How Could Geopolitics Influence The Election?

Inflation, Oil, Ukraine and Israel

Author: Chris Wood

Financial media continues to focus on such matters as Fed policy and the endless chatter of Fed governors.

But the newsflow in the financial sphere in many respects pales into insignificance compared with the tectonic shifts going on in geopolitics.

The base case of this writer is that financial markets are useless in discounting geopolitics until events become impossible to ignore.

And while it is entirely natural for markets to hope that geopolitical tensions are peaking, be it in the Middle East or as regards the Russia-Ukraine conflict, that is not the view of this writer.

Such a view is perhaps less controversial in the case of Ukraine.

With the US Congress having finally agreed in late April on the US$61bn further funding for Ukraine, this ensures that the war will continue and, unfortunately, more people will be killed on both sides.

For what is clear is that Ukraine can only continue to wage the war with the benefit of external funding, which is why if the aid had not been provided the likelihood would have grown of some diplomatic solution based on the current reality that Russia occupies the eastern provinces of Ukraine and Crimea.

Will Ukraine Try to Trigger direct NATO Involvement with Russia?

Still, with the aid provided, the war can continue, which raises the scary but growing prospect of a direct confrontation between Russia and NATO forces.

It is also the case that Ukraine has every incentive to try and trigger more direct NATO involvement, most particularly prior to the US presidential election in November given Donald Trump’s stance on the conflict.

Meanwhile, a seemingly well-sourced Reuters article reported in May that the recently re-elected Russian President Vladimir Putin is ready to negotiate a ceasefire that “recognises the current battlefield lines”.

The Reuters article cited four Russian sources, three of which were “familiar with discussions in Putin’s entourage” (see Reuters article: “Exclusive: Putin wants Ukraine ceasefire on current frontlines”, 25 May 2024).

It is no surprise that Moscow is willing to talk since it appears to be prevailing in the conflict on the ground, a development reflected in the abovementioned decision by Congress to agree to more military aid to Ukraine.

Still the worrying dynamic is that the more Russia prevails, which has to be the base case given its overwhelming military superiority in terms of number of soldiers, the greater the incentive for the Ukraine government to take action designed to trigger NATO involvement, such as attacking Russia’s nuclear ballistic missile early warning radar network with two such radar facilities reportedly having been attacked by Kyiv’s drones in late May (see, for example, Newsweek article: “Map Shows Ukraine's Record-Breaking Hits on Russian Nuclear Warning Sites”, 28 May 2024 and Bloomberg article “Ukraine Claims Second Hit on Russian Missile Early-Warning Radar”, 27 May 2024).

The above-mentioned Reuters article also mentioned that, while hoping for a deal, Moscow is also preparing for a protracted conflict.

In this respect, the article reported that the appointment in mid-May of economist Andrey Belousov as Russia’s defense minister has been viewed as placing the Russian economy on a permanent war footing.

Anyone with any understanding of history will appreciate that Russia’s propensity for enduring long slogs of a military nature should not be underestimated.

Ukraine Aid is Exposing Rifts in the Republican Party

Meanwhile, the drawn out debate over aid to Ukraine in Congress earlier this year exposed the ideological rift in the Republican Party over this issue.

The interesting point is that Donald Trump has, not yet at least, broken with House of Representatives Speaker Mike Johnson who effectively enabled the Biden administration legislation on Ukraine funding to pass even though Trump is close to Johnson’s chief critic in the Republican Party, namely Marjorie Taylor Greene.

Given Trump’s longstanding opposition to the Biden administration’s policy on Ukraine, the interesting question is why Trump has refrained so far from a more aggressive stance.

It may, simply, be that the 45th president is choosing not to escalate a divisive issue in an effort to preserve Republican Party unity in the lead up to the November election.

Middle East Tensions are a Risk to a Democratic Victory in November

Meanwhile, if the base case is now that the Russia-Ukraine conflict will continue in the months leading up to the November presidential election, the other concern for the Biden administration remains that renewed Middle East tensions trigger a further rally in the oil price at a time when the inflation issue is not yet fully dealt with.

