Has China's Property Market Bottomed?

Author: Chris Wood

Has China’s property market bottomed?

There has been a noticeable pick up in residential property transactions in the past two months following the easing measures announced by Beijing in late September.

Sheng Laiyun, deputy head of the National Bureau of Statistics, said in a press conference on 18 October that, based on preliminary statistics from various market operators, residential transactions in floor space terms during the National Day holiday in the first week of October increased by 102% WoW for new homes and 205% for secondary homes.

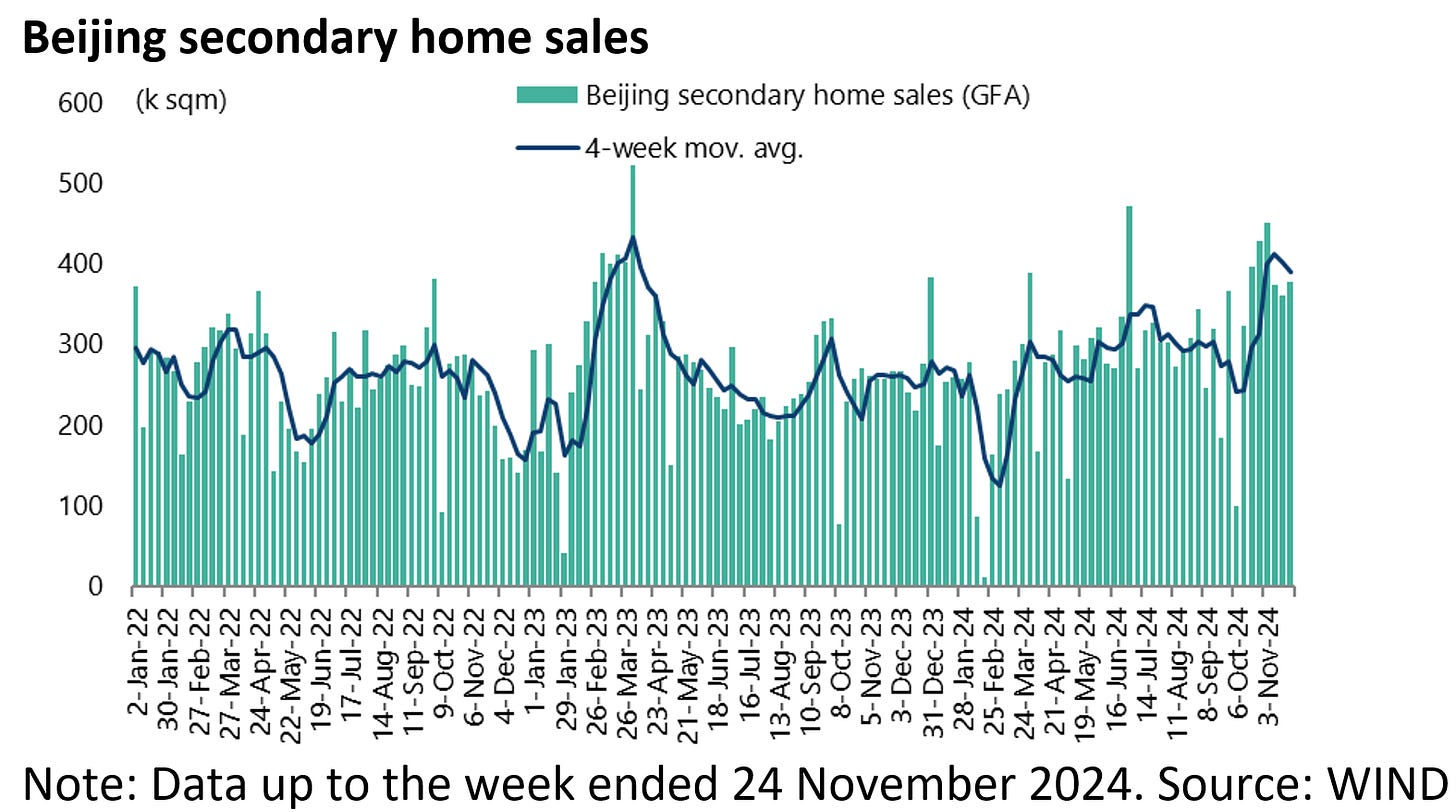

Beike Research Institute also reported that the average daily transaction volume for secondary homes among Beike’s outlets in Shenzhen surged 228% in the period from 30 September to 20 October compared with the sales in the previous three-week period. While secondary home sales volume in Beijing rose by 50% YoY in the first four weeks of November, according to WIND.

This renewed activity raises the potential at least for a stabilisation in the market. Normally a pickup in transactions would precede any stabilization in prices.

