A Catchup on Japan: Will Outperformance vs America Continue?

Author: Chris Wood

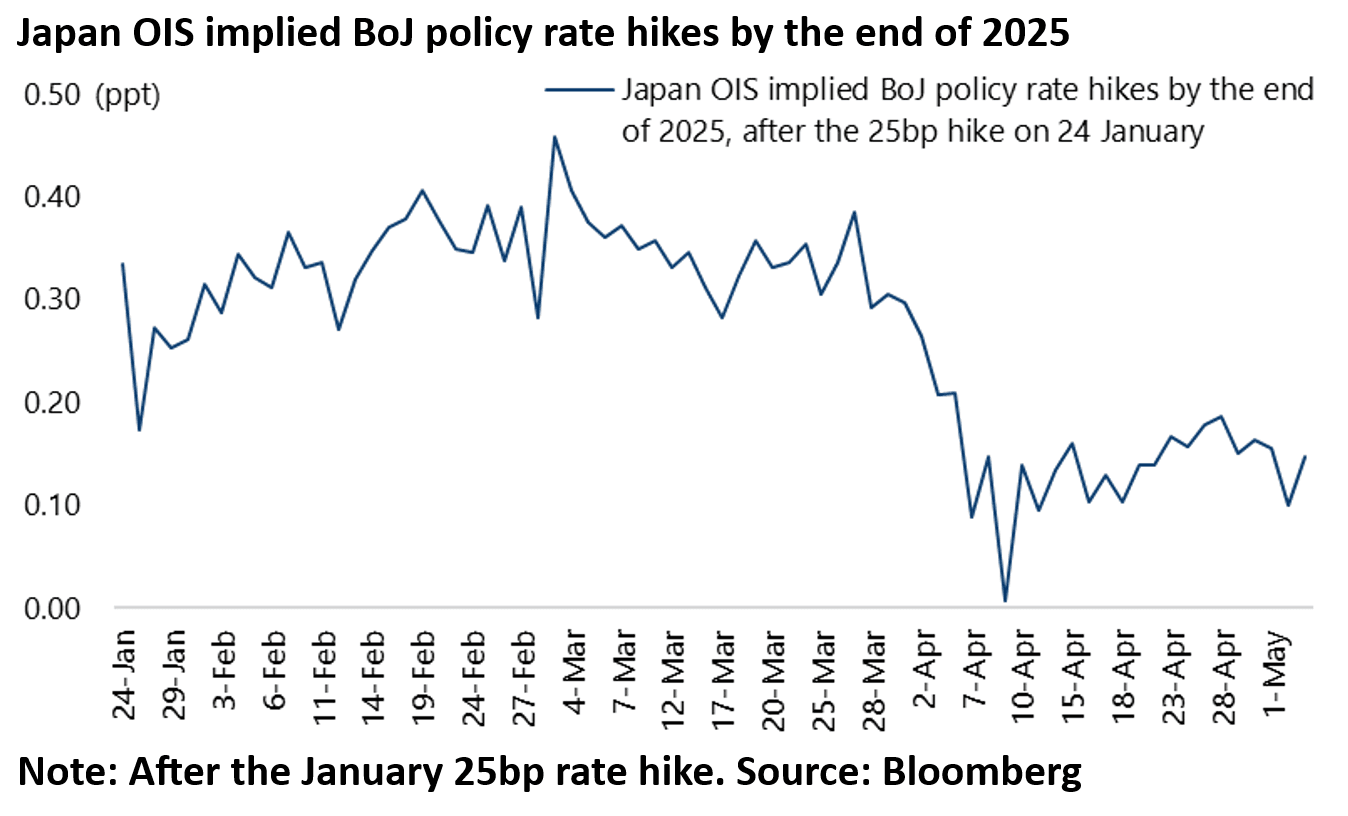

Money markets are still looking for another rate hike in Japan, but rate hike expectations have declined significantly of late given the growing fears of a US downturn.

While money markets are still expecting another 15bp of BoJ rate hikes this year, this is down from 46bp as recently as early March.

Indeed there is a real possibility that the BoJ has tightened for the last time in this cycle.