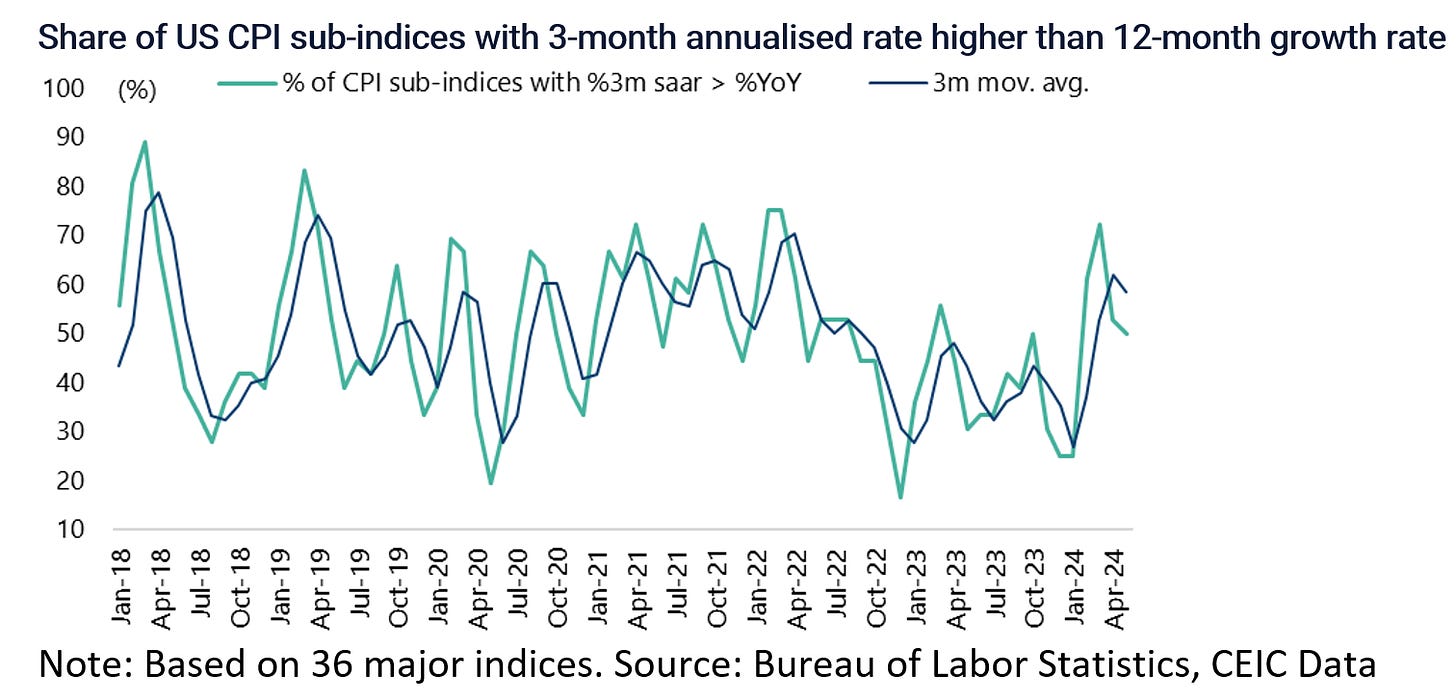

In this respect, one way of illustrating ongoing stubbornly inflationary pressures is the percentage of CPI sub-indices where the 3-month annualised inflation rate is running above its 12-month rate.

This was 50% in May, though down from 72% in March.

Are Israeli tensions towards Iran About to Escalate?

Returning to the Middle East, this writer would personally be astonished if the world has witnessed the last of Israel’s actions against Iran, though Israel can clearly bide its time in terms of when to implement a more telling response, with the obvious high beta play an Israeli attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities.

Clearly, such a move before the US Presidential election would be extremely provocative, given the likely impact on oil prices and related financial markets.

But that does not mean it can never happen.

The lesson from the outbreak of Middle East tensions since the 7 October attack of Hamas on Israel is that the Biden administration has a hard time controlling the administration of Benjamin Netanyahu.

The other point is that while Netanyahu is a divisive figure in Israel in terms of domestic politics, as regards the issue of Iran and indeed the continuing presence of Hamas in Gaza, there seems to be a widespread consensus in Israel that the Hamas attack last October represented an existential crisis to the state of Israel.

In this respect, Netanyahu would seem to have the support of most of the Israeli electorate for the military strategy pursued since 7 October.

Meanwhile, Netanyahu’s whole political career suggests he has always been strongly opposed to the “two-state solution” still being pushed by Washington and London.

In this writer’s view, any realistic chance of such an outcome probably ended with former prime minister Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination in November 1995.

How Will the Gulf Countries Respond to Israel?

Meanwhile, amidst the escalating tension between Israel and Iran, and the continuing backing of Israel by Washington despite the growing criticism of Israeli behaviour on the streets and campuses of America, an interesting question is what will be the response of the Gulf countries.

The sense of this writer is that, ideally, they would like to keep a foot in both camps.

But that may become a stance difficult to maintain.

What is self-evident for now is that the relationship between the Gulf states and Washington is not as close as it once was.

Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE joined the BRICS group as of 1 January.

While Saudi and the UAE are cooperating with Russia, in the context of OPEC plus, to keep 2.2m barrels of oil a day off the market.

The point of all of the above is simply to note that the tectonic shifts are occurring of at least as great an importance as the last big geopolitical development, namely the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

But while that event provided a peace dividend, on the then popular albeit erroneous “end of history” theme, the opposite is now the case as reflected in the surge in defense spending globally.

Global military spending rose by 6.8% YoY in real terms to a record US$2.4tn last year, the biggest annual increase in 15 years, according to the latest annual survey by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.