Analysis of the Ongoing China-US Trade Talks

Author: Chris Wood

The recently concluded US trade deals with Japan and Europe, or perhaps it should be said reportedly agreed, are a reminder that China is the only country so far to have stood up to President Donald Trump in terms of the tariff negotiations and subsequent concessions by the US.

Thus, the Trump administration decided in mid-July to allow Nvidia to sell previously banned H20 GPU chips to China again.

In return China’s Ministry of Commerce has stated that it will expedite the review and approval of rare earth-related export license applications.

In this respect, Beijing has successfully linked the rare earth issue with US export controls of advanced semiconductors.

On this point, subsequent developments suggest that the US needs China’s rare earth resources just as much as China wants access to US advanced semiconductors.

As for the recent US trade deals with Japan and Europe, Japan reportedly negotiated a 15% “reciprocal” tariff last week, down from the threatened 25%, but only by agreeing significant other concessions, including investing US$550bn in the US, buying 100 Boeing aircraft, increasing imports of US rice by 75% and purchasing US$8bn in US agricultural and food products.

While Trump and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced on Sunday that the US and EU had agreed to the framework of a trade deal that included a 15% tariff on EU exports to America, compared with the threatened 30%.

But the White House stated that, as part of the deal, the EU will purchase US$750bn in US energy and make new investment of US$600bn in the US by 2028.

How enforceable all of the above is remains unclear.

Meanwhile, Beijing has continued to view the imposition of controls on the exports of tech products as the equivalent of a declaration of economic war against China since it has amounted to a deliberate effort to prevent the upgrading of the mainland economy.

Still this writer also remains of the view that these export controls in the semiconductor space are also against America’s own national interest.

This is not only because they have deprived many American tech companies of their biggest customer but also because they have created a massive incentive for China to develop the technology itself.

This is in addition to the reality, as previous discussed here, that an estimated 10% of Nvidia’s banned chips ended up in the mainland last year via the second-hand market (see The Current State of the US Economy – Lower Rates and AI Angst, 27 March 2025).

To his credit Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang made the same argument in a news conference in late May at the annual Computex conference in Taipei following his keynote speech delivered on 19 May.

His key point was that Nvidia has lost significant market share to Huawei in the mainland market as a result of the export controls and that the US should not underestimate Chinese competitors in this area (see Financial Times article: “Nvidia chief Jensen Huang condemns US chip curbs on China as ‘a failure’”, 21 May 2025).

Huang told reporters that Nvidia’s market share in China has declined from nearly 95% to 50% over the past four years.

The Nvidia boss also criticized in that same speech Washington’s decision to ban a Nvidia product designed specifically for the Chinese market which had turbocharged Chinese rivals, led by Huawei, to build competitive AI hardware.

He noted that the company "walked away from US$15bn of sales" in China as a result of the Trump administration’s recent ban on shipments of its H20 chips.

