Is Argentina's Economic Experiment Working?

Author: Chris Wood

Argentina’s recently elected President Javier Milei made headlines when he made a speech at Davos in January accusing Western leaders of abandoning “the values of the West” (see Financial Times article: “Argentina’s Javier Milei says west ‘in danger’ in fiery Davos speech”, 18 January 2024).

This writer has to admit to being entirely sympathetic to the view expressed by the self-confessed anarcho-capitalist in terms of his critique of the Western world’s adoption of an increasingly collectivist approach that “inexorably leads to socialism, and therefore to poverty”.

Perhaps the key sentence from the speech was: “The case of Argentina is an empirical demonstration that no matter how rich you may be ... if measures are adopted that hinder the free functioning of markets, competition, price systems, trade and ownership of private property, the only possible fate is poverty”.

Such a view is clearly influenced by the writings of the late Friedrich von Hayek, this writer’s long favorite economist or, perhaps a better description is, political economist.

In this respect, Milei is now seemingly determined to implement the teachings of Austrian economics which conventional wisdom has long since dismissed as hopelessly impractical.

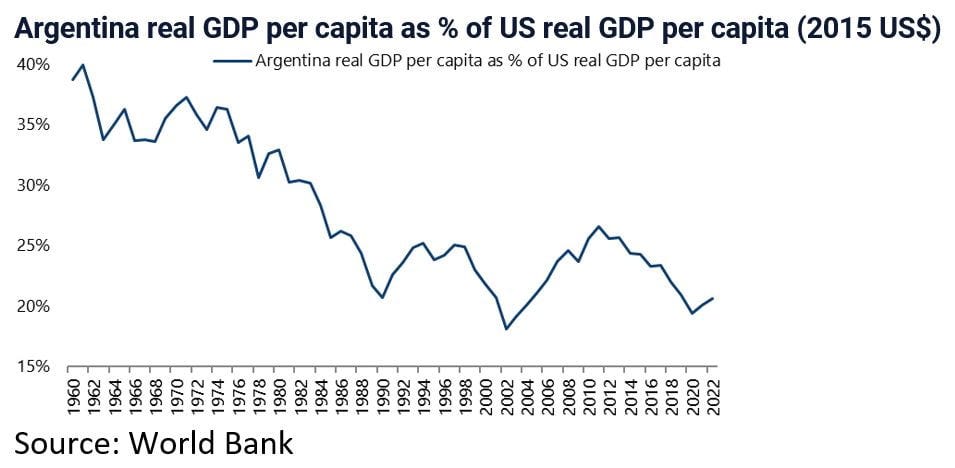

That this is happening in Argentina is no surprise since the country, once one of the world’s richest in the early 20th century, has suffered a dramatic fall from grace.

As one devaluation and default has followed after another, the country has suffered a dramatic decline from its formerly comfortable middle-income status.

Argentina’s real GDP per capita as a percentage of US real GDP per capita has declined from 40% in 1961 to 21% in 2022.

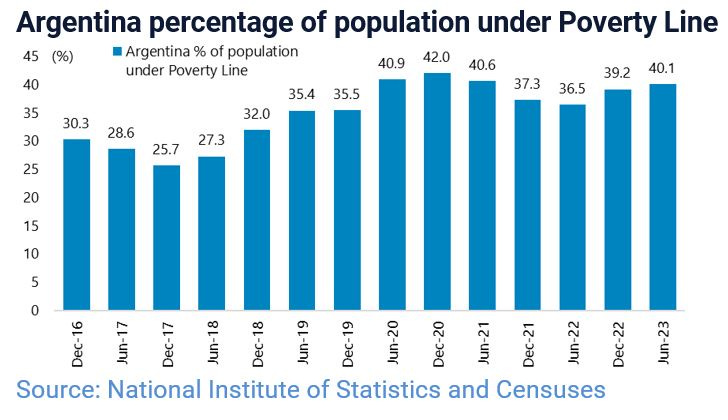

While 40.1% of the population are now estimated to be in poverty in 1H23, up from 36.5% in 1H22 and 25.7% in 2H17.

This is defined by the National Institution of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC) as those earning less than the monthly amount required to cover food and basic services, known as the total basic basket, which averaged 63,945 peso per month (US$300) in 1H23.

This macroeconomic debacle is the consequence of years of Peronist rule, a political party which has had a total contempt for the market-driven price signals beloved by devotees of Austrian economics.

