025 and “Bessent Says He’s Not Pushing Fed Cuts, Just Touting Models”, 14 August 2025). It is now 3.75-4.0%.

Similarly, Bessent is also seemingly focused on keeping the US Treasury bond market as calm as it has undoubtedly been of late.

US Bond Yields Remain Subdued, Unlike in Japan and Elsewhere

This probably explains his public criticism of the Bank of Japan for not hiking rates following its meeting at the end of July.

Bessent told Bloomberg at the time that the BoJ is “behind the curve” and that “they are going to be hiking and they need to get their inflation problem under control” (see Bloomberg article: “Bessent Says BOJ Is Falling Behind the Curve, Expects Hike”, 14 August 2025).

The Japanese central bank opted to stay on hold with Governor Kazuo Ueda sending the doveish message at the post-meeting press conference that the desired approach was to wait and see the impact of tariffs on both the Japanese and American economies in the second half of this year.

Moreover, the Japanese central bank stayed on hold at its meeting last week.

It is highly unusual for a US Treasury Secretary to comment on a Japanese central bank meeting in this fashion.

In fact, this writer cannot remember such a precedent.

Still the motive seems to be to avoid negative bond market volatility.

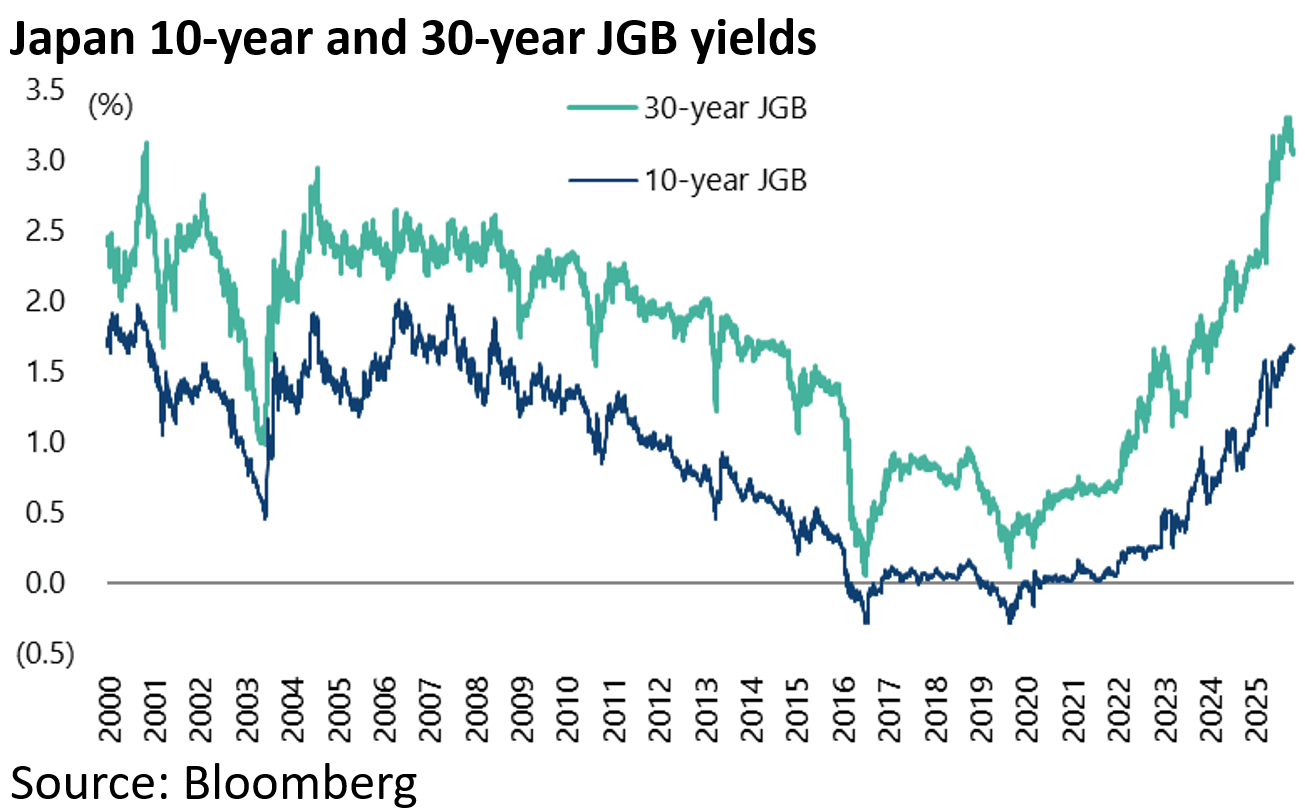

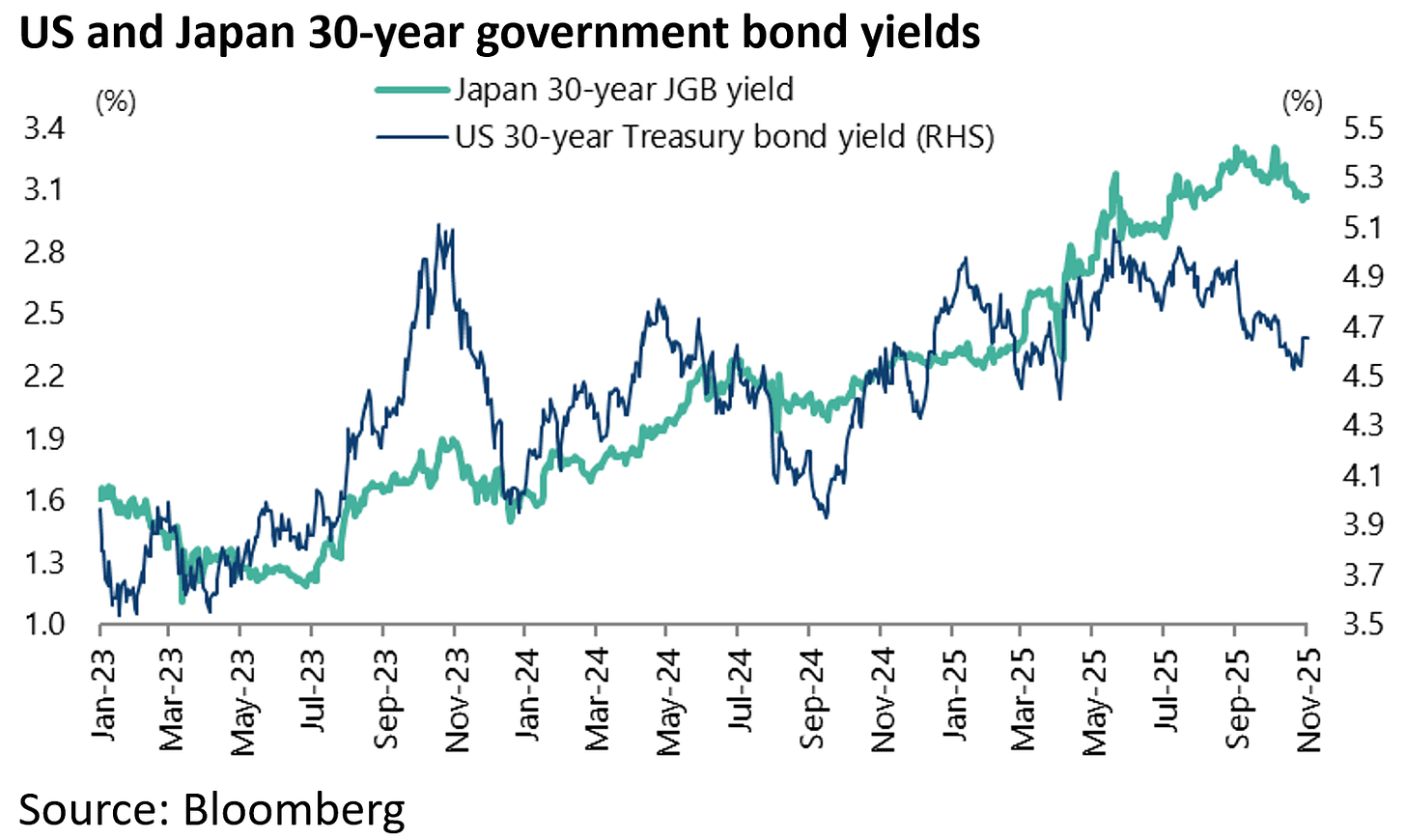

The Japanese 10-year and 30-year bond yields remain at near multi-year highs.

The 10-year JGB yield rose to 1.71% on 10 October, the highest level since July 2008, and is now 1.67%. While the 30-year JGB yield rose to a record 3.35% on 7 October and is now 3.06%.