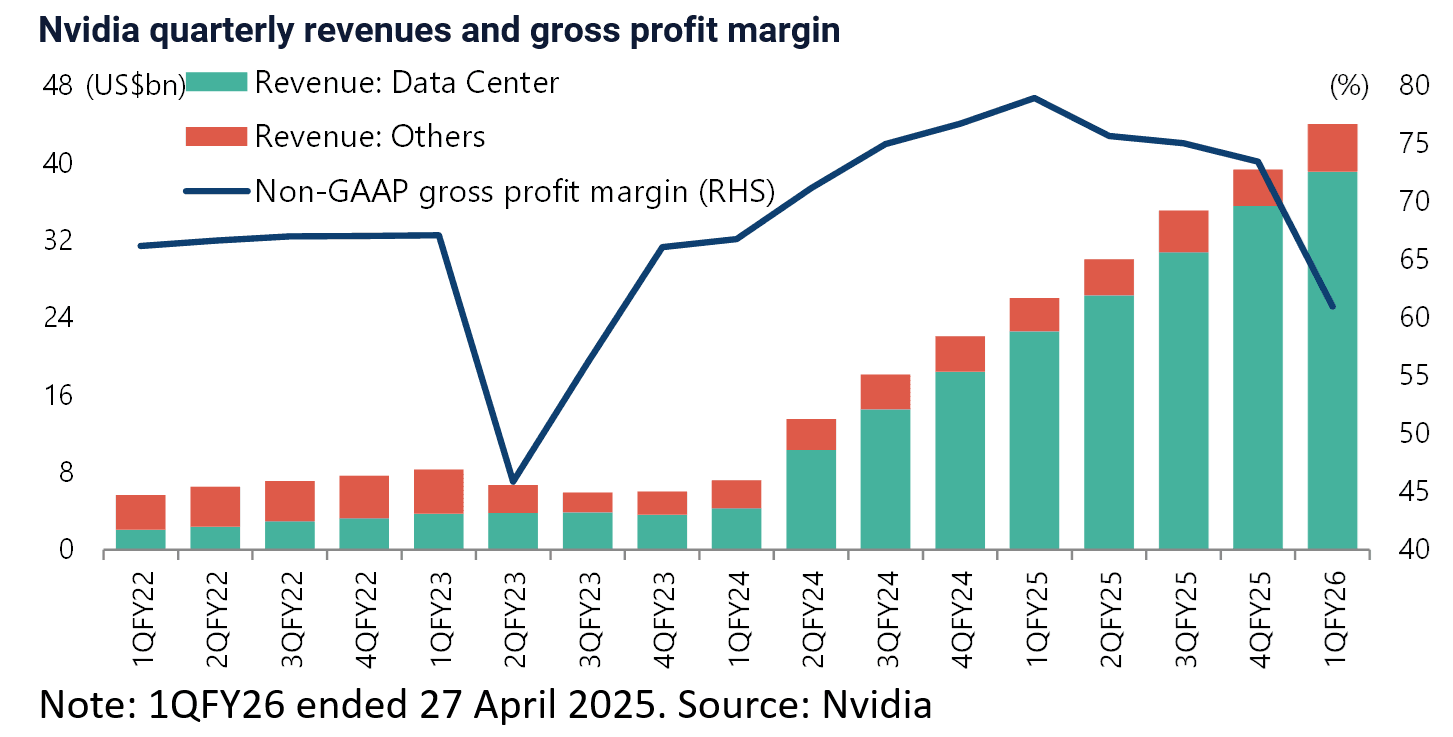

Nvidia reported in late May that it had written off US$4.5bn in inventory in the first quarter ended 27 April.

As a result, Nvidia’s GAAP and non-GAAP gross profit margins declined sharply to 60.5% and 61% respectively in the first quarter despite record revenue of US$44.1bn.

This writer assumes that the Nvidia boss has always been of this view since the export controls on the sale of advanced semiconductors were first announced in October 2022 during the Biden administration.

But it is interesting that he chose to go public with his criticism of the policy at this time, most particularly as he has the potential vulnerability in America’s politically charged environment of being ethnically Chinese having been born in Taiwan.

Still the Nvidia boss probably felt more comfortable going public after the US and UAE announced a week earlier a plan to build the largest campus of AI data centres outside America, which will be supported by Nvidia’s chips.

The 10 square mile AI campus in Abu Dhabi, with 5 gigawatts of power capacity for AI data centres, will be built by UAE state-backed firm G42 and operated in partnership with several US companies, according to the agreement announced on 15 May by the US Commerce Department.

The key part of this AI deal is that the Trump administration will allow UAE to import 500,000 advanced Nvidia chips each year mainly to support the campus development.

It should be noted that, just before Trump’s Middle-East trip in mid-May, the US Commerce Department rescinded the so-called “AI Diffusion rule” introduced by the Biden administration in January which was intended to come into effect on 15 May.

This aimed to limit exports of advanced AI chips and models to countries worldwide.

This rescinding enables the imports of AI chips into UAE and Saudi Arabia where a similar deal was also announced during Trump’s recent visit to the Middle East.

This new market is now called “sovereign AI”. Meanwhile, as already noted, Nvidia is now able to sell H20 chips into China again.