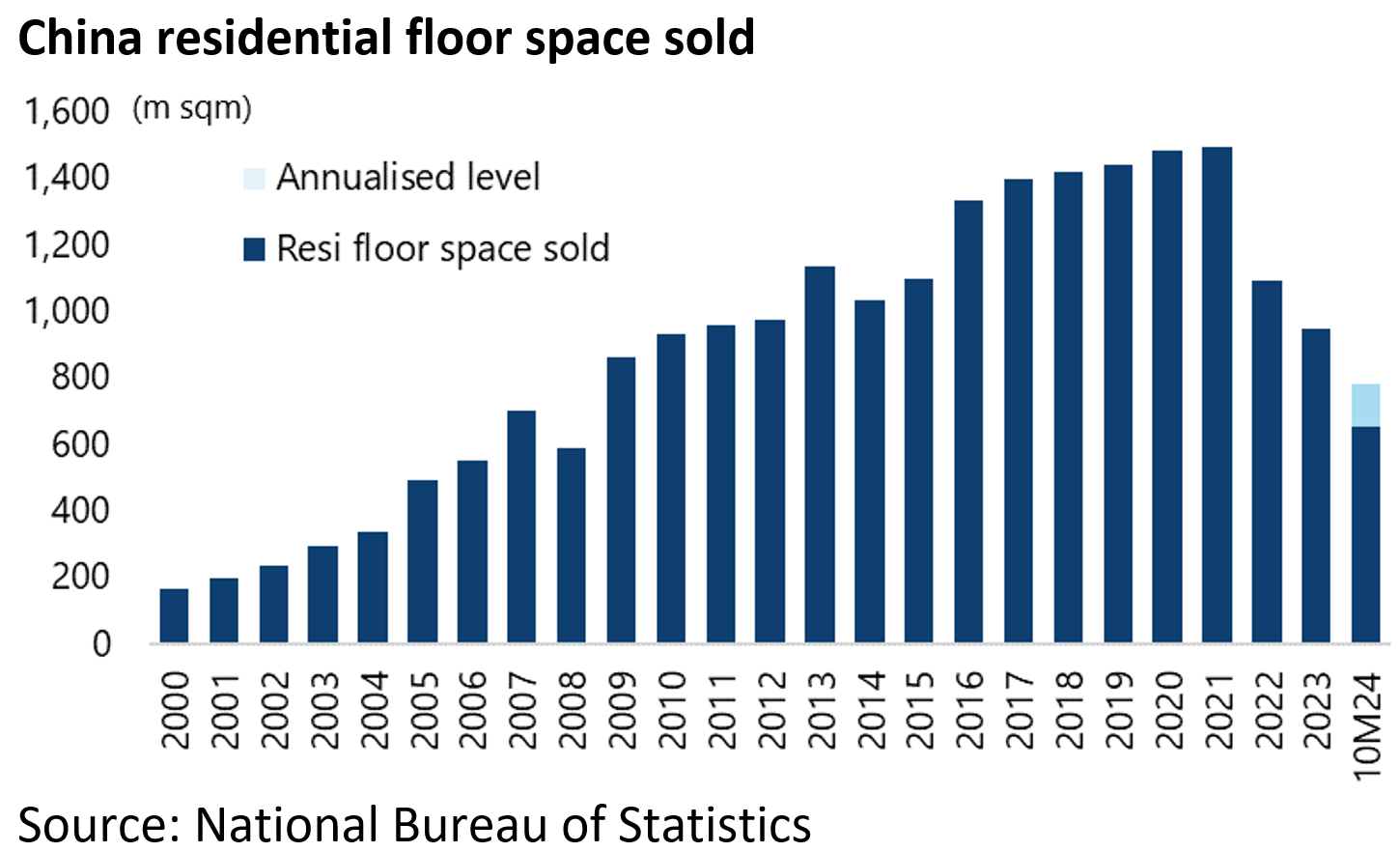

The base case remains that natural fundamental upgrading demand in China is about 700-800m sqm a year, or about half the level of peak home sales which was around 1.5bn sqm per year in 2021.

Residential property sales totaled 654bn sqm in the first ten months of 2024, or an annualised 781bn sqm.