This risk will grow if the Fed starts easing by June as is the base case of this writer. Fed funds futures are now discounting 81bp of rate cuts by the end of 2025.

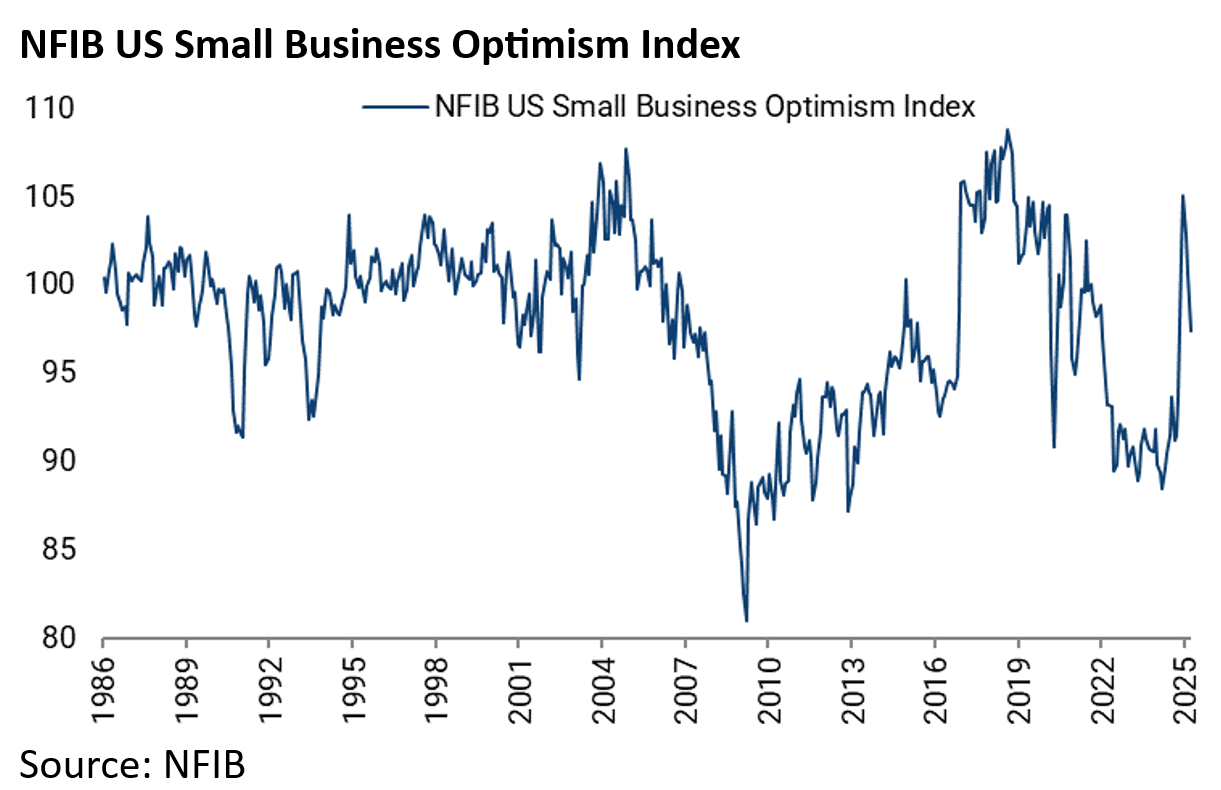

The ultra-cautious BoJ governor Kazuo Ueda was given the confidence to resume tightening by the election of Donald Trump last November and the resulting surge in cyclical optimism on the US economy highlighted by the spike in the US small business confidence index.

The concern is that the BoJ will once again prove a contrarian indicator.

The Japanese central bank is still haunted by two episodes of premature tightening which were then undermined by bouts of risk aversion originating from the US.

The first was in August 2000 ahead of the dotcom bust.

The second was in March 2006 when the BoJ ended quantitative easing ahead of the US subprime crisis.

The BoJ failed to cut at its meeting last week while it also halved the projected growth target for this fiscal year.

The BoJ policy board members lowered last week their real GDP growth forecast for this fiscal year beginning 1 April from 1.1% in January to only 0.5%.

