Is Private Debt a Ticking Time Bomb?

Author: Chris Wood

With no sign as yet of a commencement of Federal Reserve easing, the longstanding view of this writer remains that the most likely casualty of the current monetary tightening cycle in America will be the so-called “alternative” asset class of private lending and private equity.

But problems are going to take time to show up because this area is essentially unregulated.

This means there are no pre-emptive provisioning pressures in stark contrast to commercial banking funded credit cycles.

It also remains a reality that most actors in this “private” area are incentivised to delay price discovery for as long as possible, as discussed here before (When Will the recession start? The answer may surprise you, 3 May 2023).

This writer, a former financial journalist, has also long been of the view that financial journalists who want to make a name for themselves should investigate into this area precisely because of the lack of easily available data sources.

Indeed the lack of transparency makes it a much more fertile ground for those willing and able to do the necessary hard work.

Finally, more probing articles are beginning to be written.

There was a Barron’s cover story on “shadow banking” in June which did a worthy job of outlining the overall exposures in this area without coming up with real smoking guns (see Barron’s article: “’Shadow Banks’ Account for Half of the World’s Assets – and Pose Growing Risks”, 2 June 2023).

Meanwhile the press has begun to report what this writer has been told anecdotally.

This is that most private equity companies opted against hedging interest rate exposure on the floating rate debt they took on for leveraged buyouts.

One explanation for this is that the private equity titans never expected interest rates to rise as much as they have.

This is not so surprising.

After all, the private equity boom has probably exploited more effectively than any other area of finance the “zero-interest era” presided over by former Fed chairman Ben Bernanke and his successors.

It is also the case that the focus of private equity operators has traditionally been on wringing operating costs out of a business with the cheap cost of money taken for granted.

Still the main reason the interest rate risk was not hedged is that the debt is taken on by the company that is bought by private equity in a leveraged buyout, not by the private equity firm itself.

That said, the pips are now beginning to squeak.

An estimate by Verdad Advisers quoted in a Bloomberg article in late June (“Hedging Failure Hammers Private Equity as Debt Costs Skyrocket”, 20 June 2023) put interest costs at the median private equity-backed company at 43% of Ebitda last year, which was six times as much as the median S&P500 company.

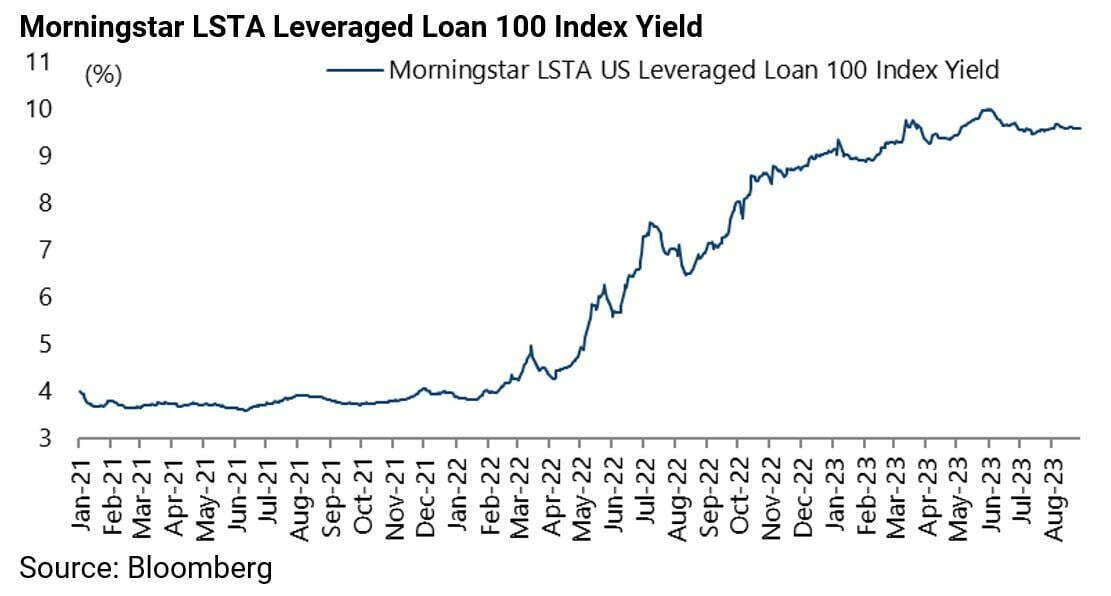

Meanwhile interest rates on the largest US leveraged loans rose to a peak of 10% in early June, up from 3.9% at the end of 2021, and are now 9.6%.

Credit Risk This Cycle is with Companies Not Consumers

All of the above helps explain why credit risk in this cycle in America is not primarily with households but with corporates.

Indeed American households’ debt to GDP is still well below 2008 levels.

The US household debt to annualised GDP ratio peaked at 98.9% in 1Q08 and has since declined to 74% in 1Q23.

What is the Riskiest Corporate Debt?

As regards corporate debt, there are three clear areas of exposure where credit has been extended to lower quality (in credit terms) companies.

They are leveraged loans, which total about US$1.4tn, private credit funds which total nearly US$1.5tn and high-yield bonds which total about US$1.7tn.

Out of these three areas, the least risky would be high-yield bonds because many companies have refinanced when bond yields were low.