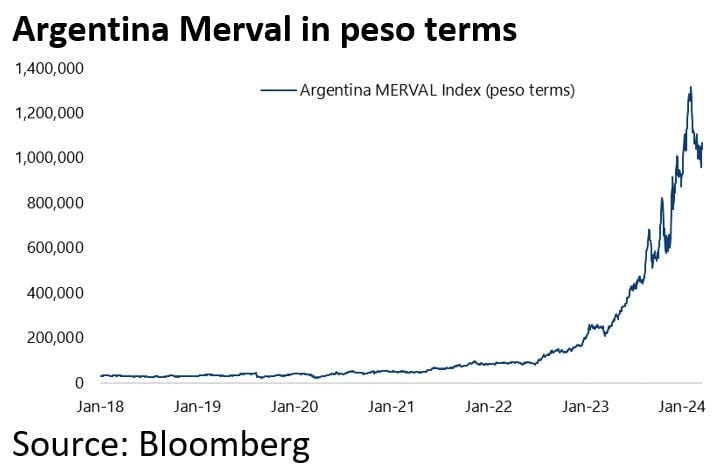

So disastrous have been their policies that the Merval Index fell 48% in US dollar terms the day after the Peronists won, surprisingly, the presidential primary election in August 2019 bringing an end to the reformist government of former President Mauricio Macri.

That caused big losses for the many foreign investors who invested an estimated US$38bn in Argentine stocks and bonds between 2016 and 2019 during the Macri government on increasing hopes that his reformist policies would prevail.

If Macri’s approach was gradualist, Milei aims at shock therapy.

In this respect, his best hope of success, in terms of keeping the population with him, is that he campaigned on the need to suffer if Argentina is to have any hope of solving its chronic economic problems.

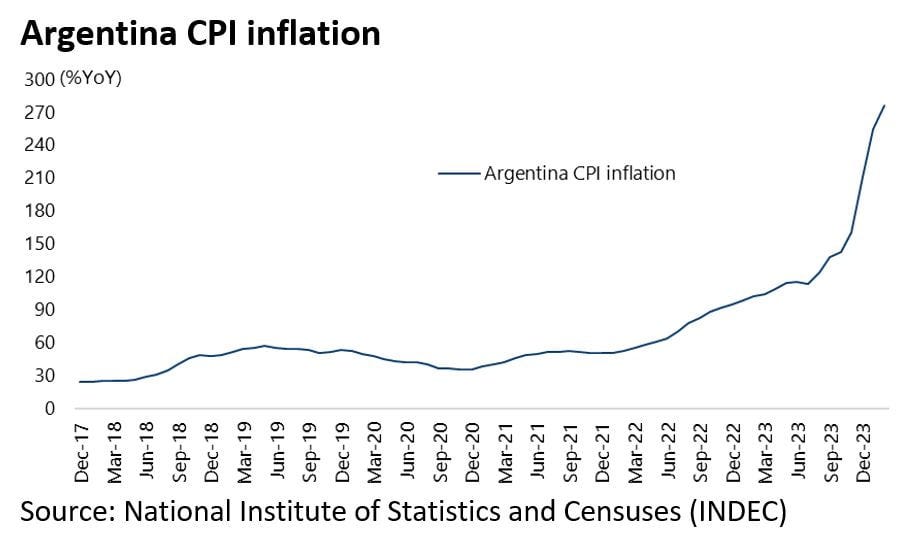

Inflation reached 211.4% YoY in December and was 276.2% YoY in February while Milei inherited a government with a negative net foreign exchange reserve position, estimated at around a negative US$7.2bn.

This came after the IMF’s US$7.5bn disbursement last August was used to pay maturing debt with the fund and other international institutions.

While the previous government spent US$2.8bn on pre-election spending financed with money printing and local debt.

The Milei Shock Approach

The clear consensus on the ground in Argentina is that the best hope for Milei to prevail is that he is an unconventional politician who has not promised the electorate goodies. Indeed he only entered politics three years ago.

The fact that he was elected in the second round of voting, with 56% of the vote, on such a radical agenda against the Peronist candidate Sergio Massa suggests enough of the electorate, and not just the middle-class, wants change.

His technical political problem is that his coalition, the La Libertad Avanza, established only in July 2021, does not control the legislature, though part of Macri’s coalition, Juntos por el Cambio, seems willing to support him.

The core of Milei’s shock approach is a proposed five percentage point cut in the fiscal deficit this year from 5% of GDP to zero, following a 54% devaluation announced in mid-December when he took power.