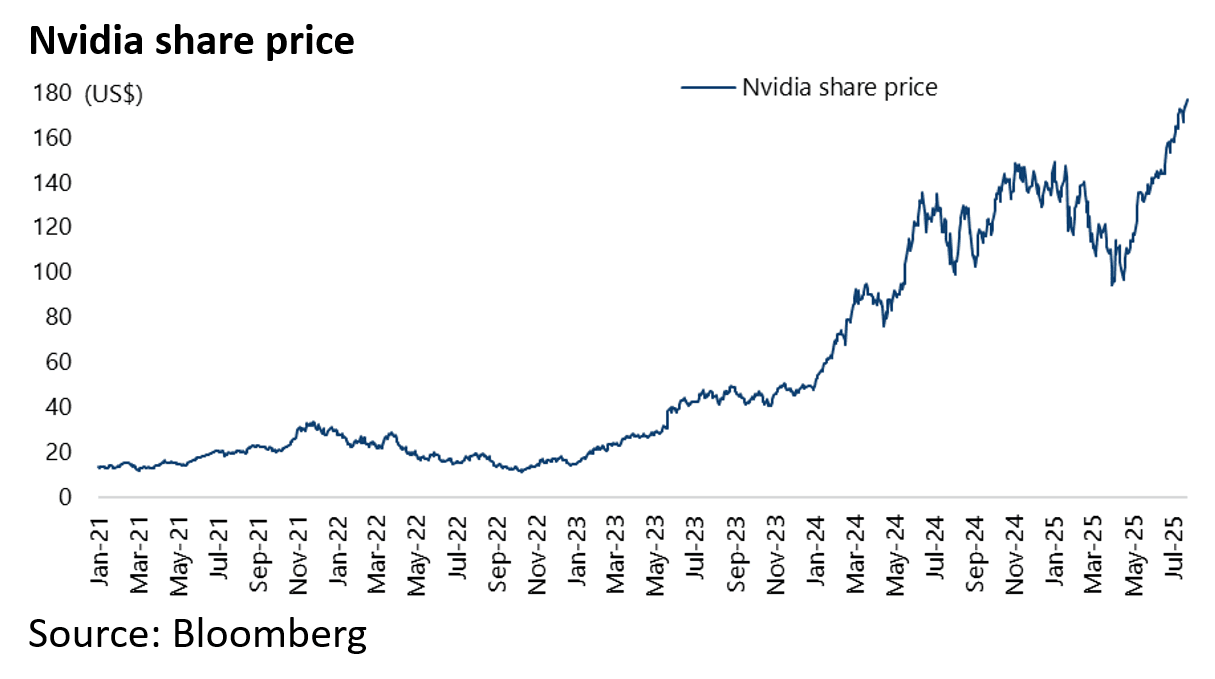

These developments help explain why the Nvidia share price has made new highs of late along with the continuing evidence of the hyperscalers continuing to engage in the AI capex arms race.

Our Analysis of the Ongoing China Trade Talks

Meanwhile, the obvious potential for a definitive trade deal between the US and China remains China offering to move production to America.

This would give Trump a “win” since he has always maintained that the goal of his tariff policies, aside from increasing tax revenues, was to create incentives for companies wanting access to the US consumer market to move production there.

Meanwhile, for China a CATL plant in America would turn a negative into a positive.

While the potential further removal of export controls in the tech area would allow China to start buying US tech products again in an unconstrained fashion.

Clearly, such a policy U-turn would be opposed by Washington’s national security lobby.

But Trump is not by nature a national security hawk; though clearly recent history shows that he can be influenced by them.

Still the rare earth issue must be a shocking reminder to the same national security establishment of the US’s lack of leverage over China.

The issue remains that it is unrealistic for Washington to assume that China is going to ease up controls on rare earths if the US does not do the same as regards exports of US tech products.

This is now seemingly better understood.

China's Stance on the Yuan

The other interesting point is whether the issue of the exchange rate has been raised in recent meetings between the US and China in Geneva in May and London in June as regards the trade negotiations, and now in Sweden this week.

The official line is that it has not been discussed.