How Resilient is Japanese Wage Growth?

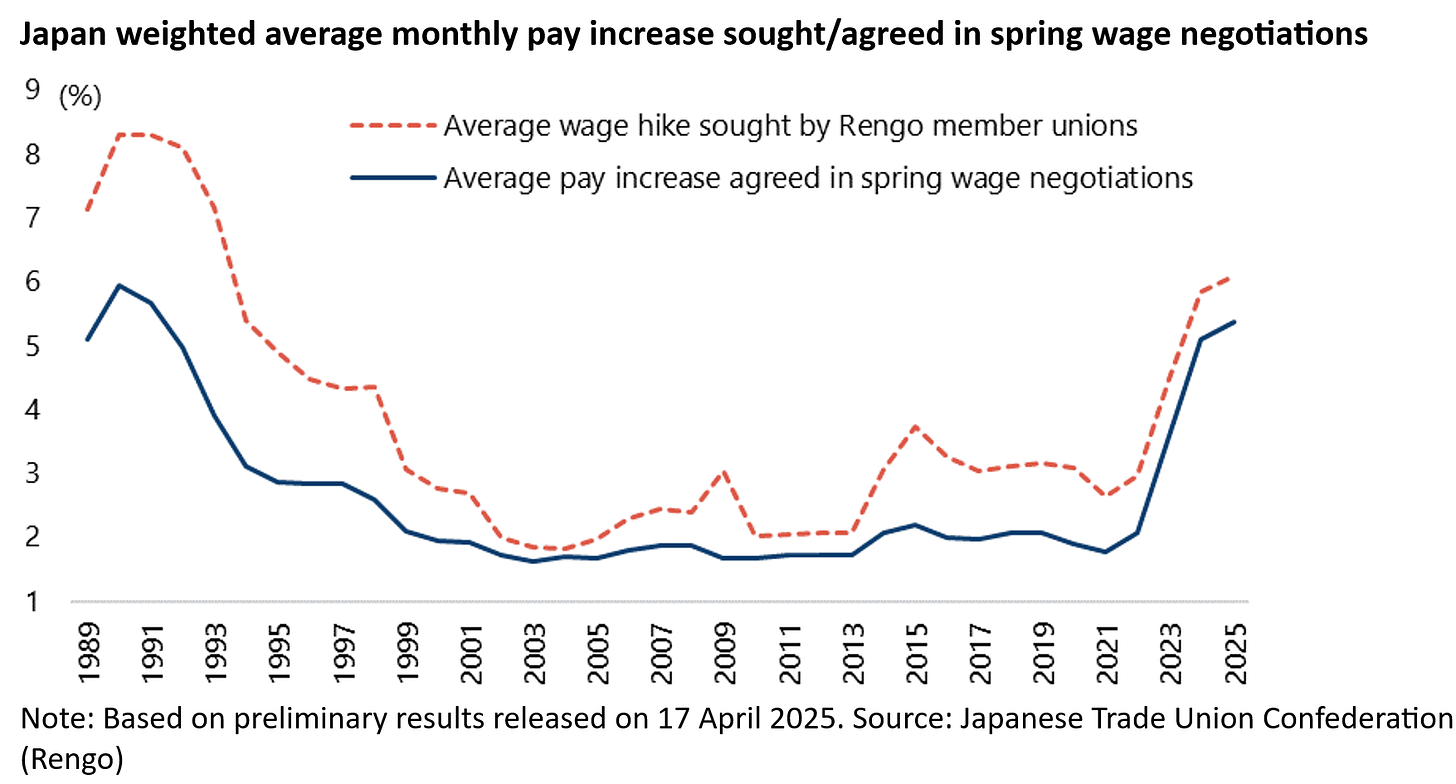

The increased confidence in the ability to achieve normalisation of monetary policy at the start of this year has been driven in part by the continuing evidence of rising wages.

Average monthly scheduled cash earnings per full-time employee rose by 2.8% YoY in December, the highest growth since the data series began in 1994, and was up 2.1% YoY in February.

While unions asked for a 6.09% wage increase in this year’s Shunto spring wage round, the highest pay hike sought since 1993.