Secondary Market Gaining Steam, Primary Market Still Sluggish

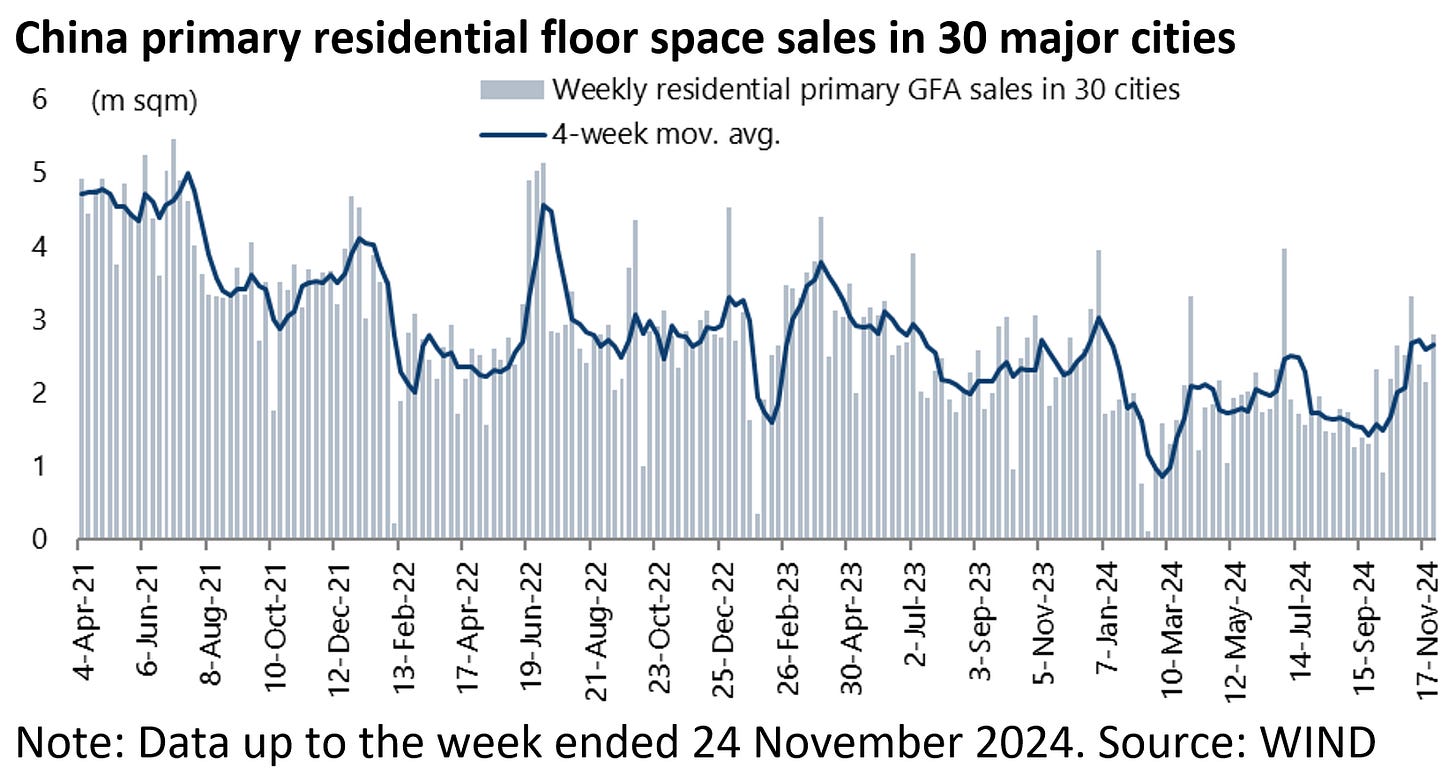

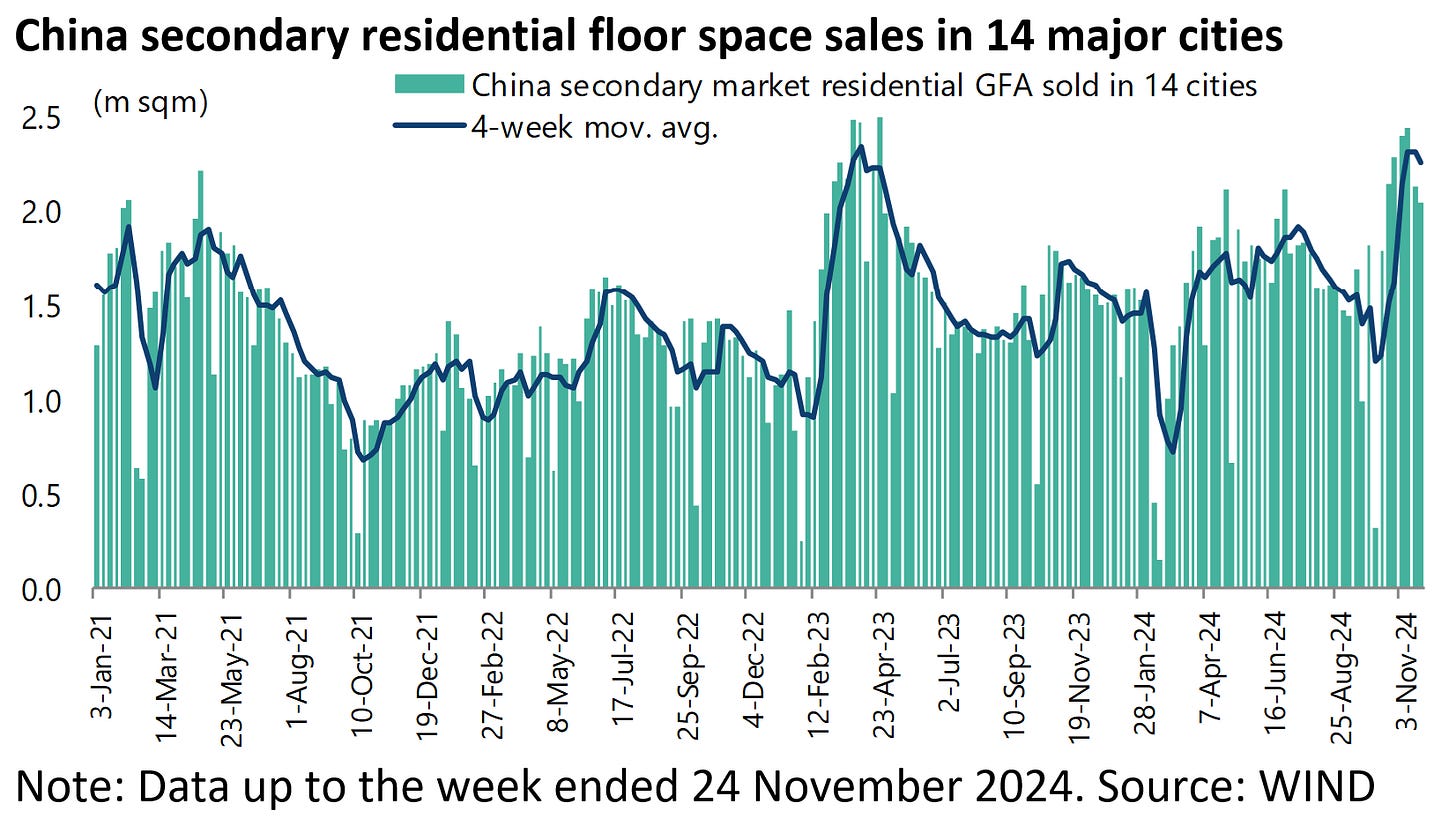

Meanwhile, activity in China’s property market continues to move from the primary market to the secondary market.

Thus, primary residential floor space sales in 30 major cities rose by 19% YoY in the four weeks to 24 November but are still down 29% YoY year-to-date.

By contrast, weekly secondary residential sales volume in 14 cities rose by 35% YoY in the four weeks to 24 November and is now up 2% YoY in the year to 24 November.

This move from primary to secondary is what should be expected in any residential property market as it matures.

But in China the demand for secondary has been given an extra boost by the risk of uncompleted projects because of the cashflow crunch facing developers, most particularly private sector developers many of whom are essentially bust.

On that point, the Chinese government announced in October a doubling in the amount of money allocated to the so-called “white list”.

