A Mar-A-Lago Accord Deep Dive: Implications and Risks for America

Author: Chris Wood

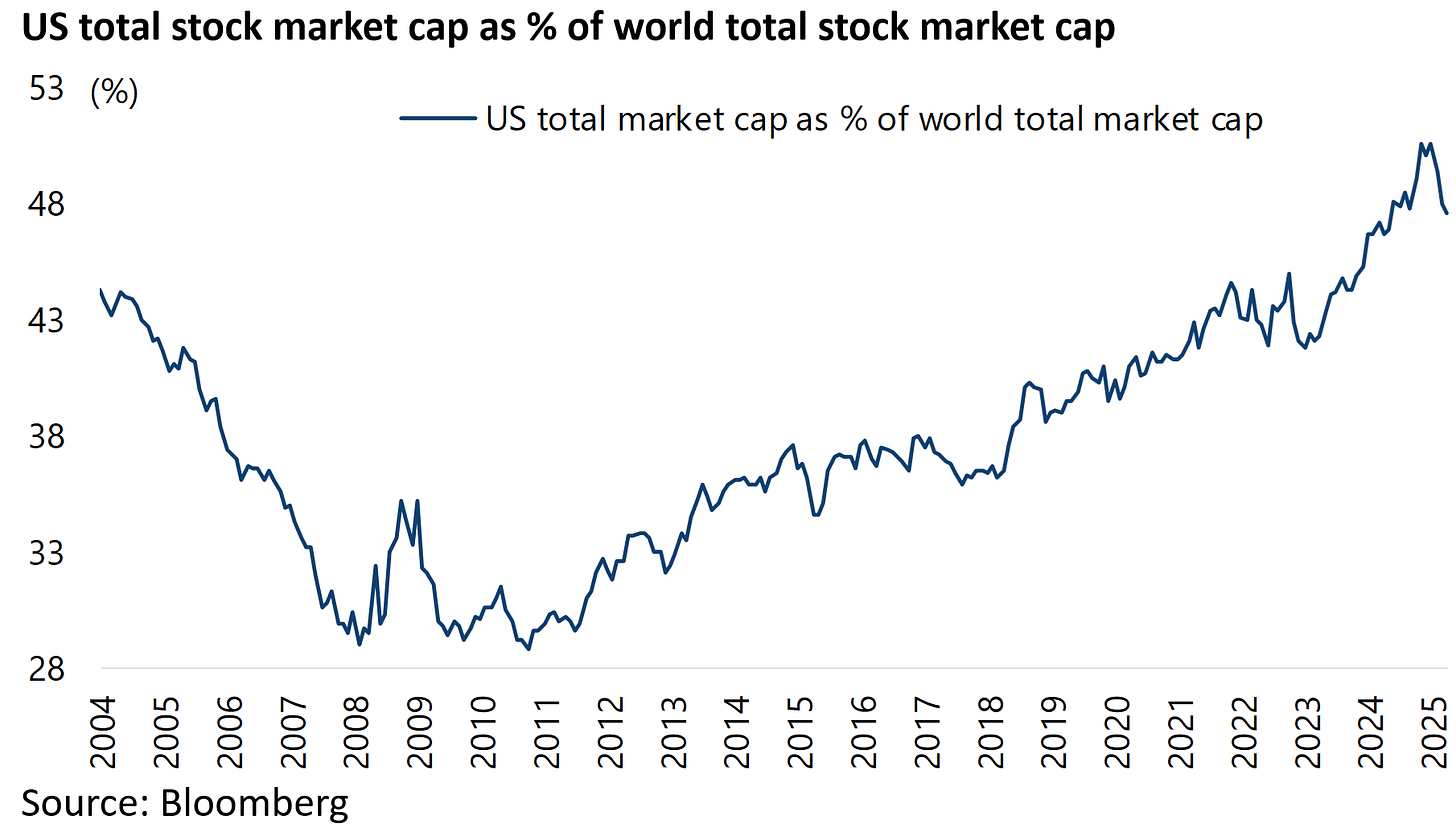

The base case here remains that US stock market capitalisation, relative to world stock market capitalisation, made an all-time peak at the end of last year amidst the then prevailing talk of “American exceptionalism”.

That means global investors should be looking to sell rallies in the US and buy corrections in Europe, China and India where there is the most evidence of improving fundamentals.

That requires a US rally of the kind seen in recent days as investors hope that Donald Trump delivers a U-turn on his tariff agenda.

Thus, the US equity rebound since 22 April is the direct result of Donald Trump’s seeming U-turn on his stance on China tariffs.

The uncertainty triggered by the 90-day reprieve on tariffs announced on 9 April has clearly been causing widespread deferment of decision making on the part of corporates, as is evident from companies’ guidance when they report first quarter results.