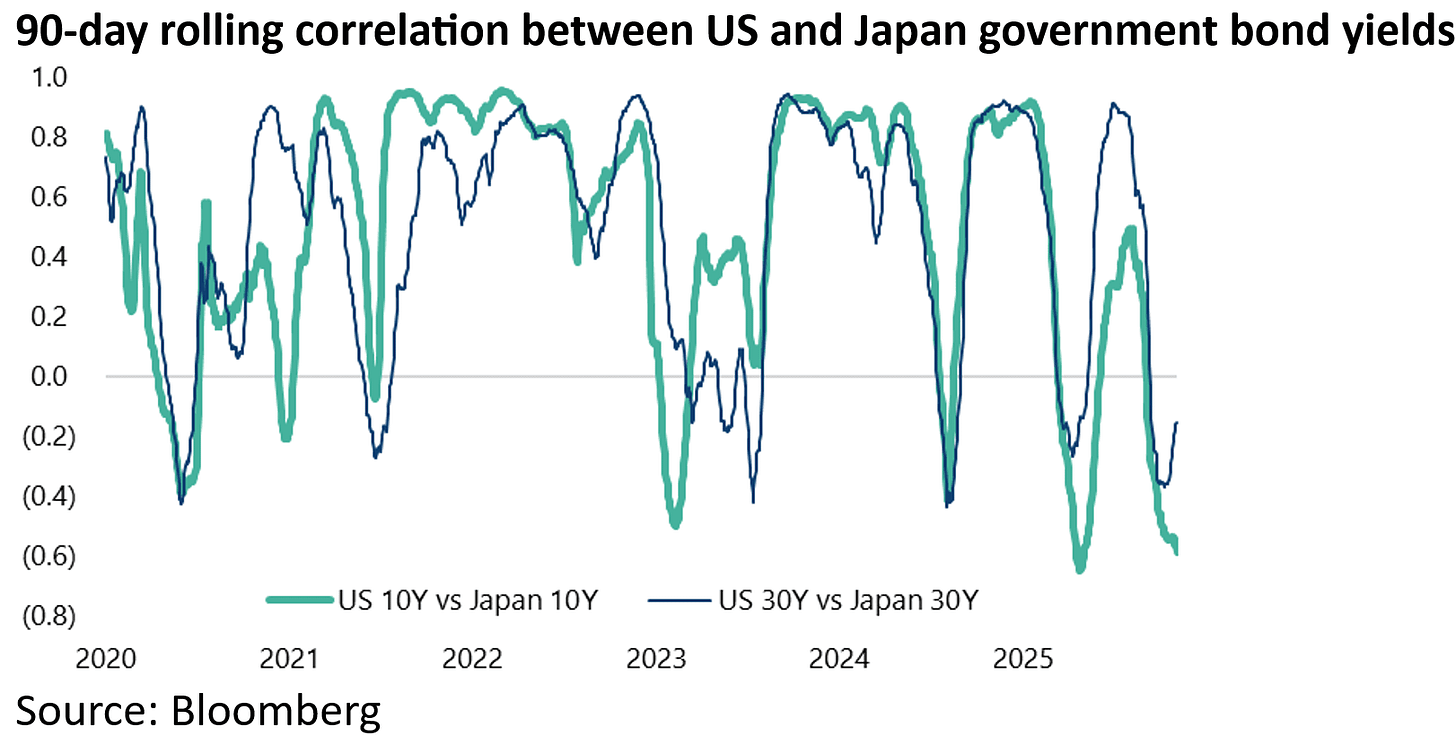

Still their correlation with the long end of the US treasury bond market has continued to decline, a feature of the past nine months.

Indeed the rolling 90-day correlation between US and Japan 30-year government bond yields has collapsed from 0.87 in mid-January to a negative 0.16 at the end of October.

While the correlation between US and Japan 10-year yields is down from 0.92 to a negative 0.58 over the same period.

