A Roadmap for Investing in 2023 and 2024

Author: Chris Wood

As concerns over US regional banks continue to percolate, it is worth noting that the most interesting point about Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), and the one missed predictably by most mainstream media at the time of its failure in mid-March, is the hint it provides of the growing, mostly unacknowledged, financial problems building in the former boom areas of private equity and private lending.

This is because SVB was unusual as a bank because it was so closely intertwined with the private equity ecosystem.

Indeed this writer heard one observer describe it as the equivalent of a “highly levered PE fund”.

As discussed here previously (When will the recession start? The answer may surprise you, 3 May 2023), the fact that the credit boom in the past cycle was in the private lending, or shadow financing, area will mean that the lags in monetary policy will prove to be even longer than usual.

But that does not mean that there will be no impact from monetary tightening.

Rather in a world where the US enters recession, SVB will be seen as the first hint of the problems to come in private equity, just as the failure of New Century Financial back in April 2007 was the first hint of the problems to come in subprime mortgages in 2008.

In this respect, the presumed road map is as follows.

2022 was the year when US equities suffered multiple contraction from monetary tightening.

This year will be the year when earnings downgrades hit the stock market if the US recession forecast proves to be accurate.

This is now the key issue in world financial markets.

Then 2024 will be the year when markets will have to deal with the emerging credit problems in the private space.

In this respect it is amazing that the leverage loan price index is still trading only 5.7% below its recent high reached in January 2022 and seemingly only 7.2% below the all-time high reached in March 2005.

Stubborn Inflation May be Tying The Fed's Hands on Monetary Easing

With the banking problems likely to lead to tighter credit, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell now finds himself in a bit of a pickle given his continuing wannabe Volcker act, which saw the Fed raise rates by another 25bp last week to 5.0-5.25%.

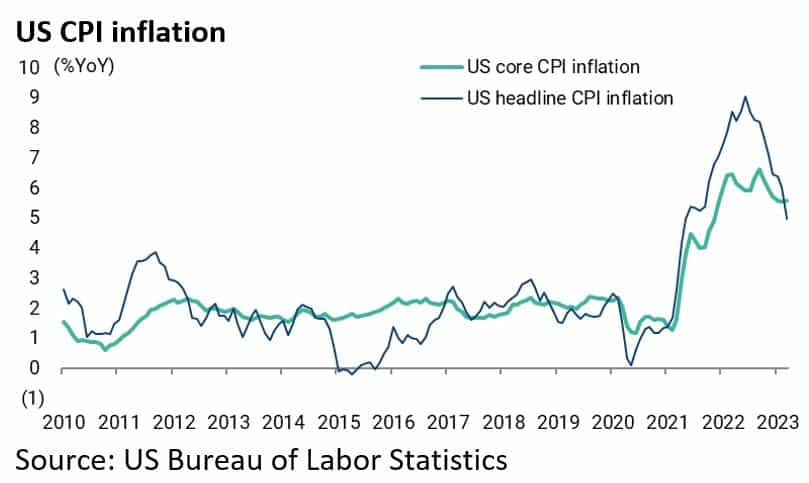

The last CPI data contained mixed signals.

Headline CPI inflation slowed from 6.0% YoY in February to 5.0% YoY in March, compared with consensus expectations of 5.1% YoY.

While core CPI inflation rose from 5.5% YoY in February to 5.6% YoY in March, in line with consensus expectations.

It is worth noting that the decline in headline CPI inflation was primarily driven by a 6.4% YoY decline in energy prices as a consequence of the base effect.

Excluding energy, headline CPI inflation slowed only from 6.1% YoY in February to 6.0% YoY in March.

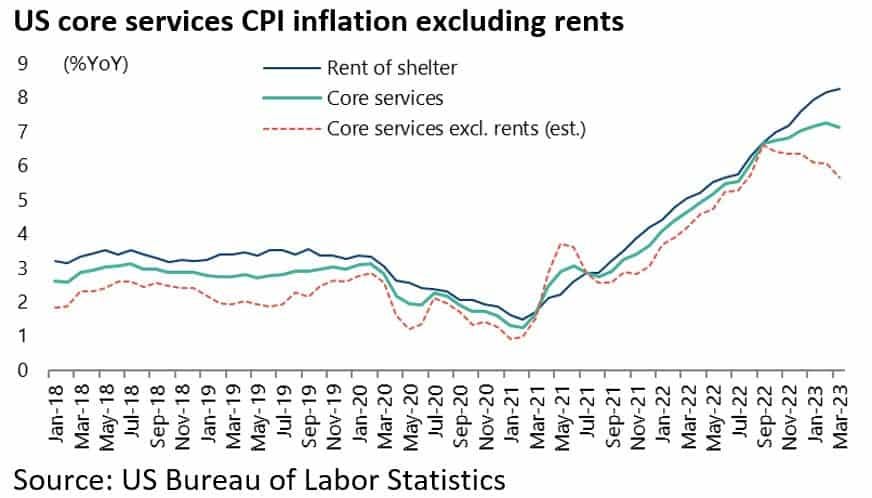

Still the problem for the Fed is that core services inflation slowed only from a 40-year high of 7.3% YoY in February to 7.1% YoY in March, with shelter CPI rising from 8.1% YoY in February to 8.2% YoY in March.