Still, Trump is now seemingly wavering on that 90-day pause he announced just two weeks ago.

In a press conference on 23 April, Trump said he would impose tariffs on countries in two to three weeks if trade deals were not reached.

Understanding the Meaning of the Mar-a-Lago Accord

Meanwhile, this writer has been looking in more detail at the theoretical underpinnings behind the proposed Mar-a-Lago Accord which were discussed in a 41-page report written by Stephen Miran last November (see Hudson Bay Capital report: “A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System” by Stephen Miran, November 2024).

It should be noted that Miran is now Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers.

It is clear that what is being envisaged is more than just appreciation of East Asia currencies.

This was the prime achievement of the 1985 Plaza Accord which is widely viewed as the precedent for the envisaged Mar-a-Lago accord.

Perhaps the most unorthodox and, in this writer’s view, controversial idea of the Miran paper, is that other nations will be “encouraged” to swap holdings of dollars, short-term Treasuries or even gold for long-term or perpetual dollar bonds suitable for repurchase deals at the Fed.

The idea is that such an arrangement would be some form of quid pro quo for countries to enjoy the protection of America’s “security umbrella”.

Miran poses the rhetorical question how the US can get trading and what he calls “security partners” to agree to such a deal.

He cites three reasons.

First, there is the “stick” of tariffs. Miran writes that “it is easier to imagine” that after a series of punitive tariffs, trading partners like Europe and China will become “more receptive” to some manner of currency accord in exchange for a reduction in tariffs.

Second, there is the “carrot” of the defence umbrella and the risk of losing it.

Third, he says there are “ample” central bank tools available to help provide liquidity in the event of interest rate risk.

This relates to the issue of countries being asked to agree to hold long-term US government debt in what is described in the Miran paper as a “duration agreement”.

Thus, the concept of “special century bonds” is floated.

Such an arrangement will, as Miran notes, “shift interest rate risk from the US taxpayer to foreign taxpayers”.

Still, he argues that the mark-to-market risk of holding such longer-term debt, from the standpoint of foreign governments, can be “mitigated” via swap lines whereby the Fed or the Treasury’s Exchange Stabilization Fund can lend dollars to reserve holders at the par value (i.e. the cost) of their long-term debt holdings rather than at the market value.

This is described as a “perk” of being inside such a Mar-a-Lago Accord.

Such an approach is considered necessary given the risk of holding long-term Treasury debt for foreigners is clearly much greater today given that America’s fiscal situation has deteriorated significantly since 1985 at the time of the Plaza Accord.

Indeed, gross US government debt as a percentage of GDP is now in excess of 120%, compared with only 40% back then.

Still, it has to be wondered why most foreign countries would agree to such a deal, even if the swap idea involves a clever financial engineering expedient.

Indeed, it is compared in the Miran paper to the “solution” the Fed came up with in the aftermath of the Silicon Valley Bank blow-up in March 2023, namely the so-called “Bank Term Funding Program” where the Fed lent to regional banks against the par value of their bond holdings rather than the market value.

Such an approach is clearly a fudge, not a fix.

Meanwhile, it also has to be wondered if the US has the bargaining power over trading partners the Trump administration seems to think it has, given the extreme nature of its net international investment position (IIP) which means America is massively dependent on foreign capital.

Thus, America’s net IIP deficit has risen from US$7.8tn or 39.9% of GDP at the end of 2017 to a record US$26.2tn or 89.9% of GDP at the end of 2024.

True, access to the American consumer market is very important, but it is also the case that developing countries, led by China, have in recent years been sensibly focused on reducing their dependence on the US, as reflected in the surge in trade between the emerging markets.

Thus, emerging markets’ exports to emerging markets rose to an annualised US$4.875tn in the 12 months to December 2024, accounting for 46.8% of total emerging markets’ exports, up from US$292bn, or 23.2% of total emerging markets’ exports in 1999, based on the IMF’s Direction of Trade Statistics.

How Valuable is the US Security Umbrella Really?

As for the so-called security umbrella, that clearly looks less reassuring to the Europeans based on Donald Trump’s stance on Ukraine.

Meanwhile, many countries in Asia will not view China as the security threat which Miran clearly believes it to be.