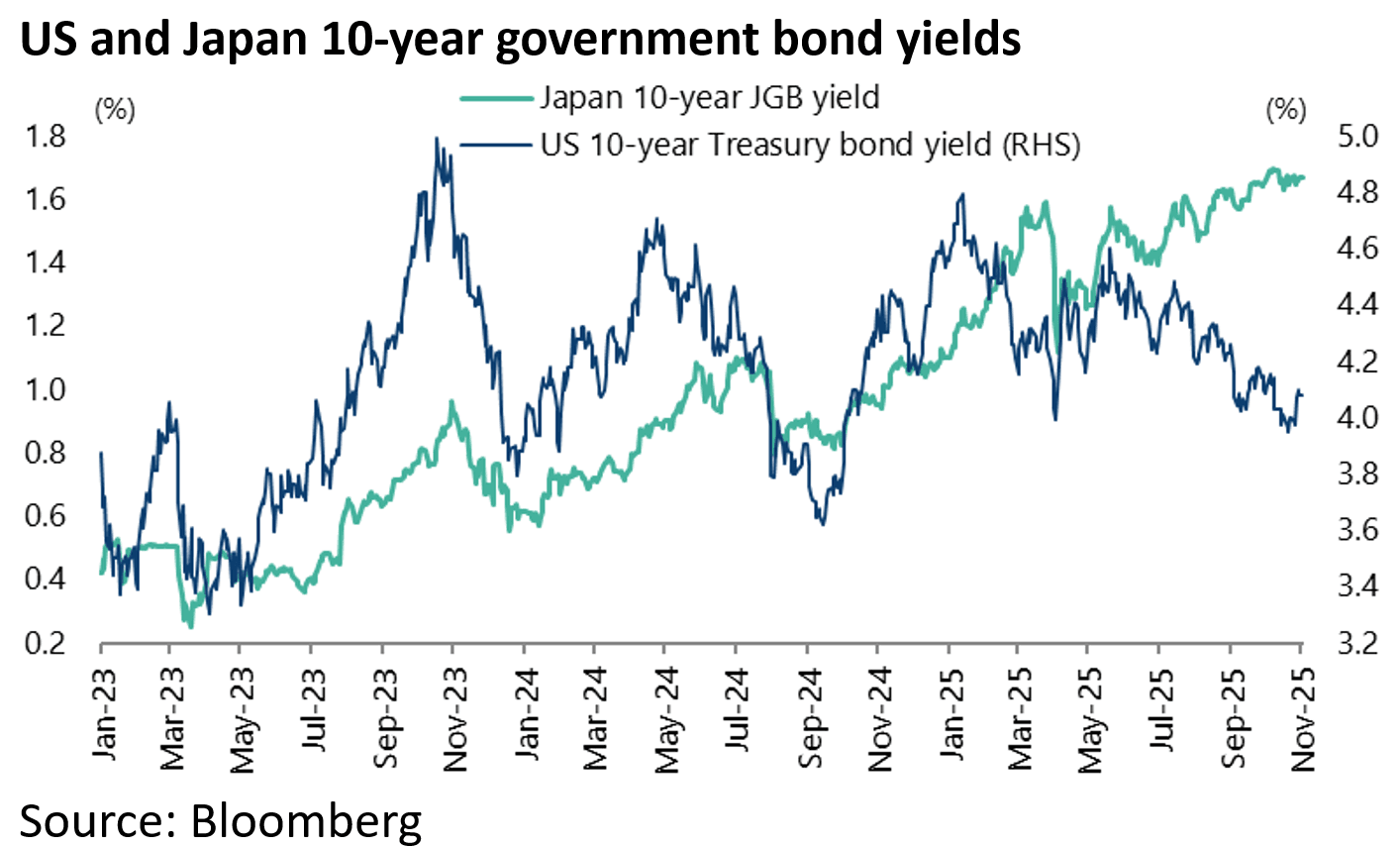

This is a positive from a US standpoint in the sense that the long end of the Treasury market has not sold off in conjunction with JGBs.

The US 10-year and 30-year Treasury bond yields have declined by 73bp and 35bp from 4.81% and 5.0% in mid-January,

while the Japan 10-year and 30-year JGB yields are up 42bp and 73bp over the same period.