This is the process whereby banks are essentially required by the relevant local government to finance the completion of a project once it has made it on to the list.

The Minister of Housing and Urban-Rural Development Ni Hong said in a press conference on 17 October that China plans to expand bank credit lines for the unfinished housing projects on the “white list” to Rmb4tn by the end of 2024.

This will nearly double the amount to be provided.

As of 16 October, bank loans approved for “white list” housing projects had reached Rmb2.23tn, according to deputy head of the National Financial Regulatory Administration Xiao Yuanqi (see Xinhua news article: “China unveils new measures to stabilize housing market”, 17 October 2024).

The “white list” remains far from the ideal response to the uncompleted project issue, most particularly as the policy is implemented via local governments not by the central government top down.

But it is certainly better than nothing. It is worth noting again that the scheme is deliberately designed to approve lending to specific projects to avoid the risk that financially struggling developers deploy the funds elsewhere.

Still one problem with the “white list” is, apparently, that if a property project is not on the list the development has scant hope of being financed at all.

Housing Market Psychology is Improving

Still the recent pickup in activity suggests that perceptions of the residential market have now changed given the positive signal given on property from the Politburo meeting on 26 September which, crucially, President Xi Jinping attended.

A formal commitment was made in the meeting to stabilise the property market. It is also the case that with prices down in reality by as much as 40% or more from the peak in many major cities, or way more than suggested by official price data, buyers may have started to think that prices are near to bottoming.

The other relevant positive is that, despite those price declines, there has been no surge in bad mortgage debt as yet.

This reflects the fact that mortgage lending was done on a conservative basis in China with a maximum loan deposit ratio during the boom of typically only 50%.