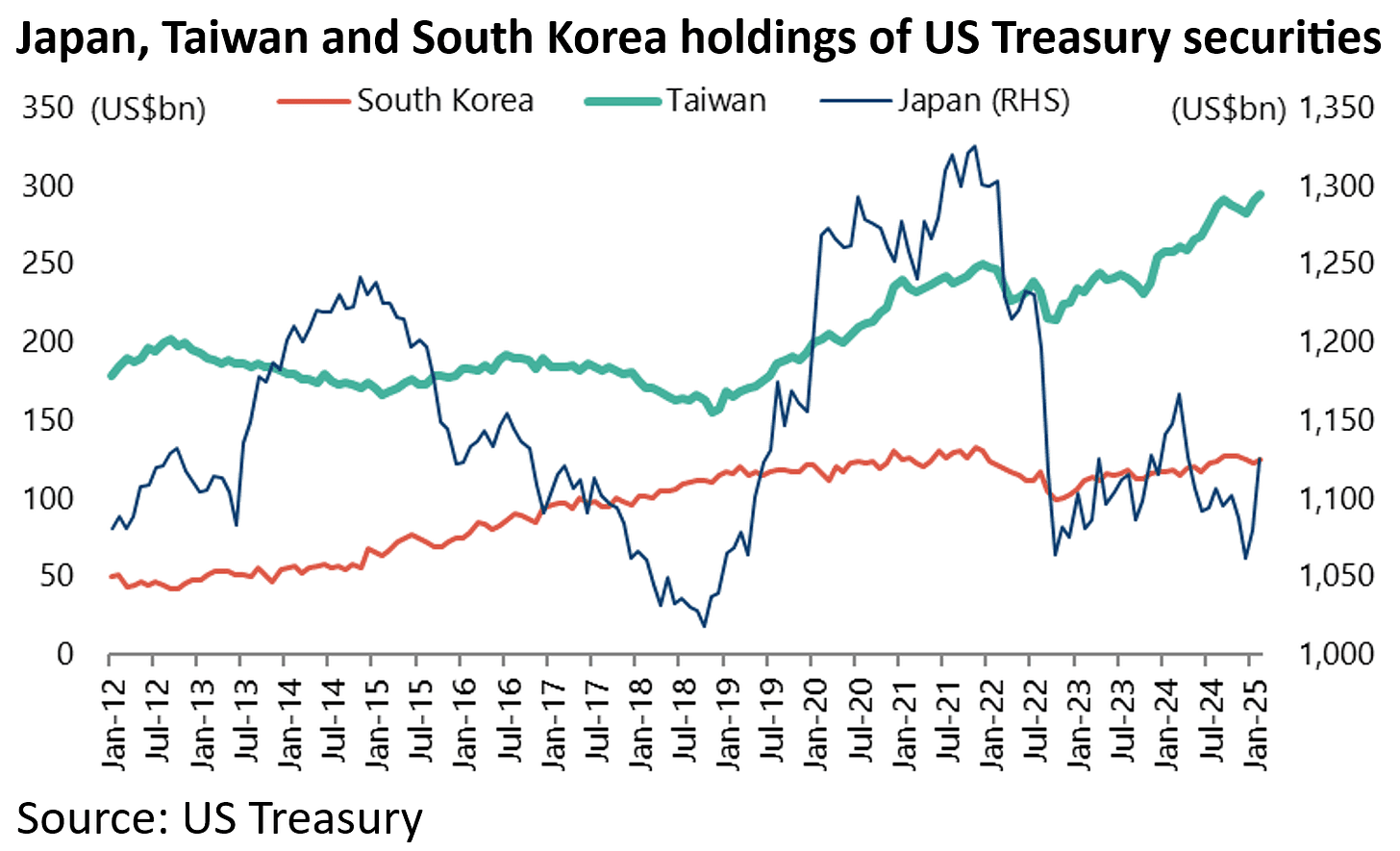

That leads this writer to the view that the countries most likely to accede to the sort of arrangement proposed by Miran are Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, all of whom have more grounds to view China as a security threat.

Fortunately, these countries are all significant holders of US Treasury debt, with Japan by far the largest.

Japan, Taiwan and South Korea held US$1.126tn, US$295bn and US$125bn worth of US Treasury securities as at the end of February.

Yet Another Reason Not to Own Long Term Treasury Bonds

There is also another issue to be aware of which, to be fair, is raised by Miran.

That is that a large share of foreign holdings of Treasuries is owned by private sector entities rather than central bank official holdings.

As he notes, such private sector players will not want to term out their holdings of Treasury bonds as part of some sort of accord, and that a resulting “run” out of Treasuries by such investors has the potential to “overwhelm the bid for duration” from the foreign official sector.

Foreign official holdings of Treasuries totaled US$3.90tn or 44.2% of total foreign holdings as at the end of February, compared with US$4.92tn or 55.8% of the total held by the private sector.

The above is indeed a risk and yet another reason to this writer not to own long-term Treasury bonds.

Should You Run From the Dollar?

Indeed, the Miran paper, and its potential policy implications, coupled with the reality of America’s net international investment position, are a reason to exit the dollar altogether.

In this respect, the risk is that America could get more than it wished for out of the proposed Mar-a-Lago Accord.

That is a collapse in the US dollar rather than the desired weakening.

On this point, the US dollar index has declined by 9% since Donald Trump entered the White House for a second time on 20 January.