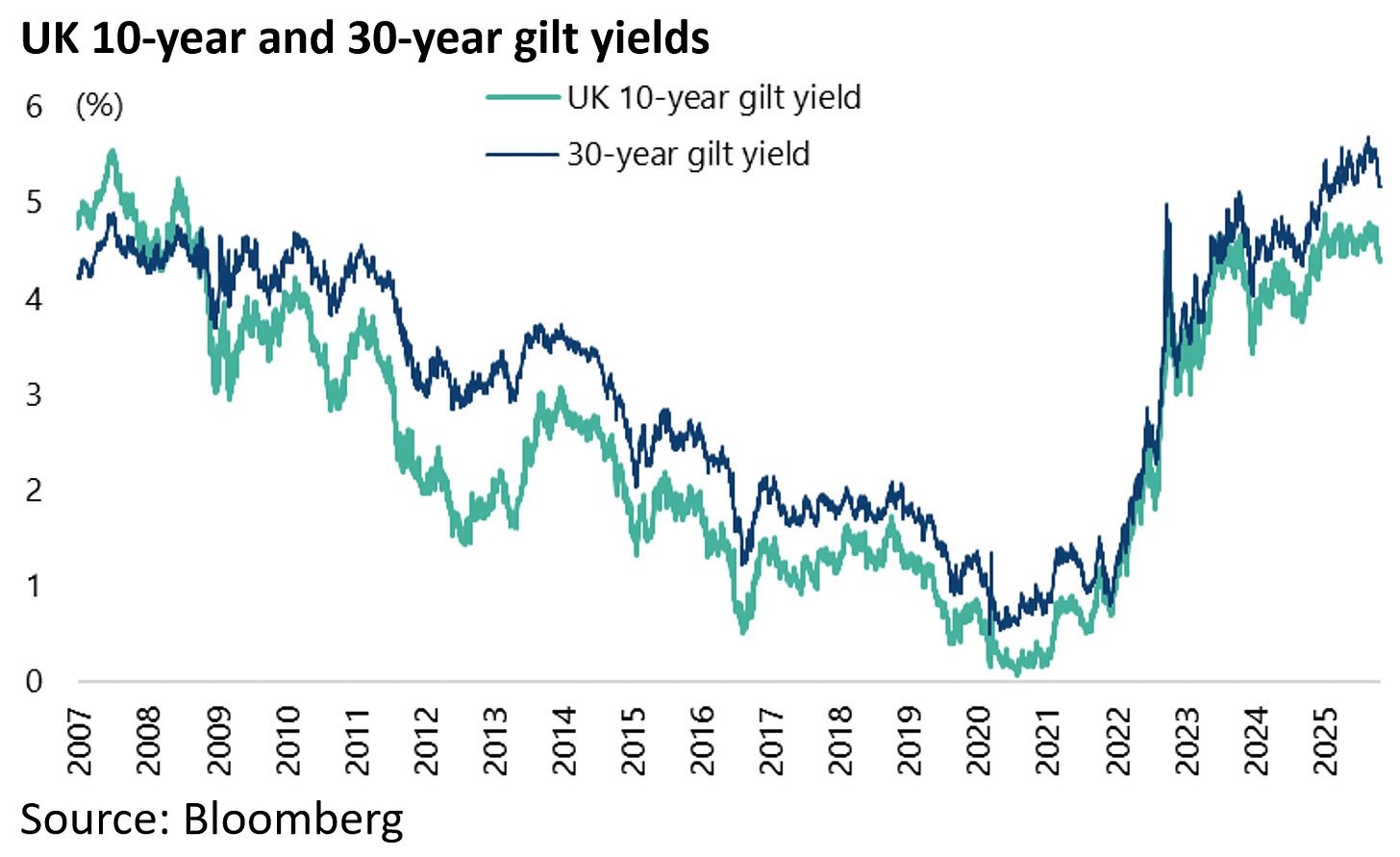

Nor for that matter has the US Treasury market been selling off with long-term British gilts where yields have also been near multi-year highs of late.

The 10-year and 30-year gilt yields rose to a recent high of 4.92% and 5.75% in January and September respectively, the highest levels since July 2008 and May 1998 respectively, though they have since declined to 4.41% and 5.18%.