It is further worth highlighting that the Cleveland Fed’s median CPI inflation rose to 7.20% YoY in February, the highest level since the data series began in December 1983, and was still 7.08% YoY in March.

A Look at the State of Play With Bank Deposit Outflows

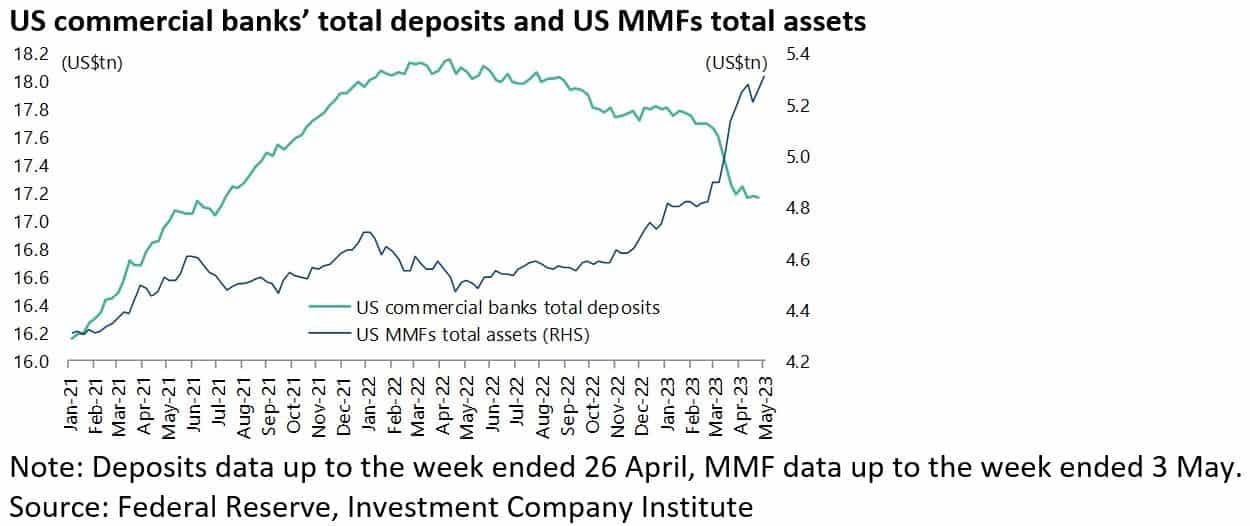

Meanwhile, as regards the presumed looming tightening of credit standards, the state of play on outflows out of US bank deposits and inflows into US money market funds is as follows.

US commercial banks’ deposits have declined by US$991bn or 5.5% since peaking in April 2022, while small regional banks’ deposits have declined by US$259bn or 4.6% since peaking in early December.

As for US money market funds’ assets, they have increased by US$841bn or 18.8% since April 2022.

Bailout of SVB Yet Another Bailout of the Rich Over Everyone Else

It is worth noting the extraordinary, though not unfortunately particularly surprising, decision by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) in March to extend the guarantee of deposits to all depositors in SVB to the full amount and not only to those up to US$250,000, which is meant to be the FDIC insurance limit.

This has provided the latest example of Uncle Sam bailing out rich people, an approach adopted during the 2008 financial crisis which triggered lingering resentment on the entirely legitimate view that the empirical evidence proved that there was one rule for Main Street and another for Wall Street.

This maxim can now be extended to Silicon Valley.

The justification of this extraordinary move is that 96% of SVB’s deposits were uninsured (i.e., above the US$250,000 limit or in foreign offices).

Still the moral hazard is enormous.

The other extraordinary move was for the Fed to set up on 12 March a new “bank term funding program” (BTFP) where collateral will be valued at par, or 100 cents on the dollar, as opposed to the mark to market value of those securities.

This move has been designed to ease concerns, first triggered by SVB, about the value of “assets held to maturity” on banks’ balance sheets, which accounted for an average 42% of US large-cap banks’ total securities holdings and 34% of mid-cap banks’ as at the end of 2022.

Banks are now borrowing US$75.8bn from the programme as of 3 May, down from US$81.3bn on 26 April which was the highest level since the vehicle was set up.