If Japanese Bond Yields Hit 1%, it Could Shake the US Treasury Market

Author: Chris Wood

The key issue for world markets remains when monetary tightening is going to bite in the US economy.

If the downturn in M2 growth in the recent past remains the most dramatic on record, the base effect is still critical given the scale of the expansion in broad money supply in 2020.

This is why, as previously discussed here (A pronounced Slowdown in Inflation is Coming, 14 September 2023), the US M2 to nominal GDP ratio is so important to monitor.

Based on the 2Q23 GDP data, this is now 4.4% above the pre-Covid trend, down from a peak of 27% above trend reached in 2Q20.

When this ratio declines below trend is when monetary tightening will really start to bite.

Higher Rates are Actually Helping Corporate Balance Sheets..For Now

Meanwhile it remains a reality that monetary tightening has not impacted many large corporates in America with access to the bond market, because they locked in their financing costs by terming out their debt when bond yields were very low a few years ago.

This dynamic can be illustrated by the way that nonfinancial corporates’ net interest payments have declined based on the latest national accounts data.

If locked in financing costs is one aspect behind this decline, another is the dramatic increase in returns earned on companies’ cash balances thanks to Fed tightening.

US nonfinancial corporates’ net interest payments as a percentage of profits after tax declined from 19.2% in 1Q22 to 12.3% in 2Q23, the lowest level since 2Q65 (see following chart).

In absolute terms, net interest payments have declined by 31% YoY from an annualised US$292.4bn in 1Q22 to US$201.9bn in 2Q23, the lowest level since 3Q06.

Japan - An Interest Rate Policy on the Ropes

Meanwhile, if Fed tightening has now been ongoing now for 18 months following 525bp of rate hikes, the situation is very different in Japan.

The monetary tightening that dares not speak its name.

That seems as good a description as any of the rather bizarre manner in which the Bank of Japan further adjusted its yield curve control (YCC) policy in late July.

The Japanese central bank announced that, going forward, it would effectively allow the 10-year JGB yield to trade up to 1%, well above the previous cap of 50bp.

This was, on the face of it, a significant change in policy.

Yet BoJ Governor Kazuo Ueda was at pains to play down the change stating in the post-meeting press conference that it was not expected that the long-term yield would reach 1% now but “we have capped it as a precaution”.

1% on the 10-year JGB is, as previously discussed here (Will The Stars Finally Align For Japanese Stocks?, 12 April 2023), the level of yen bond yield where it starts to make sense for Japanese financial institutions, such as life insurers, to begin repatriating capital from abroad.

This could potentially set off tremors in G7 government bond markets, most particularly in the US Treasury bond market.

The interesting point is that markets did not react much to the change in policy even though most economists were not expecting an adjustment of the policy at that BoJ meeting.

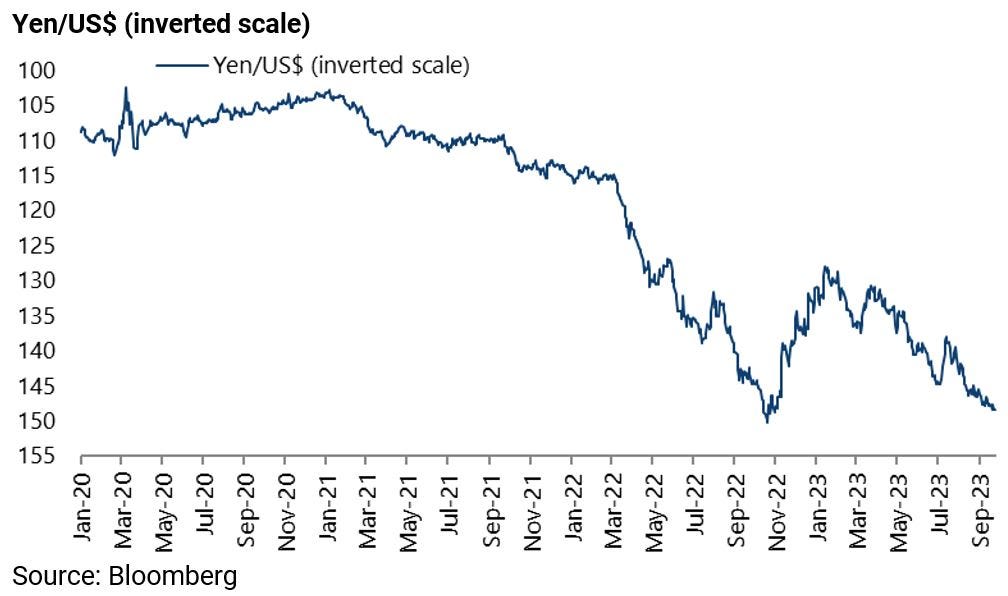

Indeed the yen did not even rally, while the Japanese currency is now at a level against the US dollar 6% lower than where it was prior to the BoJ announcement on 28 July.