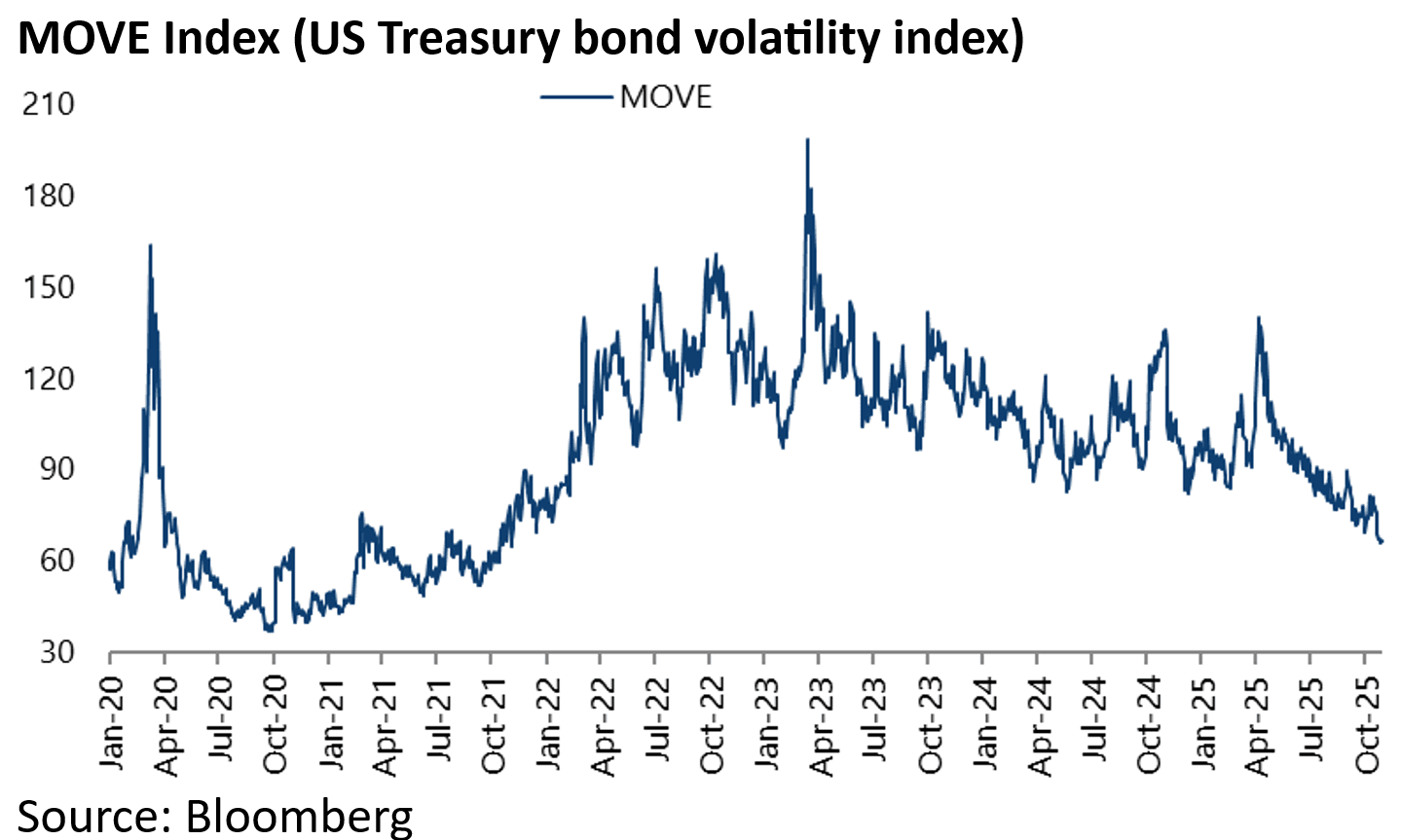

In this respect, the US Treasury secretary will undoubtedly have been pleased by the dramatic decline in bond volatility since the Treasury market sold off on the original Liberation Day tariff announcement on 2 April.

The so-called MOVE index, which measures implied Treasury bond market volatility by tracking a yield-curve weighted basket of options, has declined by 53% from a recent high of 139.88 on 8 April to 65.75 on 29 October, the lowest level since November 2021, and is now 66.61.

The Treasury is Targeting Low Volatility on Both the Short and Long End of the Curve

Meanwhile, it is clear that Bessent is highly focused on not only getting short-term rates down but also avoiding disruption at the long end of the market.

This can be seen not only in the ever-growing resort to short-term issuance previously discussed here (see An Exploration of Trump’s View on Crypto, Short Term Treasuries and Yield Curve Control, 11 September 2025), but also in the decision to buy back more long-term Treasuries.

The US Treasury announced in the quarterly refunding review in late July that it would double the frequency of liquidity support buybacks in both the 10-20 year and 20-30 year nominal coupon buckets from two times per quarter to four times per quarter.

This would increase the maximum aggregate size of liquidity support buybacks from US$30bn to US$38bn per quarter.

But whatever the tactics they seem to have been working in the sense that the recent calm in the long end of the Treasury bond market, reflected in the plunge in the MOVE index, has been a major contributing factor to the US equity rally of recent months helped of course by the positive tax consequences for corporates of OBBBA as well as investors’ renewed enthusiasm for celebrating surging AI capex.

None of this makes this writer want to alter the view that Treasury bonds are in a structural bear market.

Still it needs to be acknowledged that the Trump administration as a matter of policy seems clearly focused on keeping yields down, which is also another reason to assume that downward pressure will remain on the US dollar.

Fed Independence Clearly Weakened with Stephen Miran’s Appointment as a Fed Governor

On this point, it is further worth noting that Stephen Miran, author of the by now notorious paper advocating foreign creditors own discounted long-term treasury bonds in return for so-called “security guarantees” (see Hudson Bay Capital report: “A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System” by Stephen Miran, November 2024), was appointed Fed governor in mid-September in addition to his existing position as chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers.

Miran is on record as not being a fan of Fed independence, as will be self-evident to anyone who has read another of his papers (see Manhattan Institute article: “Reform the Federal Reserve’s Governance to Deliver Better Monetary Outcomes” by Dan Katz and Stephen Miran, 14 March 2024). Not that this writer has ever believed in Fed independence save for when Paul Volcker was running the place.