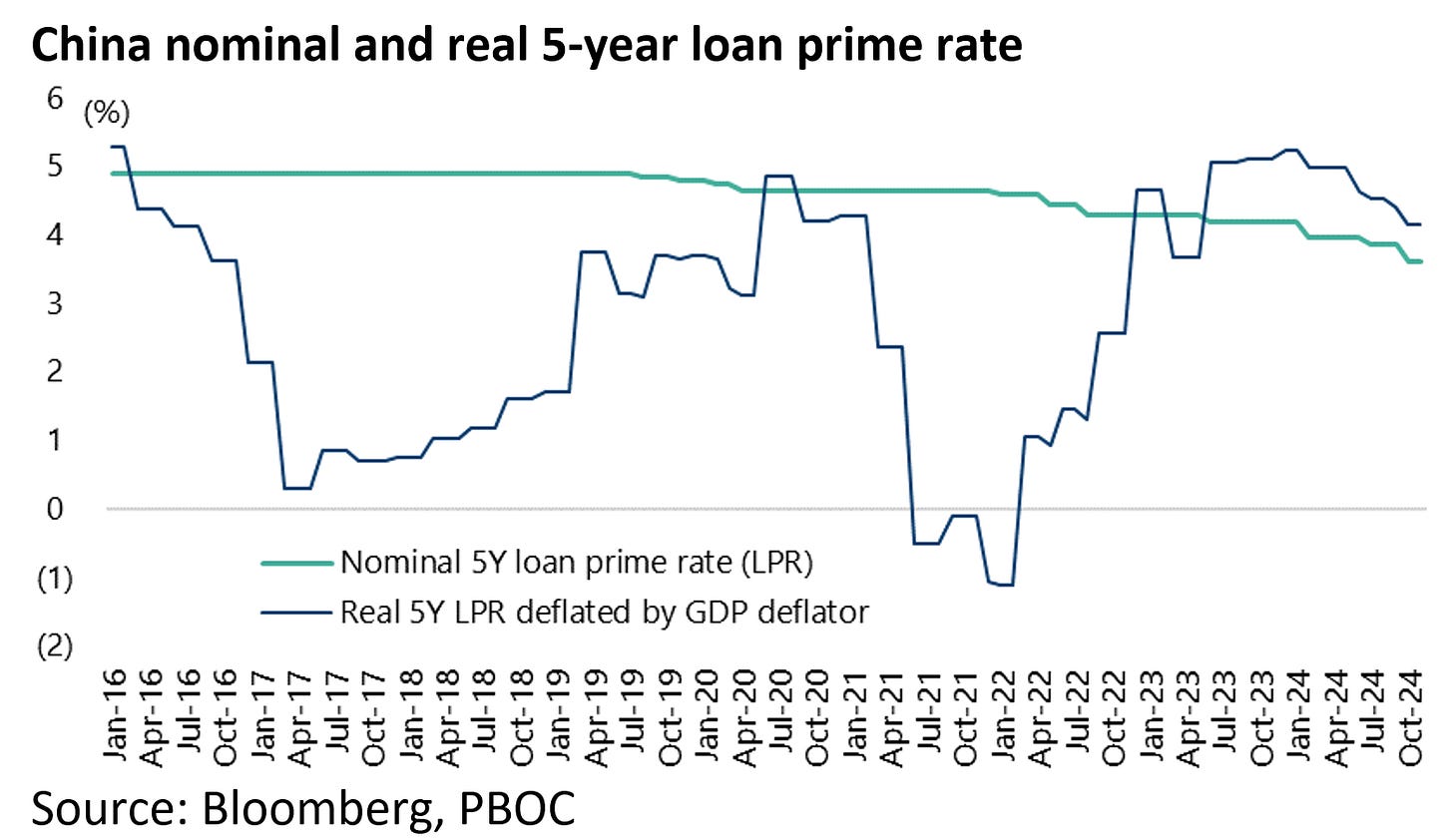

Meanwhile, the five-year loan prime rate (LPR), the key reference rate for mortgages, is now 3.6%.

If the real five-year LPR, deflated by GDP deflator, is still a positive 4.1%, in nominal terms at least the rate has declined by 105bp since the start of 2022.

Meanwhile, President Xi’s main priority, in terms of recent easing measures, has probably been to address the issue of unpaid wages and unpaid receivables at the local government level as a result of the slump in land sales.

This is why Beijing announced a central government local government debt swap in November designed to give local governments more financial room for manoeuvre.

The estimate is that replacing the so-called hidden local government debt with government bonds will save Rmb600bn (US$82bn) in interest payments over five years for local governments.

This is money that can now be spent elsewhere.

Still this is far from the bazooka stimulus some investors, unrealistically, had been hoping for.