This reflects the wide interest differential between the two currencies.

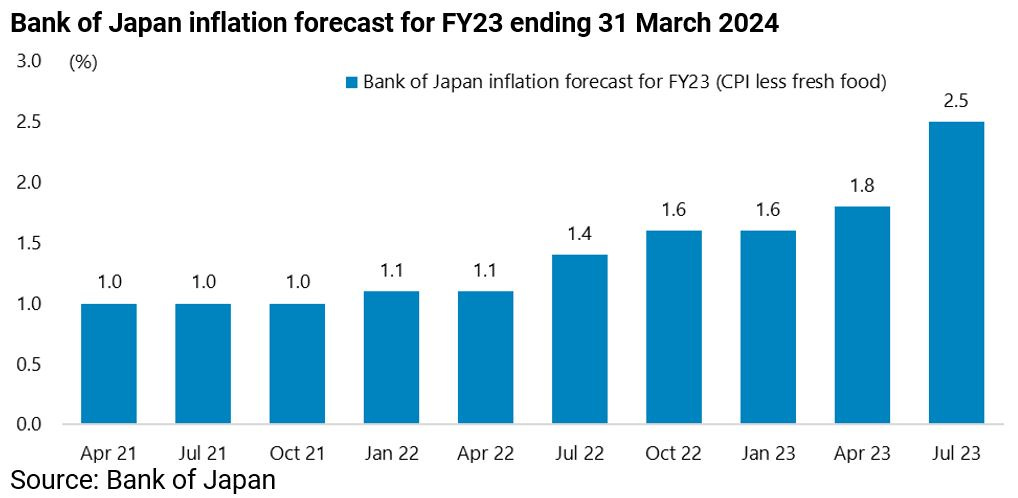

Meanwhile one reason for the timing of the YCC adjustment in July is that the BoJ increased its core CPI inflation forecast for this fiscal year ending 31 March 2024 at that meeting by a significant 0.7 of a percentage point from 1.8% to 2.5%.

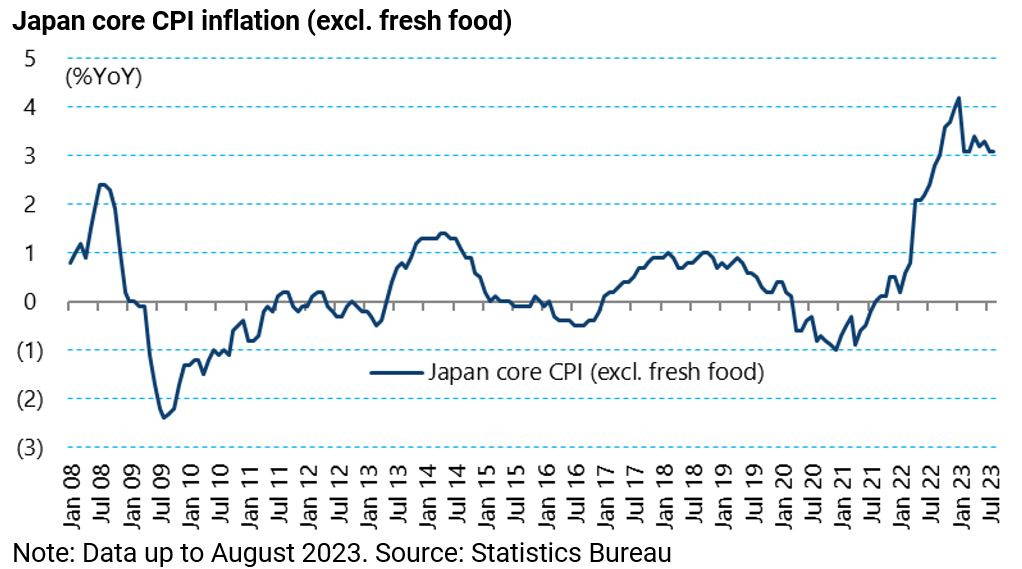

It is also the case that core CPI inflation was 3.1% YoY in August, marking the 17th consecutive month it has been above the 2% target.

Still despite such statistical evidence of rising inflationary pressures, the BoJ has continued to maintain the complementary deposit facility rate at a negative 0.1% at its latest meeting held at the end of last week.

This must be extremely irritating for Japanese banks who would like to see the end of negative rates for the same reason that European banks have celebrated the exit from negative rates.

On this point, the BoJ thinking seems to be that a move out of negative rates should only come after an abandonment of YCC.

The reality is that the move out of negative rates should already have happened months ago.

For now the base case remains that a further normalisation of Japanese monetary policy is coming sooner rather than later.

Meanwhile the 10-year JGB yield is currently trading at 0.744%, having reached 0.756% last Friday, the highest level since September 2013.