Are Stablecoin Flows a Zero Sum Game?

Then there is also the issue of the Trump administration’s promotion of stablecoins as a means to trigger demand for short-term Treasury securities, as also previously discussed here (see An Exploration of Trump’s View on Crypto, Short Term Treasuries and Yield Curve Control, 11 September 2025).

On this point, it is worth noting the pushback that has come from some economists.

This is that any increase in demand due to shifts into stablecoins could be “offset almost 1:1 by a shift out of bank deposits, money market funds and currency”, to quote one monetarist economist.

Or in other words the global demand for short-term Treasuries would not be changed, only the instruments by which people or firms hold the Treasuries.

On this point it is interesting to note that the minutes of the meeting of the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC) held in late April revealed that there was a debate on precisely this issue.

And the discussion continued in the latest meeting in late July as reflected in a TBAC letter to Bessent on 30 July.

To quote from the relevant section of the letter: “Increased stablecoin issuance could create a new source of demand for short-maturity Treasury securities.

While this might be offset by a reduction in demand from traditional Treasury investors if stablecoins act as a substitute for deposits, money market funds, or other cash-like instruments, much of the Committee seemed more optimistic about this as a source of new demand for T-bills. Potential impact to bank deposits bears close monitoring.”

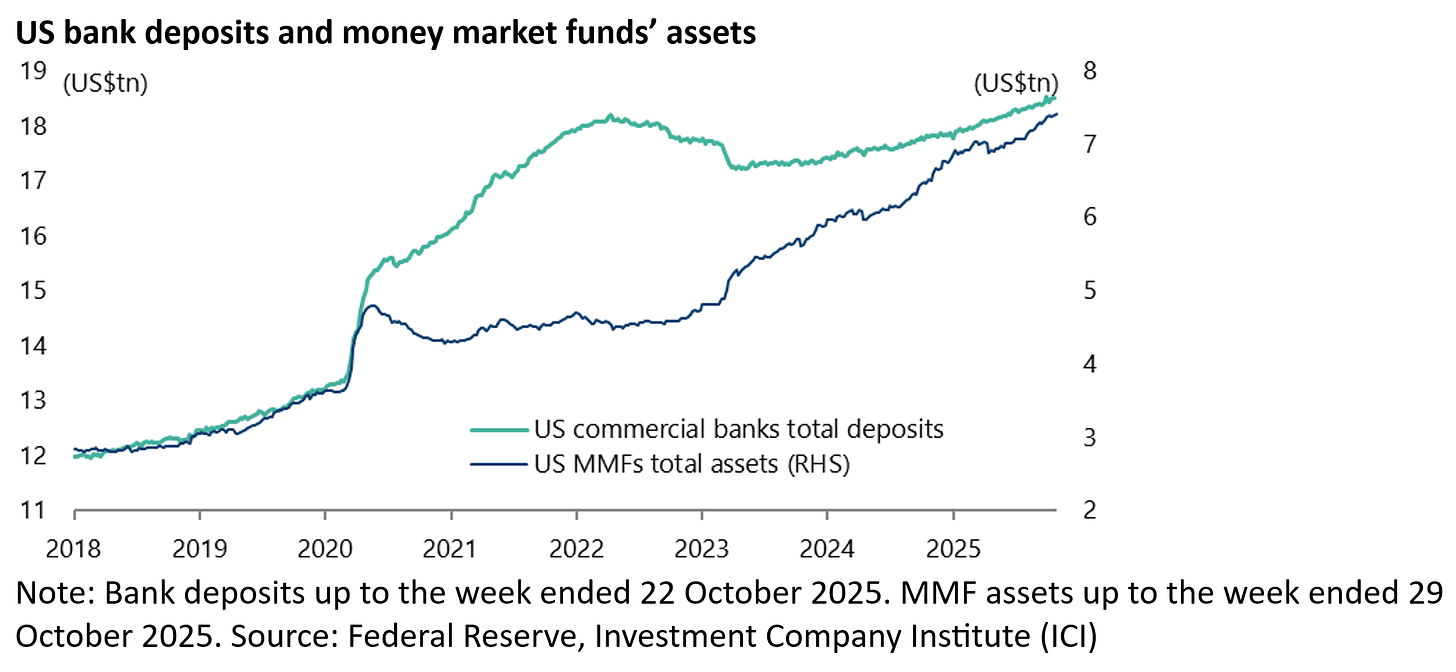

That point about monitoring bank deposits clearly makes sense given this issue could well become of macro importance if the forecast growth in stablecoins takes place.