The actual increase agreed so far is 5.37%, the largest increase since 1991, based on the preliminary results covering 3,115 affiliated unions reported by the Japanese Trade Union Confederation (Rengo) on 17 April.

The final result will only be available in early July.

The confidence in the resilience of wage growth is driven in large part by the growing reality of Japan’s demographically-driven labour shortage given the surge in the past 12 years in the female participation in the workforce as well as in the increase in the number of people employed in the 70-80 year old age group.

The female labour force participation rate has risen from 48.2% in 2012 to 55.6% in 2024, with female working-age participation rising from 63.4% to 76.1% over the same period.

While the total participation rate for people aged 70 or above is up from 13.3% in 2013 to 18.9% in 2024.

Labour Shortages are Driving High Wages for New Workers, The Opposite of in the US

The labour shortage issue is the subject of an interesting analysis on the elasticity of labour substitution in the latest BoJ outlook published in late January (see Bank of Japan report: “Outlook for Economic Activity and Prices”, 27 January 2025).

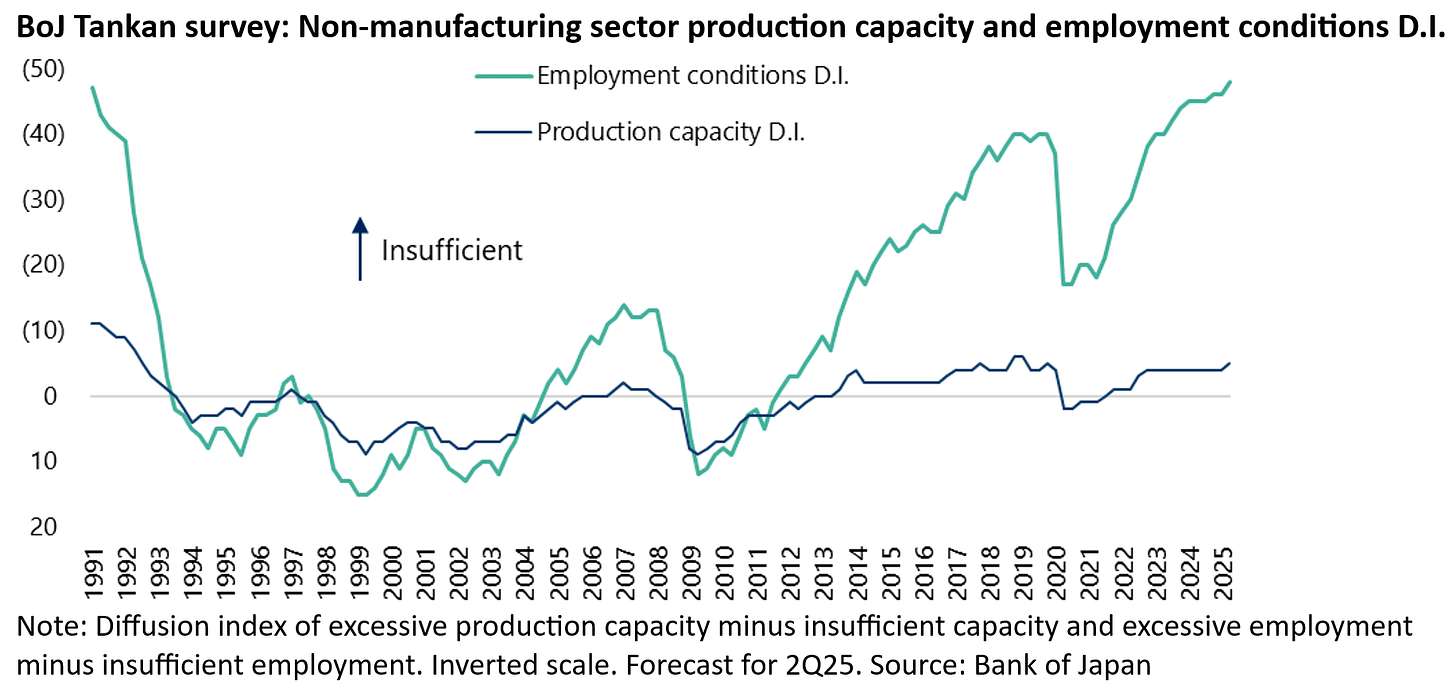

The report found that the services and construction sectors, in particular, are facing serious labour shortages and are suffering from labour supply constraints as the elasticity of substitution between capital and labour is low and it is difficult to substitute capital for workers.