Meanwhile, a 17.5% tax levy on dollar purchases for imports of goods and services, up from the previous 7.5%, means the government is focused on accumulating dollars.

There are also the US dollar-denominated bonds issued by the central bank to indebted importers, known as the “Bond for the Reconstruction of a Free Argentina” (BOPREAL).

Importers are allowed to transfer the dollars they raise from selling these bonds in the secondary market to their foreign suppliers.

The central bank has so far sold US$7.5bn of such bonds since late December.

In this respect, a key variable to watch will be to monitor the presumed decline in central bank financing of the government.

On this point, the government announced in early January that it will raise US$3.2bn in US dollars in order to meet debt repayments via an issuance of 10-year bills to the central bank.

The “good” news is that the shock measures are already triggering a sharp slowdown in the economy.

For the sharper the slowdown the quicker inflation should fall after the initial devaluation triggered spike.

The view in the Argentine capital is that the next three to four months will be critical. If there is no sign of inflation declining by the middle of the year, then it is anticipated that there will be a widespread questioning of the reform programme.

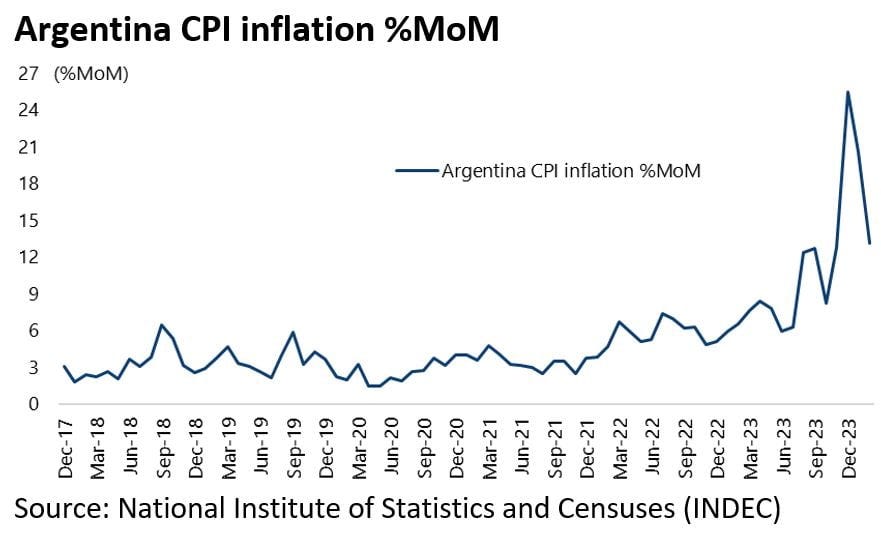

On this crucial point, CPI inflation has already slowed from a peak of 25.5% MoM in December to 13.2% MoM in February.

If that is the view of the locals, who are naturally somewhat skeptical given the history, the advice here to investors is to keep an open mind and monitor developments since the upside for local financial assets is massive if Milei prevails.

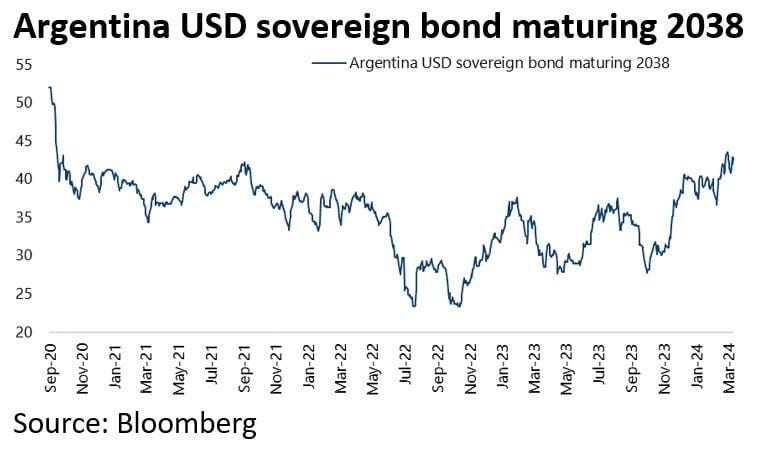

While both bond and stock markets rallied strongly on Milei’s surprise election victory in November, dollar bonds are still trading at only 40 cents on the dollar.

The Merval Index is still down 54% from its peak in US dollar terms reached on 12 December though it is up 6% in peso terms over the same period.

