As China Loses Global Investors, India's Time May Have Come

Author: Chris Wood

As many global investors have now decided that China is “uninvestable”, it increasingly looks like India’s time has come both as a stock market and as an economy.

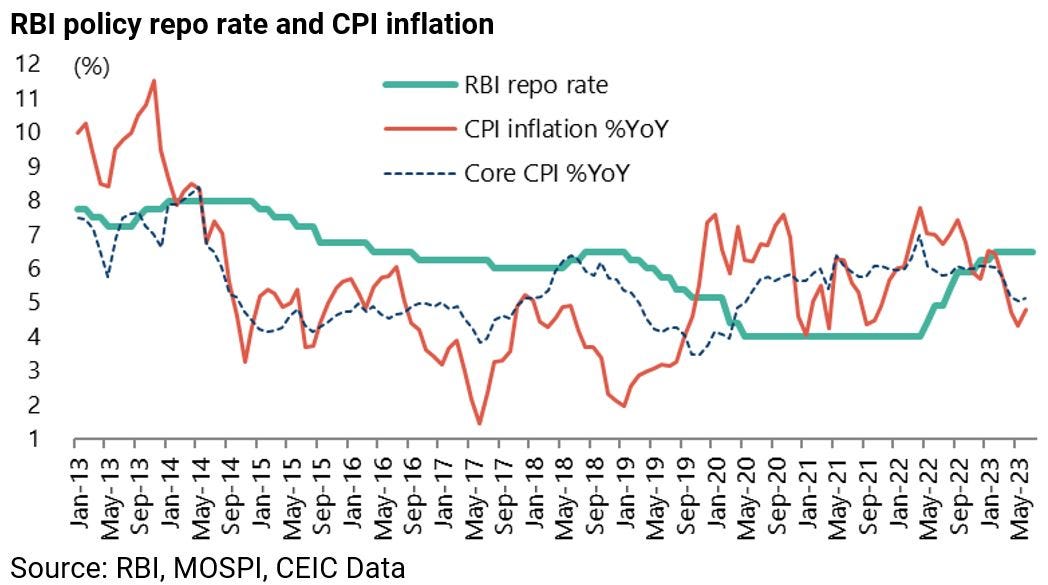

From a stock market standpoint, the most obvious positive is that the monetary tightening cycle is all but over with inflation falling in recent months.

Headline and core CPI inflation have declined from 6.5% YoY and 6.1% YoY in January to 4.8% YoY and 5.1% YoY in June, while the Reserve Bank of India has kept its policy repo rate unchanged at 6.5% since February after 250bp of rate hikes since May 2022.

Meanwhile the political season is approaching in India with a general election due to be held next May.

The overwhelming view in India remains that Narendra Modi and the BJP government will be re-elected, albeit perhaps with a reduced majority.

In the 2019 election the BJP won 303 of the 543 elected seats in the Lok Sabha.

In a national election, as opposed to one of India’s numerous state elections, the electorate votes on the big issues and here the dramatic changes wrought by Modi after ten years in power have been phenomenal.

One is the transformation of physical infrastructure, where the fiscal deficit has in recent years been primarily spent on investing in infrastructure and not on entitlements.

The result is that the huge deficiencies in infrastructure, so visible when this writer first visited the country on a business trip back in the late 1990s, have now been largely addressed.

The government’s stated aim is to reduce the cost of logistics from the current 14-16% of GDP to 9% in the next three years.

If the physical infrastructure upgrade is one big positive change, another which impacts everybody is the distribution of targeted welfare via the use of technology and the successful exploitation of combining the Aadhaar electronic ID card developed during the previous Congress government with the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) scheme.

This transfers subsidies and cash benefits directly to the people through their Aadhaar-linked bank accounts. Then there is the massively successful Unified Payments Interface (UPI).

The UPI, set up in 2016, is a digital payment system that allows instant interbank fund transfers via mobile apps.

Transactions on it are now running at 9.3bn a month in volume terms and Rs14.8tn (US$179bn) in value terms. UPI transactions totaled Rs139tn (US$1.7tn) last fiscal year.

The practical result of DBT has been a dramatic decline in leakages in the distribution of welfare which helps explain why support for the BJP, traditionally a party of small businessmen and traders, has spread to the urban poor and rural constituencies.