Thus, one of the TBAC members in the April meeting projected that stablecoins could increase 8.3-fold by the end of 2028, rising from US$234bn to nearly US$2tn. There is currently more than US$120bn of Treasury securities backing stablecoins.

Meanwhile, by way of comparison, US bank deposits currently total US$18.5tn, while US money market funds total US$7.4tn.

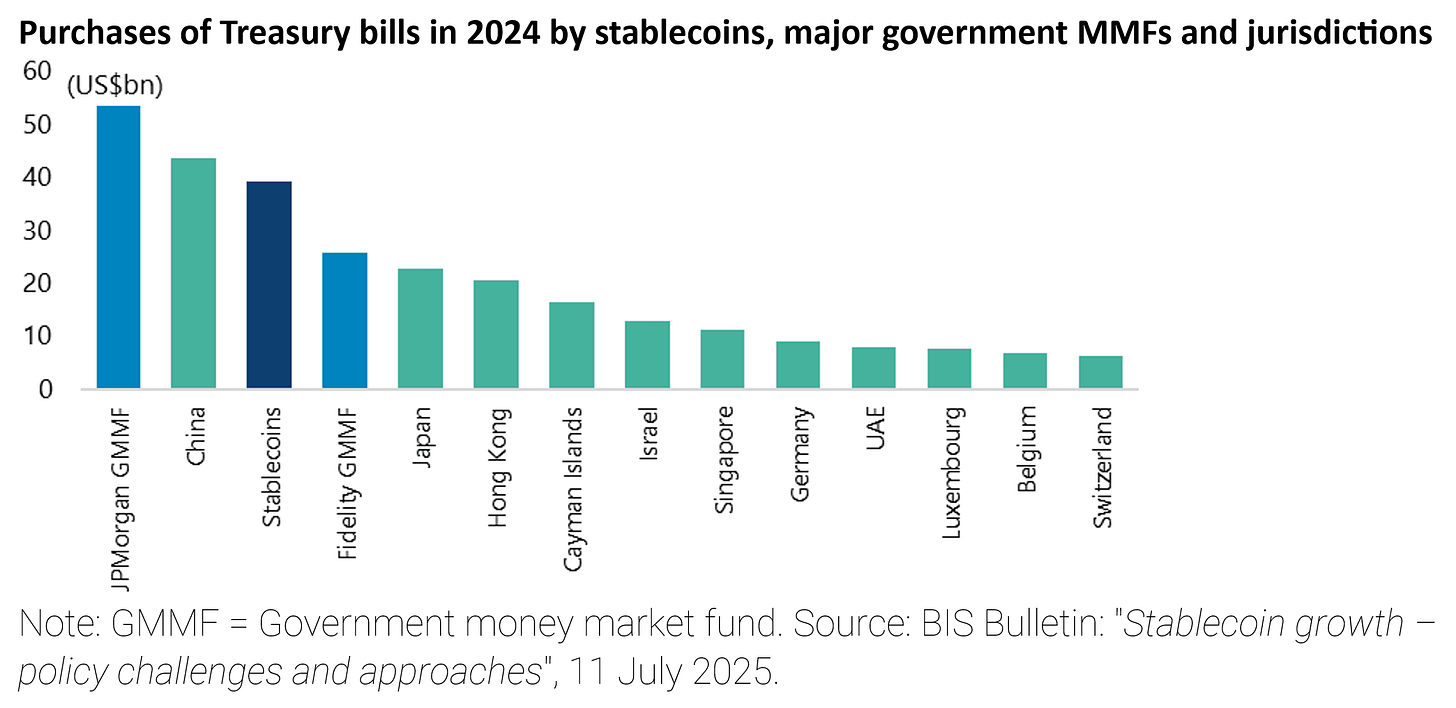

It is also worth recording that the BIS estimated in July that stablecoins bought nearly US$40bn of Treasury bills in 2024, the third largest net buyer after JPMorgan Government Money Market Fund (US$53bn) and China (US$43.7bn) (see following chart and BIS Bulletin: “Stablecoin growth – policy challenges and approaches“, 11 July 2025).

The BIS report also estimates that stablecoins’ current market capitalization has doubled from US$125bn less than two years ago to US$255bn with the two biggest issuers, Tether and Circle, accounting for 90% of the market capitalisation.

The increased focus on T-bill demand through stablecoins is intresting for retail investors too. Instruments like SGOV offer similar exposure to the treasury bill market without the complexity of stablecoins, and they're already seeing decent inflows. The real question is whether this administration's push for low volatility can sustain itself if treasury issuance keeps accelerating.