And even in the manufacturing sector, the production capacity diffusion index (DI) has not indicated capital shortages in recent years, compared with the intensifying labour shortages indicated by the employment conditions DI.

This suggests that the sector is likely facing labour supply constraints.

For such reasons it has been pointed out to this writer that the labour shortage is one reason why the quarterly Tankan survey of corporate sentiment has in recent years projected a higher level of investment than the capex actually realised by corporate Japan.

Thus, the national accounts data shows that nominal private non-residential investment rose by 3.5% in FY23 ended 31 March 2024, while the Tankan survey showed a planned capex growth of 12.6% for FY23 in December 2023.

Similarly, nominal private non-residential investment increased by 5.3% YoY in the first three quarters of FY24 ended 31 December 2024, while the December Tankan survey shows a planned capex growth of 10% YoY.

The above is best explained by the lack of construction workers.

The average age of a construction worker in Japan was estimated at 45.3 years old for ordinary workers and 56 for part-time workers in 2024, according to the annual Basic Survey on Wage Structure by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

Meanwhile, in a contrast to the experience in America and indeed most of the Western world, there is a greater propensity for young people to spend in Japan than the baby boomer generation.

This is because the labour shortage means young workers enjoy high wages at the start of their careers while the baby boomers remain stuck in post-Bubble Economy risk aversion.

This is the precise opposite of the situation in America where the baby boomers have accounted for a growing share of household spending helped by the positive real returns on their money market funds, as previously discussed here (see Is Labor Hoarding Masking Job Market Weakness?, 23 October 2024).

Japanese Monetary Policy Outlook

Meanwhile returning to the outlook for Japanese monetary policy, the BoJ’s increased commitment to normalization means that it has not fought the recent pickup in JGB yields to recent highs of 1.60% on the 10-year and 2.89% on the 30-year reached in late March and mid-April respectively.

Indeed the correlation between the US Treasury market and the JGB market has completely broken down this year.

The 10-year Treasury bond yield has declined by 50bp since peaking on 14 January, while the 10-year JGB yield is up 2bp over the same period to 1.26%, though down 33bp from its recent high reached on 27 March.

Will Local Institutions Finally Start Buying Japanese Stocks?

This raises again the core question, from a Japanese equity standpoint, of whether the renewed sell-off in JGBs will finally prompt Japanese domestic institutions to re-allocate out of yen fixed income into Japanese equities for the first time since the end of the Bubble Economy in 1990.

In this respect, the only increase in equity allocation in recent years has been to international equities, which in practice has meant primarily US equities.

The key period for such annual asset allocation decisions is now since such decisions are usually made at the start of the new fiscal year beginning 1 April.

So far there is no sign of such a re-allocation happening.

Indeed this writer heard from one major Japanese life insurer when visiting Tokyo last quarter that its plan was to increase exposure to “private” unlisted alternative assets because they were less “volatile” and so deemed less risky.

This is, in this writer’s view, exactly the wrong thing to do.

It is worth recording again that the Topix has already outperformed the 10-year JGB on a total-return basis by an enormous 349% since mid-November 2012 when the market started to discount the launch of Abenomics and the related commitment to extreme unorthodox monetary policy with the appointment of Haruhiko Kuroda to the BoJ governorship.

We are Skeptical if the BOJ Can Really Keep Raising Interest Rates?

Meanwhile, the risk to the monetary policy normalization narrative is the extent to which inflation has been driven by the weak yen, and the yen now appears to have bottomed having rallied by 12.7% from the low of Y162/US$ reached in early July.

It is also the case that while nominal growth looks healthy, real wage growth shows a much more mixed picture.

Real monthly total cash earnings per employee declined by 1.5% YoY in February and was down 1.3% YoY in the three months to February.