Other life-transforming changes under Modi include the construction of public lavatories in villages and the provision of running water.

Clearly, the negative rap on the Modi government is that it is exploiting ethnic divisions to run on a “Hindu supremacist” agenda.

If this explains the continuing negative coverage of the BJP government in much of the Western media, the reality is that there has been a massive surge in popular aspirations since Modi was first elected in 2014 and also a related massive increase in India’s self-confidence as a country.

China and Russia's Losses are India's Gains

There is, for example, now much fashionable talk, which is no longer completely far-fetched, of India becoming the major beneficiary of production being moved out of China in the next ten years.

Certainly Apple’s CEO Tim Cook, who has as urgent a need to diversify out of China as anybody given the ongoing geopolitical tensions, went to great lengths to highlight India in his most recent quarterly earnings call in May.

He mentioned the country no less than 20 times, not only as regards to its importance as a growing consumer market for iPhones but also as a growing source of production (see Bloomberg article: “Apple CEO Sees India at Tipping Point as China Pivot Quickens”, 5 May 2023).

The other way India’s increased national self-confidence has been manifested on the world stage in the past year and more is as regards its purchasing of cheap Russian oil.

Despite initial pressures from Washington on Delhi, the Modi government has been consistent in its public stance that it will continue to act in its own national self-interest, which is to buy cheap Russia oil.

This stance was helped by the understanding that, as the next big domestic market for American companies such as Apple to target, it makes no strategic sense for Washington to pick fights with both Beijing and Delhi.

India’s purchases of cheap Russia oil continue.

India’s oil imports from Russia have grown from 1.12m tonnes in April 2022 to 8.93m tonnes in May. And these transactions are now in rupees.

Stock Market Update: Is is Cheap?

As for the Indian stock market, it essentially traded sideways during the monetary tightening cycle which allowed earnings growth to catch up with valuations, though a rally got under way last quarter.

From a valuation standpoint, the one-year forward PE at 18.9x is now above the 10-year average of 17.4x.

If Monetary Tightening is Over, Its Game On

Meanwhile if monetary tightening is over, with rate cuts coming either later this year or next year, there is no obvious near-term trigger for a sell-off save for a bout of Wall Street-correlated external risk-off action.