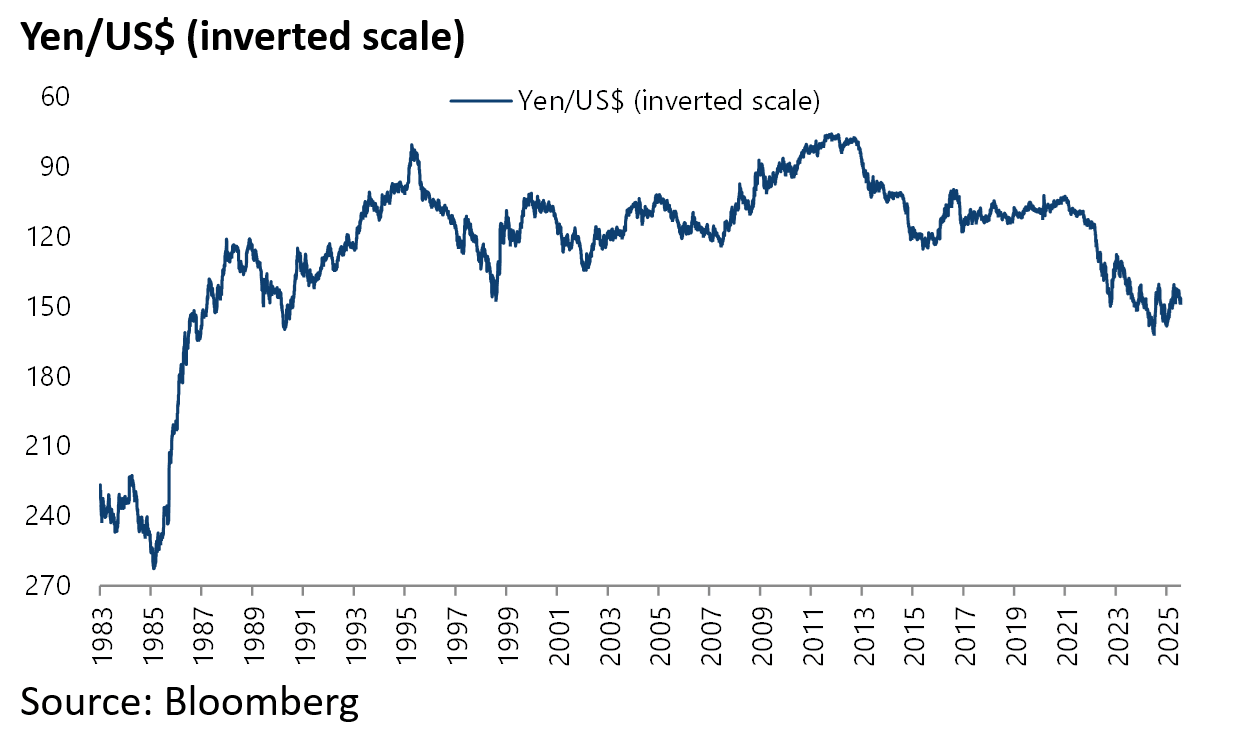

Still, it is conceivable, for example, that the US may have asked for China to float the currency. Such an approach would seem unlikely in the extreme to this writer, not least because Beijing knows that the post Plaza Accord-triggered yen appreciation laid the groundwork for Japan’s Bubble Economy.

The yen appreciated from Y262/US$ at the time of the Plaza Accord in 1985 to Y121/US$ by the end of 1987.

But a stated willingness of Beijing to allow a gradual strengthening of the currency would seem achievable.

First, the direction of travel is for the Chinese currency to appreciate anyway, in line with other Asian currencies as previously discussed here (see Why The Time Has Come to Overweight International Stocks, 19 June 2025).

Second, it is what is required to promote the desired increase in consumption as a driver of China’s economy.