The era of “convertibility” between 1991 and 2001 was the last time Argentina enjoyed extended economic stability.

The peso was pegged to the dollar during this period before convertibility blew up when fiscal deterioration triggered an initial 29% devaluation to 1.4 in early January 2002 and a 74% devaluation to 3.86 in 1H02.

A positive point, if the macro can be stabilised, is that the private sector is as unleveraged as the government is financially extended.

In a classic example of what could eventually happen in the G7 world if current fiscal deterioration continues, Argentine corporate bonds have long since traded through the sovereign.

The best regarded Argentine corporate bonds have yields 1,000 basis points below the similar duration on government paper.

The other point is that during the last Peronist government the private sector was able to take advantage of an overvalued official exchange rate to import cheap capital goods.

This was particularly important for the energy sector where Argentina has a promising shale oil story which has the potential to reach crude oil production of 1m b/d by 2026.

Understanding The Classic Link Between Macro and Micro

As for the classic link between the macro and the micro, namely the commercial banking sector, the banks will have to focus on lending again if Milei prevails.

But for now an estimated 40% of their assets are in government bonds and lending to the central bank.

Meanwhile it is an important positive that the IMF has agreed for now to keep advancing Argentina funds to service its existing US$44bn loan programme, though it could hardly have done less given it kept funding the previous government despite its failure to stand by its commitments.

Argentina is the IMF’s largest debtor, with a total outstanding debt of US$43.2bn as of 15 March or 29% of total IMF credit outstanding.

On this point, the IMF technical staff agreed in mid-January to disburse US$4.7bn to Argentina as part of the existing loan programme.

What Can we Learn from Brazil?

Meanwhile, from a longer-term perspective, it is interesting to note the contrasting experience of Argentina and Brazil in recent decades in terms of the economic history.

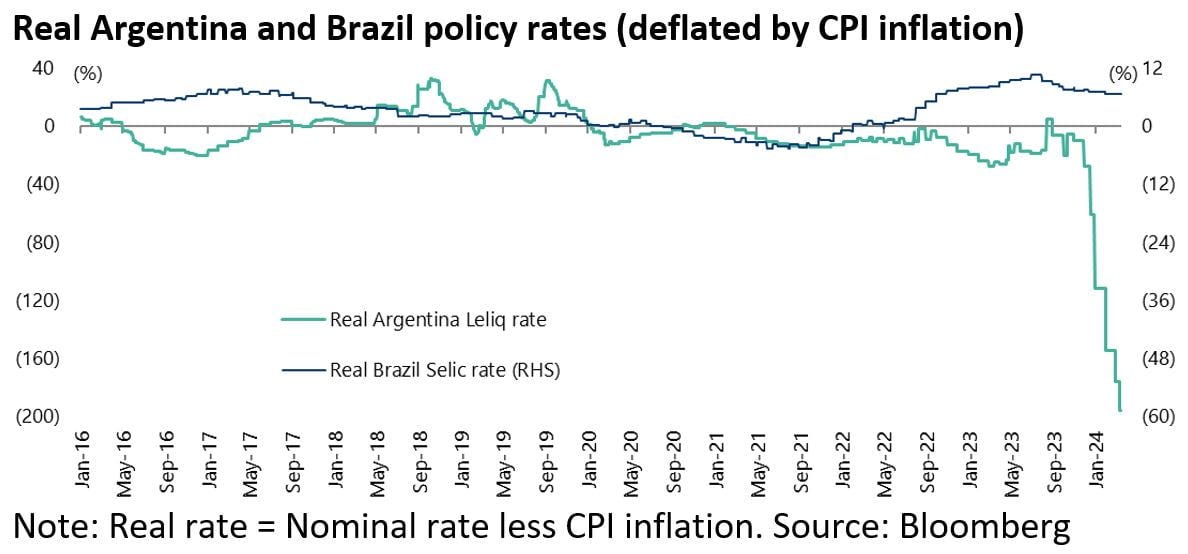

Brazil has stood out in the quanto easing era by maintaining high real interest rates.

But this has been a feature of the country for decades.

The result has been a system where Brazilians have been prepared to keep their money at home since they were paid a decent return on their capital though, admittedly, the availability of high real rates meant that bonds have usually been favoured over stocks as continues to be the case today.

If creditors have been favoured over debtors in Brazil, the exact opposite has been the case in Argentina whose historical experience has been the precise opposite; namely the absence of real interest rates.

The result has been wealthy Argentinians keeping as little of their funds in the country as possible save what they need to conduct business.