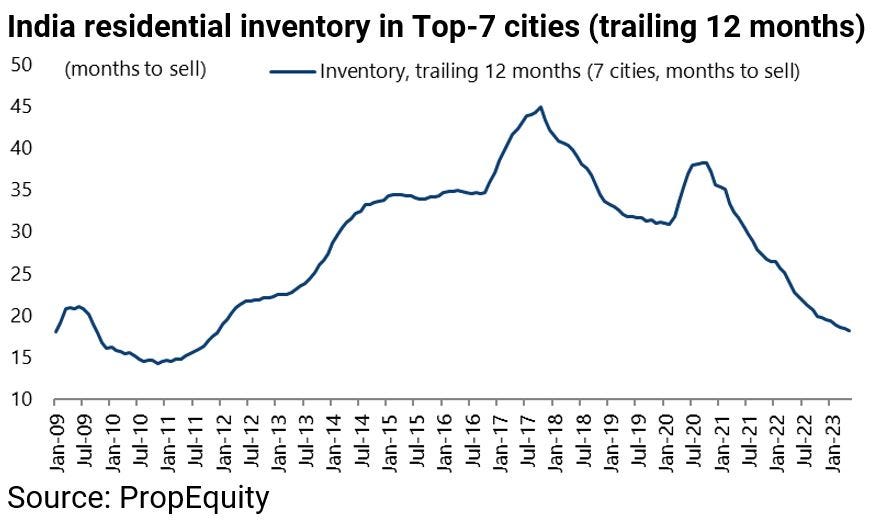

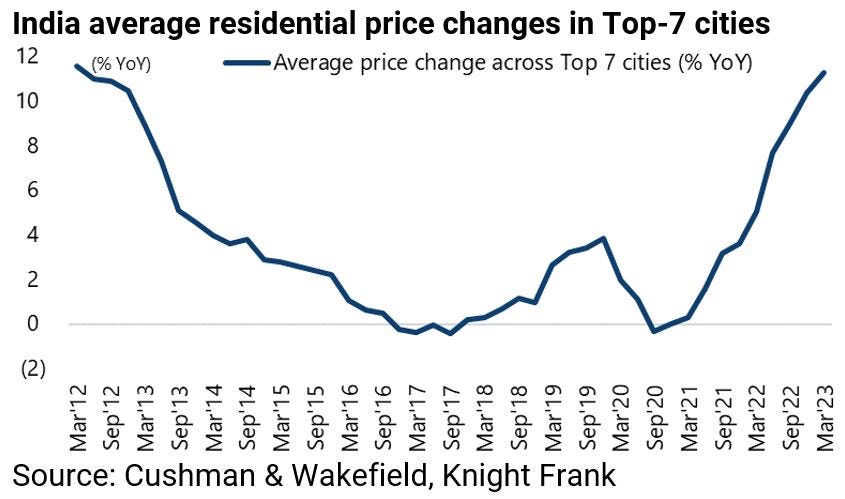

As for the domestic drivers of economic growth, hopes continue to build for a capex cycle while the residential property market has now entered the third year of an upturn.

This property cycle should run for at least another three to four years given the seven-year duration of the preceding downturn and the resulting pent-up demand.

Housing volumes are expected to grow by an annualised 15% over the next few years given that they only grew by an annualised 2% between 2010 and 2022.

Meanwhile property inventory continues to come down and property prices to rise.

Residential inventory for the top-7 cities has declined from a peak of 45 months in October 2017 to a 11-year low of 18 months of sales in May.

While residential property prices across the top seven cities rose by an average 11.3% YoY in 1Q23, the highest growth rate since 1Q12.

India is on the Brink of a Major CAPEX Cycle

If the residential property story remains straightforward, with affordability not really challenged by the recent monetary tightening cycle, the other positive is the accumulating evidence that India could be on the brink of a major capex cycle.

The macro evidence for this is that gross fixed capital formation has begun to move up as a percentage of nominal GDP, having been in a downtrend since FY09.

The gross fixed capital formation to GDP ratio declined from a peak of 35.8% in FY08 to 27.3% in FY21 and has since risen to 29.2% in FY23.

Meanwhile the bottom-up evidence is that private sector new project announcements, a good leading indicator, are surging.

Private new project announcements have risen from Rs5.1tn in FY21 to Rs25.7tn in FY23.

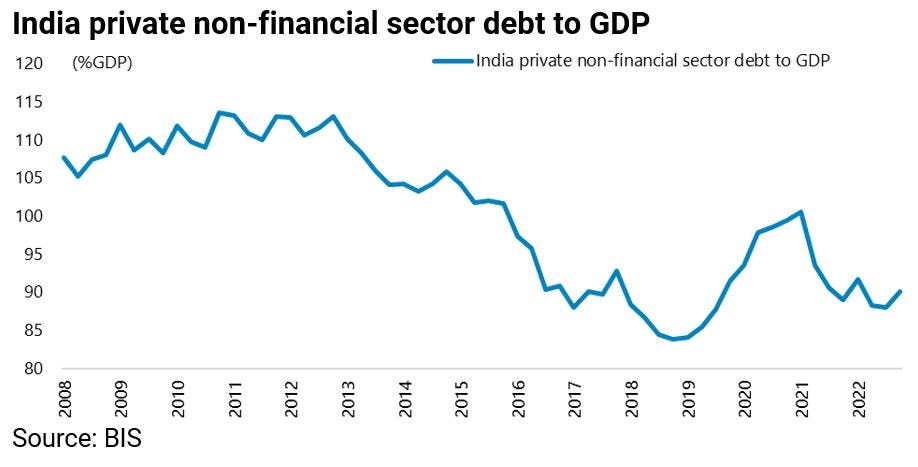

The other way of gauging the extent of the potential for a sustained capex cycle is the dramatic deleveraging of corporate balance sheets which has taken place in recent years.

The corporate debt to equity ratio for large listed companies is 0.6x, the lowest level since FY06.

Indeed India’s private sector has deleveraged in the past ten years, a period during which most of the rest of the world has seen private sectors increasing leverage to take advantage of the prevailing low interest rates.

Thus, India’s private non-financial sector debt as a percentage of GDP, including households and corporates, has declined by 24.4 percentage point from 113.1% at the end of 2012 to 90.1% at the end of 2022.

An excellent piece, as always!