This contrasts with leveraged loans which are floating rate as already discussed.

Many of them have been securitised and turned into collateralised loan obligations (CLOs).

The Financial Times reported last quarter that there were 18 debt defaults in the US loan market totalling US$21bn in the first five months of this year (see Financial Times article: “US junk loan defaults surge as higher interest rates start to bite”, 13 June 2023).

This is bigger than the total value for the whole of 2021 and 2022 combined.

As for private credit funds, this writer claims no expertise save to have been somewhat suspicious of the whole asset class since it emerged to exploit the vacuum left by heavily regulated banks post-2008.

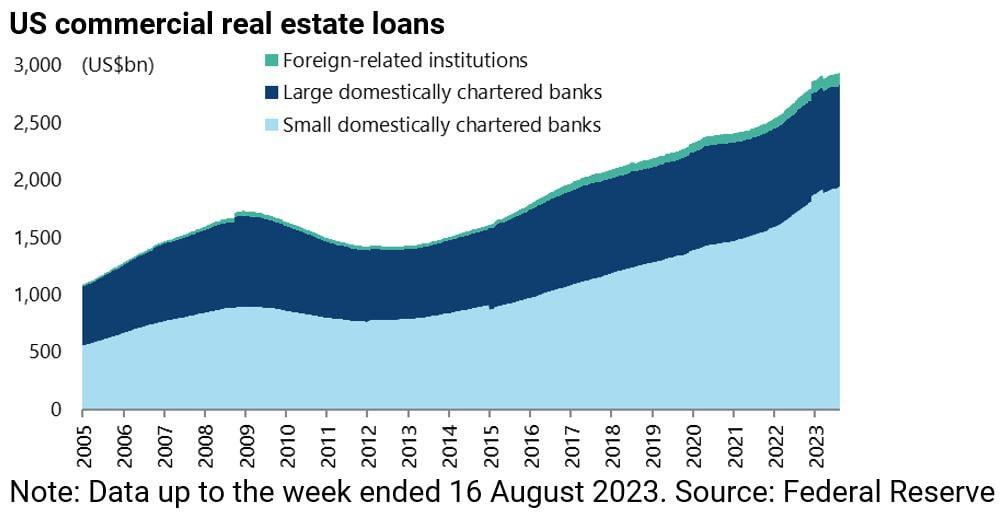

The final point on the unfolding US credit cycle is that, as previously discussed here (Are US small businesses OK?, 2 June 2023), commercial real estate is likely to be the area in coming quarters where the “private world” connects with the commercial banking funded world.

In this respect, the word is that US$1.5tn of commercial real estate loans are due to be refinanced in the next two years out of total US commercial real estate exposure of US$2.9tn, of which regional banks account for 66%.

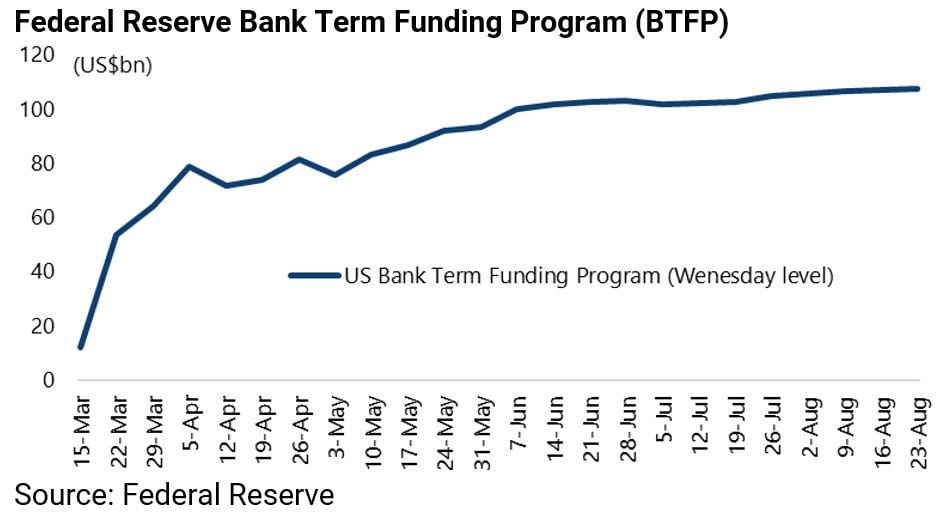

The regional banks index is up 20% from the lows triggered by the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) failure in March.

That should not surprise given the considerable help from the Fed.

The amount borrowed from the Fed’s Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) facility launched in mid-March has continued to rise, albeit at a slower pace.

Outstanding loans through the BTFP surged from US$11.9bn on 15 March to US$79bn on 5 April and have since risen further to a record US$107.4bn on 23 August.

Kicking the Can Down the Road

Meanwhile, in a stark departure from traditional prudential central banking principles, it should be remembered that the Fed has been marking collateral at par not at market value.

This is, of course, equivalent to warehousing a problem rather than marking it to market, which is another reason why the impact of monetary tightening will be delayed if not nullified.

Finally, as also previously discussed here (Here is your stock market roadmap for the rest of 2023 and 2024, 8 May 2023), SVB will likely be viewed by historians as the first hint of the troubles to come in the world of private equity, just as the failure of New Century Financial in April 2007 was the lead indicator for the resulting problems in subprime.