A Recession is on the Way, But When it Starts Will Surprise You

Author: Chris Wood

Monetary tightening expectations in the US have ratcheted up again, with the terminal rate now at 5.09% against the current Fed funds effective rate of 4.83%, implying a further 25bp rate hike at the next FOMC meeting on 3 May.

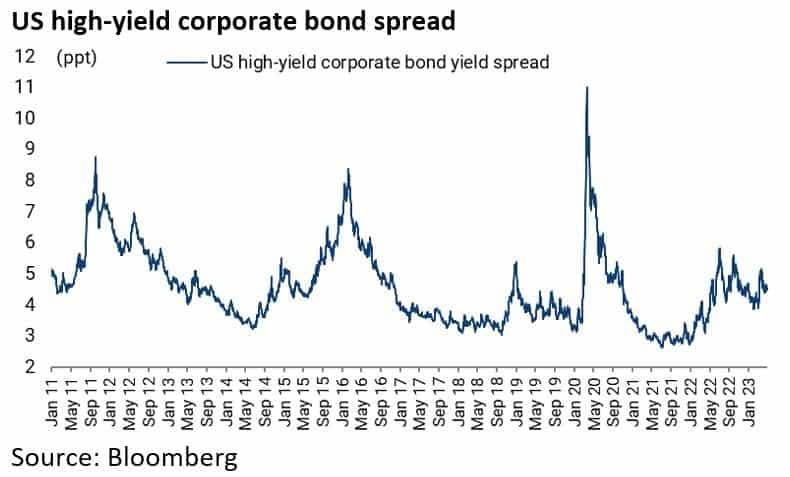

The Fed has, despite recent bank sector scares, continued to draw comfort from relatively benign “financial conditions” in the US, a definition which boils down primarily to credit spreads.

Thus, the continuing relative calm in the corporate bond market is in significant part explained by the “terming out” of debt, as previously discussed here (see Canary, Meet Leveraged Loans, 29 March 2023).

The US high-yield corporate bond spread has declined from a recent high of 583bp in July 2022 to 452bp.

While the Chicago Fed’s National Financial Conditions Index has fallen from -0.106 in October to -0.302 in the week ended 21 April, though up from -0.574 in January 2022.

Still the risk for the Fed is that it is once again fighting the last war since its failure to pay more attention to credit spreads, and the related issue of what was going on in the asset-backed securitisation markets, was a key reason why former Fed chairman Ben Bernanke and his then comrades in arms were so totally unprepared for the subprime mortgage crisis back in 2007 and 2008.

This time around the problem for the Fed is that the normal lags in the impact of monetary policy will, in this writer’s view, be even greater than in the past because the credit boom in this cycle has been in the private lending market, the dynamics of which are much less understood by central bankers, macro-economists and investors at large.

This is because there has never been a cycle, so far as this writer is aware, where private lending has driven high beta credit growth to a far greater extent than credit extended by the commercial banks.

Private Credit is Extending the Typical Interest Rate Hike Adjustment Period

The other key point, as also discussed here previously (Small Business, Not the Bond Market, Will Cause the Next Recession, 28 April 2023), is that everybody involved in the world of private equity has an incentive to delay price discovery for as long as possible, which means that the impact of monetary tightening will be even more delayed than normal amidst continued seemingly benign “financial conditions”.

But remember that the leveraged loans used to fund private equity deals are geared to rising floating rates and the word is that the vast majority of borrowers have not hedged against interest rate risk.

From a bigger picture macro perspective, the even longer lags in monetary policy in this cycle create a bigger risk of an even more pronounced “bull trap” stock market rally than normal as investors become convinced that the economic downturn can be avoided.

And all bear markets are characterised by such bull traps.