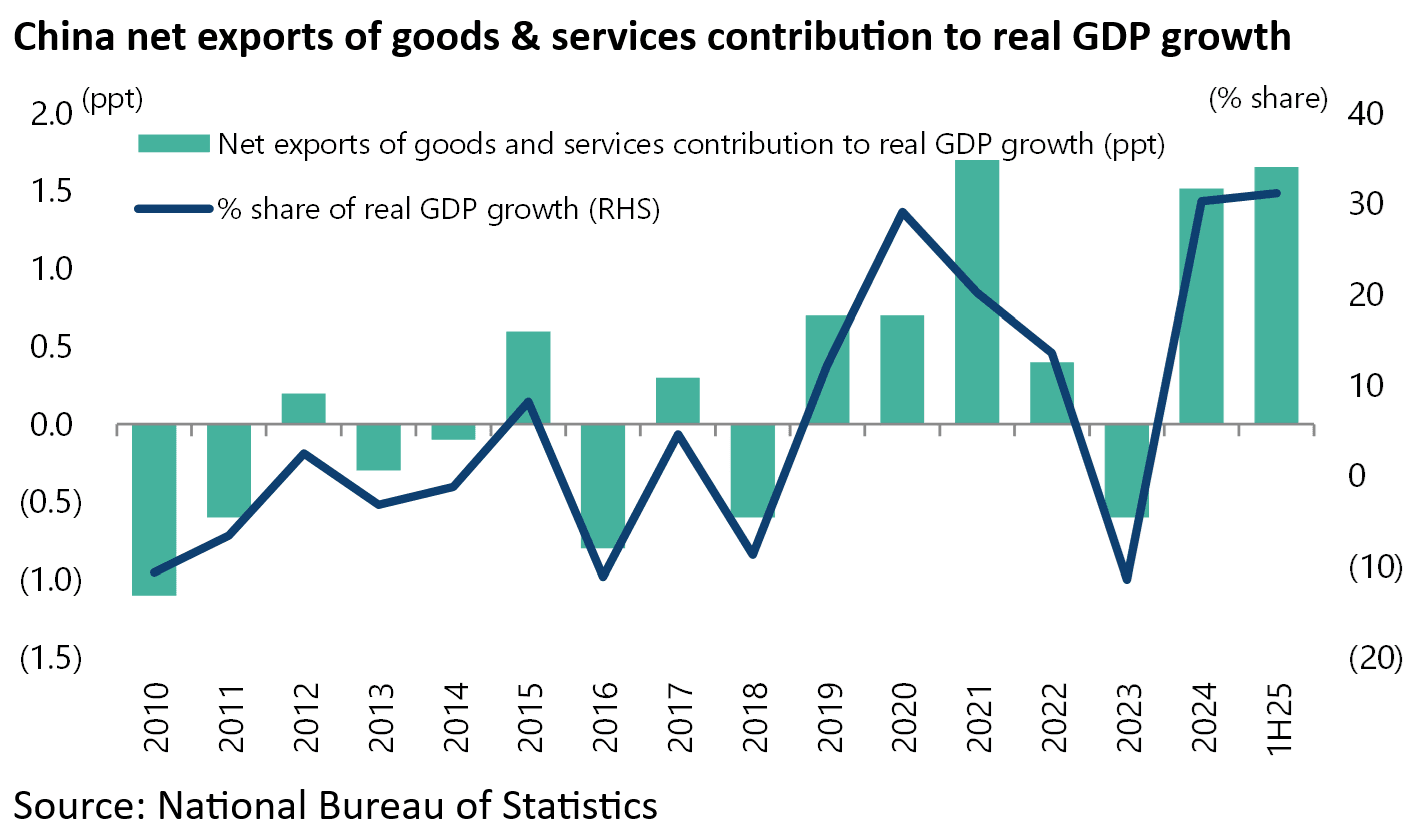

Remember that in the post-Covid years net exports have again picked up as the main driver of China’s real GDP growth, as also discussed here previously (see US or China – Who has the Stronger Negotiating Position in Trade Talks?, 16 June 2025).

Thus, net exports contributed 1.65 percentage points to real GDP growth of 5.3% YoY in 1H25 and 1.5ppts to 5.0% growth in 2024, accounting for 31.2% of the 1H25 growth and 30.3% in 2024.