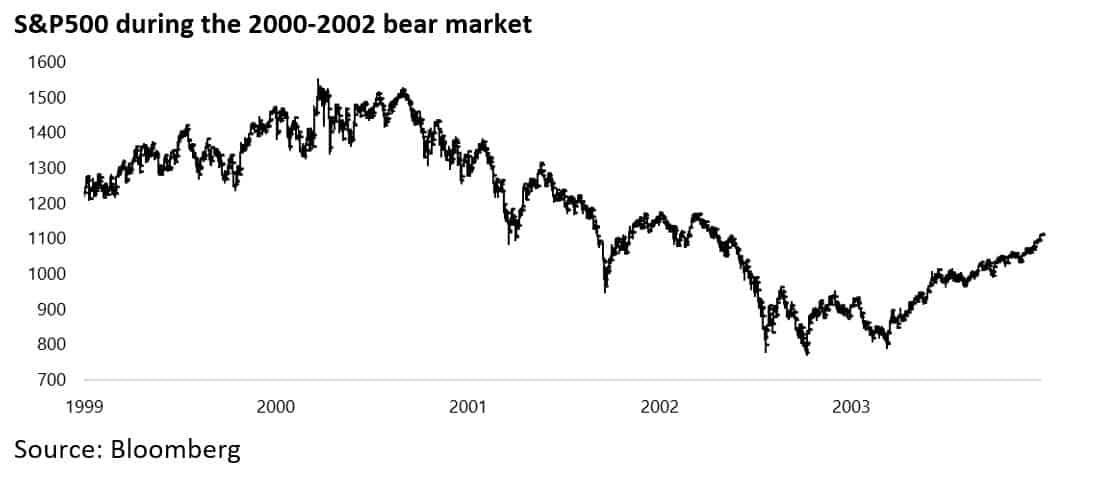

One good example of this was the bear market in 2000-2002, which followed the burst of the dotcom bubble in March 2000.

The S&P500 declined by 51% from the then peak in March 2000 to the bear market bottom in October 2002.

But the S&P500 rallied by 22% from 22 March 2001 to 22 May 2001 and by 25% from 21 September 2001 to 7 January 2002.

So far the rally in the S&P500 from the October 2022 low has been “only” 19%.

Presidential Cycle Could Drive more Market Upside for Now

The other argument for more of a countertrend rally is the US stock market’s impressive historic track record in the third year of the presidential cycle.

Thus, in a typical pre-election year the Dow has since 1935 risen an average 46% off the mid-term year low (i.e. this time October 2022)

For the current cycle, the Dow has only risen so far by 19% from its 2022 low.

This is certainly a track record which commands a certain respect and would make this writer nervous of shorting the market on a leveraged basis, most particularly with the growing prospect for a change in Fed language.

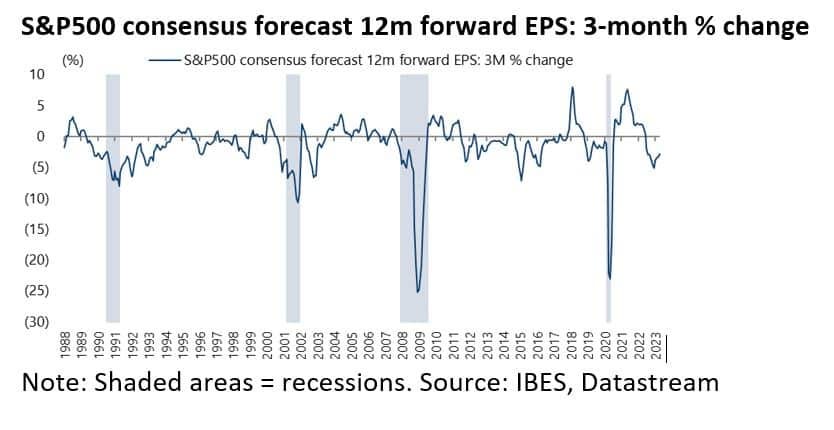

Still, as regards the trend in US earnings there is clearly room for more downgrades if there is a US recession later this year, and this has now become the key issue for financial markets.

Corporate Profit Decline Not Yet at Recessionary Levels

The current state of play on the US profit trend is as follows. S&P500 companies’ annualised as reported earnings have risen by 84% since 4Q20 as of 4Q22, though they have declined by 12.7% since 1Q22, while the macro measure of non-financial corporate profits after tax is up only 40% since 4Q20.

Meanwhile, S&P500 consensus forecast 12-month forward earnings have been downgraded by 2.8% over the past three months, following a 5.1% downgrade in the three months to December.

By way of comparison, the average peak earnings downgrade over a three-month period has been 17% in the last four recessions in America.